A Year of Firsts and Lasts

Edlene LaFrance remembers her husband, murdered by Mohamed Atta

As promised yesterday, I’m spending this 9/11 weekend dusting off two pieces that I wrote a year apart, but that are inextricably bound. “South Toward Hell” was a snapshot of the streets of New York right after the Twin Towers fell. If you missed it, you can read it here.

Its follow-up, written almost exactly a year later, remains near’n’dear to me. At the end of the first piece, I met Edlene LaFrance, who was awaiting the worst news a wife could ever get: that her husband was one of the victims of the terrorists’ homicidal orgy. Our national tragedy – the one that launched us into a twenty-year war, and that would make air travel a pain in the ass for the rest of our days – became her personal one. Except that her war never ends, and she gets reminded of it each year, once again, on this date.

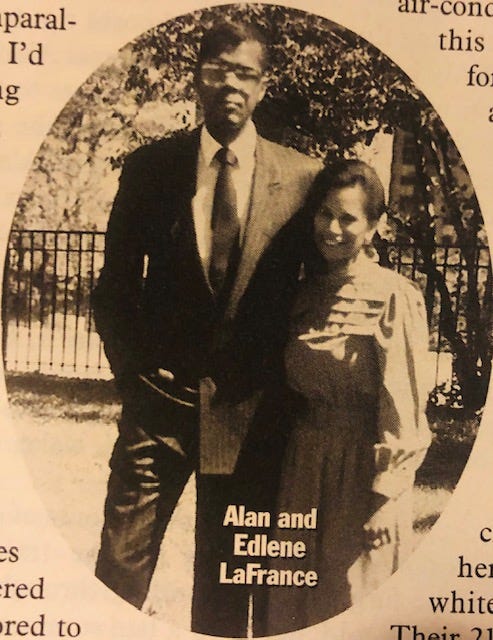

Edlene is no showboat or grief-milker. In fact, she’s precisely the opposite. She never even told her own mother, who was senile when her husband Alan was killed, that her daughter was now a widow. But Edlene was generous enough to grant my request to reenter her life, so that I could detail the changes that took place in hers, even as the rest of the world was reordering itself around us. It feels fitting to rerun it now, I suppose. This year marks the 21st anniversary of 9/11, the same amount of time Edlene was married to Alan. Time, they say, is a healer. But it’s also a pisser.

Bronx, NY

I met Edlene LaFrance on the worst day of her life. Or maybe it was the second worst, or the fifth, there are so many to choose from now. Two days after the Twin Towers fell, her 43-year-old husband, Alan, lay buried at the bottom of one of them. Though the city was awash in acts of unparalleled selflessness, I'd spent that morning thinking selfishly, walking the ash-caked streets of lower Manhattan, trolling for battle-scarred humanity to fill my notebooks before deadline.

On a bum tip, I rushed to the Chelsea Piers, where ambulances full of recovered wounded were rumored to be arriving. When I got there, a bystander scoffed at my naivete. "There aren't any more wounded," he said, letting the thought finish itself. Another reporter suggested the action had moved cross-town to the National Guard Armory on Lexington, and indeed it had. The street outside the building looked like a third-world bazaar. Except instead of merchants peddling trinkets, family members were holding "Missing" posters, begging for whereabouts and clues, as if their loved ones had gone down to the corner for a pack of cigarettes, then had forgotten the way home.

The media were supposedly barred, but I slipped inside the building. In all the chaos, it was about as difficult as crashing Penn Station. Hundreds of family members sat in rows, their bodies racked with tension and slicked with sweat in the un-air-conditioned hall. Amidst this grimness, I scouted for the most approachable faces, which belonged to Edlene, her son Jody, and his wife, Camille. I asked if I could follow their family through this process, and they graciously assented. Edlene clutched a photo of her husband in his white wedding tuxedo. Their 21st anniversary was in two weeks, and on the morning of September 11, for some reason, she'd come close to giving him his biggest present early--a new wedding ring.

We made polite chat over grief counselors' incessant offerings of sandwiches and Sprite. Edlene quipped that she could use some tranquilizers instead. She answered all my questions dutifully, but her eyes kept drifting to the archway at the front of the room. It was there, down a staircase, that 20 people at a time were being taken to scour two lists--the first indicating that their loved one had turned up hospitalized, the second that they'd turned up dead.

When it was the LaFrance family's turn, we went downstairs. A Red Cross volunteer offered to look for Alan's name. Edlene, a portrait of poise a few minutes earlier, simply laid her head down on a table while her son sat beside her, stroking her hair. Alan didn't turn up on the deceased list, but he wasn't on the hospitalized list either. A deductive silence enveloped us--the sound of someone's life coming undone.

A year later, as journalists and grief groupies again jostle for a piece of 9/11, it's tempting to sit back and chortle at excesses and opportunism. God knows the last year has seen enough of them: American Paper Optics issuing "Images of 9-11 in 3-D," the commemorative cigarette lighter with a flame flickering right over a picture of a burning World Trade Center, the "9/11: 24/7" mock-tribute album from drag-queen Tina C. featuring songs like "Stranger on the Stairwell" and "Kleenex to the World."

Still, as we congratulate ourselves on how life goes on in all its wretched excess, there are thousands like Edlene. Her life actually has changed, and will remain that way beyond any news cycle.

I catch up with her at an apartment building that sits next to a noisy highway in the Bronx. A landlord's letter posted in the lobby cautions residents not to let their pets urinate in the stairwell. She welcomes me at the door, and says that she has lost some weight and some hair since we last spoke, but she is just as I remembered: diminutive and dignified, her warm voice accented with a steel that suggests she is being brave by necessity, if not by nature. Her rent is $709 per month, and it seems a bit steep for the two rooms she inhabits. They're the same rooms she lived in with Alan. And in a way, that $709 is what got him killed.

An audio/visual technician, Alan freelanced all over the city--primarily doing conferences at a New York public library and at the Windows on the World restaurant on the 106th floor of the World Trade Center. Edlene could always tell to which job her husband was headed by what he was wearing. If he was off to the library, he'd wear casual clothes. If it was the World Trade Center, he'd put on a black suit. The library gig was more lucrative, but his employer took too long to pay (six to eight weeks).

Though usually Alan just worked nights at the World Trade Center, he sometimes needed money to make rent. So the morning of September 11, he went there to set up a breakfast conference. Edlene can't remember her last words to her husband, but for days after the towers went down, she tricked herself into recalling that he hadn't been wearing his black suit.

From the testimonials of his friends and relatives, it is clear Alan was the kind of guy you'd want to be around. He liked his breakfasts big and greasy at a nearby diner, and he loved to play drums. At his Jehovah's Witness congregation's cookouts, he always assumed the role of grillmaster, perhaps because even at 6'4", he was such a suspect basketball player that friends mockingly called him "Jump Shot." He took his grandmother shopping almost weekly. He liked to work on cars, but not for money. Often, Edlene would gaze out the window at busy Bruckner Boulevard and see a stranded motorist. She'd shoot her husband a help-those-poor-people look. He'd grumble a little, then grab his tools and ride to the rescue.

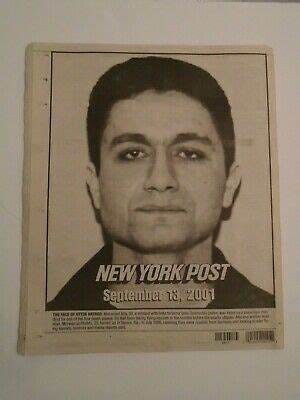

Now, the first face Edlene sees in the morning is Mohamed Atta's. She keeps a New York Post cover photo of the man who killed her husband on the floor next to her bed. Every morning when she wakes up, she steps on his face. It is a small, desperate gesture, but it's the only revenge she'll ever get. When asked why she'd keep a picture of this murderer in her bedroom (she never calls him a "terrorist" or "hijacker," always a "murderer"), she says, "A lot of times when I don't think it's real, I just turn over and there's his face. Then I know it's real.”

It wouldn't seem she'd need any more reminders. Her husband, who had no life insurance, handled the finances, and within the first few weeks after he died--her mind scrambled and her heart literally palpitating--she couldn't even locate her checkbook. Unable to keep track of the bills, she had to get an extension after an eviction notice. Though some charity has found her (Black America Web Relief ended up footing her rent through August), most of the $30,000 or so she's received from victim's assistance funds has gone to offset her son Jody's expenses, since he frequently has to fly back with his family from Chattanooga, Tenn., to help his mom navigate mounds of paperwork and other disasters.

A typical one occurred when Alan's old Volvo had to be retrieved from an impound lot where it was towed from the train station after sitting there for weeks (Alan had the only key). Likewise, her telephone was nearly cut off, but with her nursing job in a "clinic in a bad neighborhood," she has managed to keep it paid up, along with Alan's cellphone account. She doesn't have the cellphone--Alan had it with him when he died--but by keeping the account open, she can still call his messages to hear his voice. "They never found remains," she explains. "It's all we have left of him."

Edlene LaFrance is not a whiner, though she could be forgiven if she were one. She hasn't told her overburdened son that her doctors are worried she has breast cancer. Having switched nursing jobs earlier this year, she has told no one at work besides her boss that she lost her husband on 9/11. Even her own mother, who is senile and who Edlene doesn't wish to traumatize, has no idea her daughter is now a widow. "When she asks where Alan is," Edlene says, "I tell her he's at work.”

I ask her if she blames God for any of this. "Why would I?" she asks, out of conviction or convenience or both, "He didn't do it." She says she's been hitting the Scriptures pretty hard lately--not Job, as you might expect, but all the widows'n'orphans passages. There are a lot more of them than she had noticed before, and she says they present a compelling body of evidence that God won't let her fall through the cracks. So far, she says, He hasn't.

The thing that's changed the most for her is time. She no longer measures it in weeks and months, but in firsts and lasts--the last time she did something with Alan, the first time she must do it without him. She doesn't cry much anymore, but the day before my visit, a light bulb burned out in her hallway. She ended up in a heap on the kitchen floor for 20 minutes. It was a 1,000-hour bulb that Alan had last changed. She has not replaced it.

There are long lists of firsts she is avoiding. She will not go on vacation, and chooses not to go to the movies, since that was Alan's favorite pastime. When she goes to their favorite diner for breakfast, she sits at the counter, since she and Alan used to sit at a booth. She knows she must get over this, and it will be easier to, she reasons, after September 11. Right now, she dreads that date the most. Though she'll be surrounded by extended family, all she really wants to do, she says, "is take some sleeping pills and wake up on September 12th."

After hours of conversation, we set off for the train station on foot, strolling through her neighborhood in a late summer half-light. Another 30 minutes, she says, and she wouldn't be out on these streets. At first, I think she means because they're crime-ridden. But no. "That was the time me and Alan always walked together," she explains. As she says this, I nod understandingly. But I can't understand. Not really. We have all grown rather possessive of September 11, taking it out, reexamining it when it suits us, making it mean what we want it to mean. Edlene doesn't have that luxury. I want to make it easier for her, but that can't be done, so I hold my tongue. She thanks me for listening, and I nod some more, as she puts me on a train that will take me back to my wife and son.

Postscript: Edlene LaFrance, if you can’t tell by now, is a dear woman. So she became one of those subjects that stayed in my life long after I was done writing about her. We used to talk every year on or around 9/11. Now, we talk every two or three. (I just spoke with her yesterday, in fact.) She’s doing well. She remarried a little over a decade ago – she came to my house for lunch shortly thereafter with her new husband, a real gent. And she now lives about a half an hour outside the city. Edlene retired from nursing, even if the forces of COVID didn’t want to let her go. But she’d already done her fair share of taking care of other people. Here’s hoping time keeps mending her the way she once mended others.

Bonus Track: Here’s a young comer you might have heard of, off his 2002 album, The Rising. There were a slew of tunes on that album that touched on what happened to our country on that horrible day, including the title song. But I was always partial to “Lonesome Day,” the video for which was shot in Springsteen’s old stomping grounds of Asbury Park.

Edlene LaFrance's incredible dignity in the face of loss and pain is inspiring in a way that leaves me feeling helpless. There is no way to restore wholeness. Only healing that leaves massive scar tissue. Her strength in carrying on even when giving up might offer respite is something that challenges all of us to live up to her example. God love and keep Edlene.

Today we are once again "reexamining" Sept. 11, since at the moment "it suits us" to do so. And each of us who ponders the events of that day will again engage in "making it mean what we want it to mean". And that meaning will differ for each one of us in some ways, both large and small, depending on how each of us experienced those horrific acts of mass murder and our current memories of them; or now, these two decades+ later, whether we even experienced them in the first place or have any actual memories of them at all. But what the half-light of our memory - be it collective or as individuals - should never cast a shadow upon, or color the meaning of, is the racial and religious arrogancy and darkness in the hearts of a few that then infected many and that ultimately led to the brutal murder of many, many more. And we would do well to remember that this is nothing new in the history of mankind's existence in this world, and that the evil that drives men to such acts - at whatever time, in whatever place and on whatever scale - lives not just in foreign lands, but here at home as well, in the dark hearts of unworthy men.

And if September 11th has any meaning at all, it should at least be that we, as a nation founded on the principles of equality and democracy and the hope of the life that those principles can make possible for all of us - no matter how as yet imperfect our practice of those principles may be...that we will find that it "suits us" to always and unfailingly stand up for those principles, and to stand against those who do not believe in them and who would not allow us to practice them if they could put an end to America's bold and righteous experiment in self-governance, or even to America itself, be they in foreign lands, or right here at home. Especially and particularly, be they right here at home. For failing this, it will be we who are unworthy of the blessings our country is capable of bestowing on us if we stand and deliver on what we know in our hearts to be right.