Are We Cursed, Or Are We The Curse?

And how a badass priest in Haiti turns on the lights while standing in darkness

Editor’s Note: Have a question about your unsightly goiter? Ask your endocrinologist. Have any other questions? Ask Matt at askmattlabash@gmail.com.

Dear Matt,

How about a little Jeremiah: “Oh Lord, why do the wicked prosper?” A rhetorical inquiry, I imagine, but it does indicate how long we've been burdened with the dilemma. Which begs the question: “Are human beings cursed, or are they the curse?”

Susan J.

I must confess, I stole this question from the comments section from a few pieces back. Though since it is my comments section, it’s less like I stole it, more like I relocated it. (Shameless pitch to free riders and non-subscribers: you too can mix it up in every comments section with the similarly enlightened, thoughtful, non-trollish readers who tend to inhabit this place– some of whom aren’t even related to me – by becoming a paid subscriber.) Besides, I am often most attracted to questions that I struggle with myself. The bad thing about being a verbal flasher– also known as a “writer” - is that it encourages you to display your own intellectual/spiritual shortcomings in public. The good thing is that it forces you to know your own mind, assuming there’s anything in it. So I periodically like to tackle the tough ones, as long as they aren’t questions that leave me completely stumped, such as: “How does a bill become a law?” or “What is the pompatus of love, and can it be cleared up with antibiotics?”

But here is the dark truth: humans are both accursed, and we are the curse. Yet we also contain the antidote to what poisons us. Or rather, the light that shines through us (some suspect God is the light source), if we allow it to, can relegate that darkness to an insignificant shadow. As a species, we often create our own misery, but can also remedy it. The book of John tells us that “in this world, you will have trouble.” It’s a prediction that has proved to be stubbornly true: when it comes to troubles, the supply chain never breaks down.

These troubles can seem both inescapable and ever present – the current ones in Ukraine being the most pressing example. As I write this, news just broke that a children’s hospital in Mariupol was bombed by Putin. Such happenings practically invite us to despair. But despair isn’t an answer. It’s just a not-so-easy out. Despair is a natural, paralyzing reaction to seemingly insurmountable difficulty. But it also adopts a tunnel-vision of reality. It doesn’t see around corners, or imagine what can come next. It doesn’t envision how human depravity and cruelty, which know no bounds, can also elicit the very best from people who flick their Bics in the blinding darkness. (See Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky. A month ago, he was a washed-up comedian who, as an iffy national leader, was considered a washed-up comedian. It was thought that he was way out of his depth. Now, he’s doing a passable impression of war-time Winston Churchill.)

Allow me to further illustrate with a couple stories about one of the most dynamic, courageous, badasses that I know.

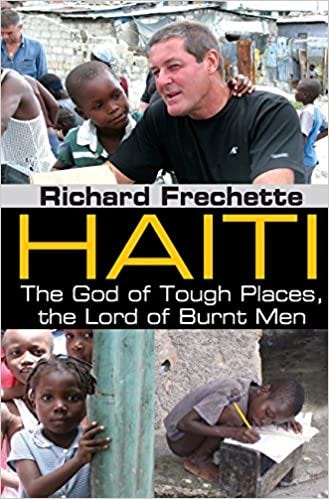

Back in 2010, after an earthquake shook the ground in Haiti so hard that it killed about one out of every 45 Haitians, I went to Port-au-Prince to profile an American priest who was in the thick of things. (I won’t recap too much of it here, as I plan to eventually rerun the piece in its entirety on a week when I’m away.) Father Rick Frechette had come to the land that good fortune forgot decades earlier as a straight-up missionary. But seeing what the people really needed was a doctor, he became one of those, too. He started a hospital, an orphanage, and around 30 street schools. He trucked water to Cité Soleil, one of the most dangerous slums in the world. He negotiated kidnapping releases – kidnapping foreigners having become one of Haiti’s only growth industries. He went nose-to-nose with gun-packing gangsters, often coming back to civilization (if Haiti can be called that, with its crushing poverty and unpredictable violence) with his relieved hostage in tow.

As I shadowed Frechette all over the city, I saw suffering like I’ve never seen before: Women washing themselves in mud puddles. Fresh amputees camped out on the hospital lawn – they were all out of beds - having their children nurse their seeping stumps. Newly-homeless families bedding down between two parked cars so they wouldn’t be run over in the night. Two dogs, which looked like rib cages on sticks, busying themselves around a hole in the wall of a collapsed cathedral. They turned out to be feeding on two quake victims, which had already been consumed down to their skulls.

Even before the earthquake, Frechette and his team went to the Port-au-Prince morgue every Thursday. There, they claimed the unclaimed dead – laying in a literal pile of bodies in an un-air-conditioned room, maggots crawling everywhere – to bury them in cardboard coffins in mass graves in the rolling wastelands of Titanyen. A former Papa Doc Duvalier killing ground, Titanyen’s name translates as “the Fields of Less than Nothing.”

“You’ve heard of Tuesdays With Morrie?” Frechette joked. “This is Thursdays with the Krokmo.” (A Creole pejorative for “undertaker,” which translates as “the death hook,” meaning the show is over.) I went with him to the morgue, the heap of bodies stacked higher than ever - watching his men sometimes pile multiple emaciated dead children into the same cardboard coffin (the quake had them running low on inventory). In order to keep from vomiting, we had to drink rum, rubbing it on our upper lips, while smoking cigarettes, so that the smoke and the alcohol would blot out the sickening smell. Though no smoke or drink could blot out the sight.

As we barreled up a sun-bleached highway along the Caribbean with new tenants to be planted in the Fields of Less Than Nothing, I asked Frechette why he’d pay this kindness to people who would never know the kindness had been paid. He thought in silence for a long while. Then he said he did it because “if the dead are garbage, the living are walking garbage.”

Several nights earlier, a group of us had gone to Harry’s Bar, after Frechette had visited one of his collapsed medical facilities that had killed a couple of his employees. At the bar, he’d fallen into conversation with another missionary, as they swapped dengue fever and malaria stories. “This is what happens when missionaries drink,” he warned.

In the meantime, one of his Haitian gravediggers, named Fred, began to tell me another kind of hairy story. A few years prior, Fred was supposed to bury a little girl. Her mom was riding to the cemetery with him. When they arrived, a Cité Soleil gang greeted them with guns, booted the mother out of Fred’s truck, and fired shots over her head, scaring her off. They kidnapped Fred, but realized – too late – that they’d also just kidnapped a dead girl as well. They hadn’t noticed the coffin in the flatbed, which would make for a sticky ransom scenario.

So they stole Fred’s truck, then turned him loose, telling him to take the dead girl with him. Fred threw her undersized coffin on his back, and carried her all the way back to the cemetery. When I asked Fred why on earth he didn’t just leave the coffin and run, Fred said he couldn’t. He owed it to the mother. At this point, Frechette broke in, saying he later found Fred in the now-collapsed hospital we’d just visited. He was sobbing uncontrollably. When Frechette asked why he couldn’t stop, Fred said, “The thing that bothers me most is that the mother doesn’t know that I fulfilled my pledge to her, and that I buried her child tenderly.” Frechette added, “He knew her love for the kid, and he had to carry her love for her. And he did it. You see why I do these things? In the most horrible situation, an ex-con kidnapped by the most brutal of thieves, stealing a corpse and chasing the mother off with guns. . . . Do you see the goodness that came out of it? It’s unbelievable, isn’t it? It’s unbelievable.”

I have kept in sporadic touch over the years with Father Rick. Even though I’m not Catholic – just a lukewarm Prot – I’ve always found it sound policy to remain friends with people who are wiser than I am. (In my case, this gives me a large pool to choose from.) Frechette is still at it, practicing love among the ruins. His letters to friends and supporters read like a Cormac McCarthy novel, if McCarthy possessed a truly dark imagination. There are always more natural calamities, more violence, more kidnappings, more close calls. But, as he wrote in a group-email not long ago, “It is important to witness the power of faith, and to share the strategies that both free those in literal human bondage, as well as to lift those who have been crushed by tragedy yet again.”

And here is something he wrote to me a few years back. (For some reason he’s never specified, he always writes in lowercase, with next-to-no punctuation, and always in poetic line breaks, even though it’s all prose). This missive came to me after Frechette’s burial truck had been set on fire by an angry mob in the middle of political unrest. Frechette and his colleagues narrowly escaped death, as a local gang leader named Ti Hougan (little voodoo priest) intervened on his behalf, saving their hides, as he blew holes in the gas tanks of several of the motorcycles of the thugs who’d accosted Frechette and his volunteers. Ti Hougan then set their bikes afire.

I asked Frechette how he could deal with all this, and keep dealing. How does he not lose his head or his hope? His reply has always stuck with me:

there are only two kinds of people in this world in spite of a million divisions

religion, colors, nations, economic class, IQ, sexual orientation, etc.

the two kinds of people are

people who care

and people who don’t….

similarly with pain

two main kinds

the pain within you (self-image, shame, depression, the noonday devil, your cancer)

and the pain that comes because you care about someone else

the first is heavy, spirals ever inward, becomes like a black hole, takes all your energy, dreadful

the second is light (it is still pain), spirals outward, has a moon shine, gives you energy and is fulfilling

of course they can mix together

i find living for other people invigorating

i find doing the right thing invigorating

i get very used to all the bad things that can happen

they all create ways you can be more helpful

and therefore more vital and invigorated…

hardship brings fear and pain

but they do not take a dominant place

in someone quite satisfied with a life of caring

the deeper the caring the truer this is…..

where does the energy come from?

caring

and seeing the stranger you would never guess join you in battle (ti hougan)

and knowing the sisters would have been there in a minute to help

rosary beads skyward

pain speaks holy words

the words can get smothered

by self-pity

by fear

by resentment

or you can {allow} the pain to speak

speak to your self-pity, fear, and anger

as you set your mind and heart back to caring

Bonus clip: This might be my favorite deleted scene of all time. It comes from a riveting documentary, Big River Man, about a crazy Slovenian named Martin Strel, who swims down the world’s biggest rivers, even though he’s in his fifties, overweight, and drinks two bottles of wine each day. While the film follows him swimming all the way down the Amazon, this scene depicts his American chase boat navigator, a Walmart employee from Wisconsin. He happens upon a miserable pet sloth, chained up in a dive bar in Brazil. Why the scene was cut, I’ll never understand. It’s about freedom, and second chances, and the kind of caring Father Rick was talking about. Stick around for the 2:30 mark.

Thanks for the humbling story, Matt. And not only because of your expressive talents.

It’s humbling to remember that parts of this world are made somewhat less miserable thanks to the daily, dedicated efforts of those who take care of essential life chores in places too scary for most of us ever to have to see in person, much less year in, year out. And somehow in their souls and/or inner beings find more reward in that work than most would never imagine possible.

God bless Father Rick! When crowns are given in heaven, he will have a multitude!