Don't Leave Me Alone In The Twilight

Saying goodbye to Robbie Robertson, architect of The Band

I’m not one to go crying in my beer every time someone famous kicks. If I did, I’d be drinking a lot of waterlogged beer, since life expectancies haven’t expanded at the same rate that the staggering volume of famous people have, what with all the none-hit wonders, reality-show cement heads, and TikTok nitwits who have spread like a bad rash throughout our land. At the rate we’re going, a decade from now, a “famous” person will die every three minutes, and you’ll have never heard of 97 percent of them.

But last month, while sitting in my writing hole putting the finishing touches on a piece, I caught a hard shot in the throat when news broke that the great Robbie Robertson had passed at the age of 80 after a year-long battle with prostate cancer. It’s hard to say what the bigger shock was: that he was gone, or to see that number attached to his expiration date – 80-years-old. Because I’d come to think of the man, like so much music that he gave us, as not exactly young, but ageless, his songs having rattled around in my head for the better part of my life. Robertson, of course, was the lead guitarist and driving songwriting force of not just a band, but The Band - a name the boys settled on after briefly considering “The Crackers” and “The Honkies.”

Despite their generic handle, The Band made a monumental impact on music in a relatively short period of time. Their first album came out in 1968, and by 1976, they were already packing it in at their farewell concert, which gave us the Martin Scorsese-directed documentary of the same name, The Last Waltz, two years later. But to measure just how large a footprint they left, one need only take the word of the late George Harrison, who called them “the best band in the history of the universe.” No small compliment, coming from a guy who was once in a pretty fair band himself.

The musically-nimble Beatle knew what anyone with ears to hear could readily spot: that this remarkable ensemble served up a strangeness that was utterly familiar. Much like the British Invasion played our blues back to us, making it new, The Band – four Canadians (Robertson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson) and a yowling, spitfire drummer who grew up on a cotton farm in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas (Levon Helm), took a raw-ingredients pinch from every slot of our rootsy spice rack: from delta blues to Staple-Singers-style gospel to high-lonesome country to Motor-City soul to Appalachian front-porch string bands to Sacred Harp singing to Louisiana swamp rock to a good ten other influences I’ve forgotten or failed to name. They dumped it all in the stockpot, blended it, and cooked up their own unwritten recipe (none of them besides their organ-genius Garth - who honed his chops playing his uncle’s funeral parlor, and who used to charge the rest of The Band for music lessons in their early days - could even read music). They made us feel like we were hearing old songs that we’d temporarily forgotten, sung by longtime friends we’d just met, helping us to recall what makes us, us. Or, as Bruce Springsteen once put it: “Here come all these voices that sound like you’ve never heard them before, and they’ve always been there forever and ever.” At their best, The Band played something like ancient hymns that don’t change shape with time, but reverberate throughout it. Some say that the best writing reminds us of what we already know, but haven’t yet articulated to ourselves. That was The Band in a nut. Except they didn’t just articulate words. They set America to music, the purest language that exists. Music being the world where words alone peter out, and something otherworldly takes over.

I had lots of company, then, in feeling the Robertson void. Scorsese, who started collaborating with Robertson on The Last Waltz - which many, including me, regard as the greatest concert documentary of all-time - and who has continued to collaborate with him ever since (Robertson having scored or served as a music supervisor on many of Scorsese’s films, from Raging Bull to Gangs of New York to the soon-to-be-released Killers of the Flower Moon), issued this statement:

Long before we ever met, his music played a central role in my life—me and millions and millions of other people all over this world. The Band’s music, and Robbie’s own later solo music, seemed to come from the deepest place at the heart of this continent, its traditions and tragedies and joy. It goes without saying that he was a giant, that his effect on the art form was profound and lasting. There’s never enough time with anyone you love. And I loved Robbie.

Bob Dylan probably summed it up even better in his terse disbelief: “This is shocking news. Robbie was a lifelong friend. His passing leaves a vacancy in the world.”

Dylan and Scorsese and George Harrison weren’t alone in their assessment of Robertson’s musical magnitude, along with The Band’s, when all of them were still alive. (Garth Hudson, now 86, is the last man standing.) Guitar god Eric Clapton reportedly felt prompted to disband Cream after hearing The Band’s first album, Music From Big Pink. His own music, and the clamorous psychedelia accompanying it, now seeming mannered and soulless compared to The Band’s greasy-skillet collaborative style: trading off vocals in the same song, singing with each other and to each other, swapping instruments (all of them were multi-instrumentalists), containing almost no show-offy guitar solos, which were all the rage at the time. Decades later, Clapton admitted how frustrating it was that The Band didn’t take him into their lineup, which he would’ve joined in a second if invited. When Clapton stopped by their crash pad near Woodstock and asked to jam, Robertson candidly admitted that they don’t jam. They play songs. Clapton remained a friend – he inducted them into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1994. But they didn’t need Clapton’s services, since Robertson, their primary songwriter, already had lead guitar pretty well nailed. He was an expert in close knifework, stabbing precise licks into a song to service it, instead of smothering it under a pillow of exhibitionistic virtuosity, which he was certainly capable of. (He’ s ranked 59th on Rolling Stone’s list of best guitarists.) But Robertson wielded a scalpel, not an axe.

Before The Band became “The Band,” when they still served as Bob Dylan’s backing band in the years when he first went electric (they were then still loosely known as The Hawks, since they had previously backed rockabilly force-of-nature Ronnie Hawkins before Dylan), Dylan told Keith Richards at a party after Dylan’s show that The Hawks were the greatest band in the world. To which Richards asked, “What about us?” Dylan brutally informed Keith that the Rolling Stones were the best philosophers, but The Hawks were the best band.

The Band influenced everyone during their heyday from the Grateful Dead to Elton John, who came around, along with his collaborator/lyricist Bernie Taupin, to hand The Band the first acetate of John’s 1970 album, Tumbleweed Connection, as a goodwill gesture. They were hoping the boys didn’t misinterpret their “inspiration” as Elton/Taupin having ripped them off. A year later came Elton’s Madman Across The Water album, featuring the song, “Levon,” which some accounts have it was inspired by Taupin’s fascination with The Band’s famous, and famously feisty, vocalist/drummer Levon Helm. (Taken by throat cancer in 2012.) The opening lines of that lovely song are Levon wears his war wound like a crown/He calls his child Jesus/'Cause he likes the name. The only similarity to Levon Helm was the title itself. Taupin, echoing his song, must’ve just liked the name. Still, as Robbie Robertson wrote in his engaging 2016 memoir, Testimony, instead of being flattered by a tribute from one of rock’n’roll’s greatest lyricists, it bugged the hell out of Levon. The borderline sacrilegious Christian verbiage in the song prompting Levon to offer, “Englishmen shouldn’t fuck with Americanisms.”

The list of rootsy, more modern bands that The Band has inspired in what is now known as the grab-bag “Americana” genre ( a genre some suggests The Band essentially launched), is so long that it’d be quicker to list the ones who haven’t been influenced by them. Everyone from Wilco to Gillian Welch to Old Crow Medicine Show to My Morning Jacket has paid tribute to them. Counting Crows and Drive-By Truckers have even written songs about their dead members. (“If I Could Give All My Love (Richard Manuel is Dead)” and “Danko Manuel,” respectively.) Rick Danko, the Band’s bassist/vocalist who sang the yearning, desperate harmonies and leads that helped crystallize their sound (Danko, I should disclose, is one of my favorite vocalists), died prematurely of heart failure in his sleep in 1999 at age 55, more than likely from years of hard living, drug abuse, and creeping obesity, after once serving as the closest thing The Band had to a pinup boy. Richard Manuel, their jittery-voiced vocalist, who also played their piano man (though he’d taught himself to play drums – he was drummer extraordinaire Levon Helm’s favorite drummer, in fact), and who could sing both higher and lower than anyone else in The Band, died a little less peacefully. In 1986, after a dispiriting show, he hanged himself with a belt buckle strapped around his neck while suspending himself from a shower rod in a bad motel in Florida. He was only 42. Danko sang Manuel home beautifully at his memorial service, with Bob Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released” (which The Band themselves had recorded). On his first solo album, released a year after Manuel’s suicide, Robbie Robertson paid tribute to his old bandmate with a heartbreaker of a tune called “Fallen Angel,” (featuring Peter Gabriel on backing vocals, and Robertson’s former Band mate Garth Hudson on keyboards.) A song that haunted me as a teenager, and still does so now:

In my dream the pipes were playing

In my dream I lost a friend

Come down Gabriel, and blow your horn

‘Cause someday we will meet again

Most endings are sad ones, of course. But the beginnings of The Band couldn’t have been more charmed/picaresque. Robertson was born the only child of a Cayuga and Mohawk mother who was raised in the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve west of Toronto. It was there, in his frequent visits, where music first worked its voodoo on him. He sat in the kitchen of relatives, listening to them play guitar, with mandolins and fiddles and Iroquois water drums sometimes sneaking in. “It rang my bell,” he wrote in Testimony, “the sound, the rhythm, the fingers on the strings, the voices blending together in unison and then slipping into harmonies. My uncles and cousins were so lost in the music that it mesmerized me.” Likewise, Robertson was enchanted when sitting in front of the village elder, banging his walking stick as he uncorked epic tales. “It sent a charge right through me. The cadence of his voice, the power, the violence, the righteousness. I only hoped someday I could tell stories like that.”

His parents split when he was an adolescent, his mother breaking it to him late that his real father was actually a Jewish gambler, killed in a hit-and-run accident before Robertson ever met him. Though he did take up with his biological father’s brothers after the fact, and might’ve become a racketeer if not for the pull of music. Robbie’s mobbed-up Uncle Natie, put on trial for possessing stolen diamonds, had a reputation as the Canadian Meyer Lansky.

He formed a band in his teens, The Suedes, and while playing a club in Toronto, Robertson caught the notice of American rockabilly force-of-nature Ronnie Hawkins, who often gigged in Canada as America’s brightest lights – like The Killer, Jerry Lee Lewis - sometimes cast shadows on his shine back home. Hawkins persuaded Robertson to move to Arkansas – Hawkins’s HQ – to apprentice in his backing band, The Hawks. A 15-year-old Robertson recognized The Hand of Fate when he saw it, and sold his prized ’58 Fender Stratocaster to scratch up bus fare to get to the Land of Plenty, a place where Delta bluesmen and other early rock’n’roll legends stalked the earth. When he got off the bus in a sweaty overcoat, looking like a refugee, he nearly got high off the scent of fried food and Ozark pines. He’d arrived at the Center of The Universe, the American southland of fantasy and literature and song. As he once told Levon, “I’d hear something at night and not know whether it was an animal, a harmonica, or a train, but it sounded like music to me.”

The Hawk, as Ronnie was called, and as Robbie tells it, “prowled the stage like a caged animal…..singing like he was driving a mule train, and when he did the Hawks would settle into a slippery, swift locomotion behind his vocal.” At the center of it all was a drummer who “seemed to glow in the dark,” as Robertson once told an interviewer. “Teeth gleaming, laughing,” Robbie wrote in his memoir, “whole body shaking, drumsticks twirling, pushing those red sparkle drums with a hawk painted on the bass drum like a white tornado. It was the first time I saw Levon Helm, and I’d never seen anything like it.”

Levon was only three years Robbie’s senior, but Robertson repeatedly referred to him throughout the decades, even up until the end after there had been much acrimony (more on that later), as the older brother he never had. Levon showed Robbie the fundamentals of rhythm and southernness. He threatened to bite the nose off an irate potential attacker who cornered Robbie at a drive-in for allegedly sneaking around with his girlfriend. He introduced Robbie to his very country family, whose sister used to play washtub bass in an early band she’d formed with Levon called The Jungle Bush Beaters, while Levon’s dad broke wind in front of company, trying to divert blame to his wife, accusing her of making a “sound like you stepped on a big ol’ bullfrog.” While Robbie obsessively and ferociously perfected his craft, switching from bass – where Ronnie initially stationed him – back to lead guitar, outplaying seasoned musicians twice his age, The Hawk also educated him in life skills. He not only said of Robertson, in Levon’s telling, “This cat’s a genius.” But he told Robbie, “Son, you got the job. Stick with us, and you’ll get more nookie than you care to eat.”

One by one, as Ronnie Hawkins’s old band kept falling away, he added fresh young Canadians, who learned to play, as Robbie put it, “with a sweet kind of violence…….hard and tough and rugged and fast, but tight.” Robertson himself trying to find a sound that “was like screaming at the sky.” For being a fairly middling talent as the headliner, Hawkins still deserved credit for assembling one of the best bands ever created:

Here came young Richard Manuel, nicknamed “The Beak” for his prodigious avian-like nose, who already had too much of a taste for the substances that would later help do him in, but who sang like a blues-tinted angel. Here came 18-year-old Rick Danko, a butcher’s apprentice from Ontario. He hailed from a musical family and made his debut on four-string tenor banjo in front of his first-grade classmates. When not chopping meat, he played in a polka band. And Levon had to straighten him out as a member of his rhythm section, since Danko used to play bass like he was skipping over ice. “Either you feel it or you don’t,” Levon scolded. “Let’s not waste one another’s time.” But man, did Danko end up feeling it, and making everyone else feel it, too. Not just with his bass, but with his soaring vocals - sweet melancholia incarnate. (Music interlude: here’s one of my favorite Danko leads from their latter Band days, a song written by Robertson just to showcase Danko, “It Makes No Difference,” in which Robertson’s guitar and Garth’s sax echo his lamentation, with Levon and Manuel lending gorgeous harmony on the refrain):

And then of course, came the musical wizard Garth, straight from boot camp in his uncle’s funeral parlor. A man who ended up rigging his Lowrey organ to bend the notes as if it were a horn or guitar. Garth was someone who could do unpredictable things, like making funk Clavinet fashionable on Band tunes like “Up On Cripple Creek.” In this beautiful clip of that song from the 2019 documentary, Once Were Brothers, the track is talked over somewhat by the likes of Clapton and Taj Mahal and Scorsese and Springsteen, the latter of whom rightly said, “Not only did they have the incredible writing – Robbie’s writing – but they had three of the greatest white singers in rock history. {Danko, Manuel, and Levon, who shared lead-singing duties, but who sang together even more wondrously.} To have any one of those guys would be the foundation for a great band, to have three of them in one group, that was just loaded for bear.”

Garth was a gold-plated eccentric in other ways, as Robertson – always The Band’s unofficial narrator, like the Indian elders who captured his imagination - told us. Garth was incapable of sweating. He’d buy orange juice, but would wait for days to drink it, waiting for the pulp to settle on the bottom. He was a stone-cold narcoleptic, able to zonk out even during the most critical conversations.

The Hawks ended up gigging all over the place, getting into high adventure. There they were in Dallas, playing a club in which the roof had burned off in a fire, and which boasted a one-armed stripper. Its owner turned out to be Jack Ruby. There they were, eating with one of their blues heroes, Sonny Boy Williamson, at a soul-food dive in Helena after spotting Williamson walking down the street. Sonny bragged to them that he’d illegitimately fathered Little Walter and Little Junior Parker, before cops broke in and chased them out of town for “eatin’ with n-ggers.” There they were back in Canada, at a hotel after-party attended by Bo Diddley, who was trying to pick off Robertson’s romantic interest by singing her impromptu songs:

When this young man’s gone

And Bo Diddley moves in

Patricia gonna know

Real loving ain’t no sin

It was the kind of education they don’t offer at university.

But the Hawks outgrew The Hawk, wishing to musically expand, and to shuck the rockabilly straitjacket. Likewise, there were personal differences, Ronnie being a bit of a despot, forbidding them from smoking weed (this was, after all, the sixties), and fining them if they brought their girlfriends to the clubs, since it could cut down on the number of eligible females who might buy tickets to the show. After parting ways with The Hawk, they had some lean times. Their food regimen typically included shoplifting bologna. And at one point, badly needing scratch, Levon and Robbie actually planned to stick up an illegal high-stakes poker game outside Fayetteville, going so far as to procure ski masks, guns, and a sack to stash the loot. But when they drove to the site where a tipster told them the game would be going down, nobody was there. Thus ending their life of crime before it began. Except for when Robbie would later steal all The Band’s publishing rights. (Only kidding Robertson fans – just my shameless head-nod to Levon partisans.)

After blowing into New York, Robertson was introduced by bluesman John Hammond Jr. to a young Bob Dylan, who’d already made a name. Dylan was going electric, and needed a guitar player. Dylan was seriously impressed by Robbie’s abilities, once saying of him: “Robbie Robertson is the only mathematical guitar genius I’ve ever run into who does not offend my intestinal nervousness with his rearguard sound.” He not only hired Robertson, but took his suggestions to fill out his backing band, first with Levon on drums, then the rest of the fellas, even if some were less than enthused with the arrangement. Richard Manuel initially derided the folkie Dylan as “a strummer.” But together they toured, getting booed all over the world by irate folkies, miffed that Dylan was changing his sacred sound. Audience members cursed the future Band, threw fruit, even once knocked one of Dylan’s other band members off his stool. “Looks like the attack of the beatniks around here!” Dylan once yelled to Levon during a particularly hairy episode.

Dylan would just tell his band “play it fucking loud” when hecklers wouldn’t pipe down, unperturbed and utterly confident in his new direction. The rest of the band wasn’t always so unflappable. Sick of getting booed and cleaning tomatoes off his drum kit, Levon folded up shop, briefly going to work on an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico.

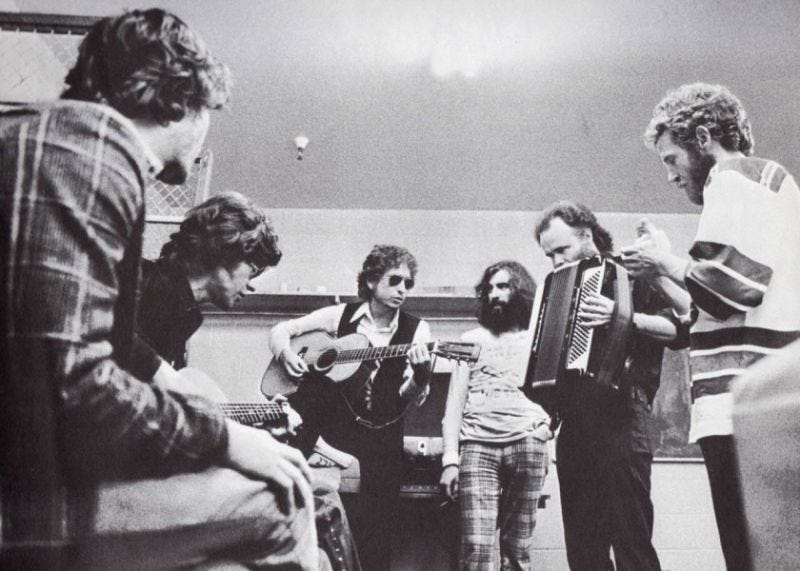

But in 1966, while taking a break from his world tour, Dylan was injured in a motorcycle accident, perhaps milking it, some suggest, to get out of obligations, and back to whatever made him hear music. While he was recovering throughout 1967, Dylan’s manager invited the band to lay up near Dylan on retainer – a sort of hole-in-the-wall-gang respite after they’d spent years on the road. Around then, The Band as we’ve come to know them was truly born. Danko, Manuel, and Garth rented an ugly asbestos-laden pink-siding house in West Saugerties, New York (hence, “Big Pink”), and rigged up recording equipment in the basement. Robertson, already married and living in a nearby abode, would head over there every day, as would Dylan. Once Dylan and The Band were really cooking - the latter on their own stuff, as well - Levon ended up coming back at his bandmates’ pleading, leaving clock-punching work behind. They’d all go to work in Big Pink, instead. Nominally, so that Dylan could pump out songs that he’d send off to other famous artists to sing, while staying off the road, and out of the grind. But those carefree, no-pressure sessions yielded more music in a short period than just about any other. (They recorded over 100 songs together that ended up becoming various iterations of The Basement Tapes.)

Dylan then, like now, had an encyclopedic knowledge of traditionals. So they might lay down an old prison work song, like “Ain’t No More Cane.” (One of my personal favorites from The Basement Tapes.)

But plenty of new material was cranked out. After a fast game of checkers, then having a coffee and a smoke, Dylan would square up behind his typewriter and start clacking out lyrics like The Muse’s own secretary. Seriously in the zone, he might bang out the words to “Tears of Rage,” hand it to Richard Manuel, and say, “See if you can do something with this.” Manuel, not yet debilitated by the drugs and alcohol that would later ravage him (which saw him write no songs after The Band’s first couple years), delivered. The clubhouse atmosphere, with no distractions, spurred creativity. “Songs poured out of Bob and we tore through them,” Robertson wrote. “If lightning struck and you weren’t around, the show went on without you. I had to run a couple of errands before the stores closed, and when I got back, they had recorded ‘Yea! Heavy and a Bottle of Bread” and “Million Dollar Bash.”

More importantly for The Band, which was not yet even called such, it opened up their own writing, particularly Robbie’s. They started knocking out their own songs on the side, and found their sound, playing together in a circle, that would leave their mark on the world. They played less like a band, more like a band of brothers, even if no one was related. In the early days, even when they’d go record their albums at pricier digs, they’d buck engineers trying to stick them in isolation behind sound baffles and gobos to prevent spill-leakage into each other’s mics.

As Robbie complained to their producer John Simon – who was practically a sixth member of The Band on the first two landmark albums: “We can’t make music with an isolated setup. We have to see one another. We have to read one another’s signals. That’s how we play – to each other.” Danko added, “I can’t sing with Richard if I can’t see his mouth moving.” Levon chimed in: “This ain’t worth a damn. I can’t feel where to play fills, and it sounds like shit in these earphones.” They therefore reverted to their preferred studio setup, and feeling their pain, Simon actually retrieved low-grade mics that only pick up what’s right in front of them, minimizing sound-bleed, so they could feed off each other.

And feed they did, the vocalists (Manuel, Danko, and Levon), biting into songs like a three-headed Cerberus, except instead of guarding the gates of the underworld, like the mythical creature, it sounded like they were baying members of God’s own Angel Band. The harmonies not always perfect harmonies – Robertson once suggested that with their lack of formal musical training (aside from Garth), they were playing what they could hit, and it just happened to sound good. But they were perfect in their imperfection. They achieved unity in distinction - kind of like the Staple Singers, who The Band idolized so much, that they owned albums even the Staples themselves didn’t have. Bernie Taupin summed up The Band’s sound nicely in a short, captivating documentary from the Classic Albums series: “They were doing things with harmonies that it almost didn’t feel like they needed to blend octaves. You felt they just sang in unison and their voices were so distinct that they just automatically went into the right place.”

Robertson himself distilled the formula in Testimony:

We were a real band. Everybody played a major role in our balance of musicianship. We weren’t a group with a cute lead singer who liked to take his shirt off, and his guitar man, who also liked being shirtless on occasion. In many bands the other players in the group remained in the shadows; they knew who the stars were. There was nothing wrong with that, but we were holding a different hand – like five-card stud. Nothing wild. Everything faceup.

This is never more evident than on The Band song everyone knows, “The Weight” (which amateurs sometimes call “Take the Load off Fanny”). It’s a song everyone should know, as it’s one of the greatest ever written. From the opening Curtis-Mayfield-like licks of Robbie’s guitar, to Levon wearily singing about pulling into Nazareth, feeling ‘bout half past dead, it is positively Biblical. With the one-and-two line sketches of put-upon everyday saints who are loaded up with other people’s burdens, they were mostly based off characters the boys knew back in Arkansas during their Hawks apprenticeship: old Luke waiting on the Judgment Day…..Carmen and the Devil walking side by side…..Crazy Chester catching up with you in the fog, promising to “fix your rack, if you’ll take Jack my dog.” Even John Simon, who produced it, didn’t have any idea what most of it meant. He just knew it sounded like the whole ball of wax – anything and everything, with all those glorious staggered echoes of “and…..and….and… you put the load……you put the load right on me…..”

It’s the song in which Robbie arrived as a full-fledged, no-joke songwriter. (When Bob Dylan first heard it, he said, “This is fantastic. Who wrote that song?”) Robbie was pulling from every influence in his orbit, as he once explained to the Wall Street Journal. He was inspired by everything from a bookshop recommended to him by the poet Gregory Corso when they were both living at the Chelsea Hotel (the shop owned by a woman named Fanny Steloff); to the screenplays he bought there by the likes of Luis Bunuel; to picking up his old 1951 Martin D-28 acoustic guitar to write the song, and seeing a label inside that said “Nazareth, Pennsylvania” where it was manufactured; to “Crazy Chester,” a character he spied in a wheelchair back in Fayetteville, “who was kind of nuts – he’d roll into the town square, and when the girls went by, he’d call out ‘hoocha, baby, hoocha.” And on and on it went. Robbie knocking out his stitched-together finds on his portable typewriter, just like he’d seen Dylan do: “There was no magic to this process. It was just that Bob knew how to type. He had taken typing in school.”

In other words, Robbie Robertson was a 360-degree observer of all that unfolded around him. He’d have made a good journalist, if he’d had less talent.

Though I am a big enough Band fan to want to believe they did no wrong, I am honest enough to admit that they only made two truly great albums. Their first, 1968’s Music From Big Pink, and their second, 1969’s The Band, commonly known as The Brown Album for the cover’s general all-around brownness. There are so many fine songs on these, this could become a 20,000 word-piece deep-diving into all of them, which I have no interest in writing, and you’d have even less in reading. Though if you don’t know their music, on your own time, I highly recommend hitting their cover of “Long Black Veil”; Richard Manuel’s gorgeous “Lonesome Suzie”; the populist anthem that actual populists (the kind with callouses on their hands) should be attuned to, “King Harvest (Will Surely Come)”; the best old-man song of all-time, “Rockin’ Chair”; their satisfying rocker “Look Out Cleveland”; a tune in which Danko sounds as good as he ever has, “The Unfaithful Servant”; and Levon’s signature song, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” (no link, because more on that later). That’s only for starters, of course.

But after those first two albums, everything else set in. Fame, hangers-on, drugs, the usual rock’n’roll dysfunction and dissolution. It affected the music. Nobody put it more ruthlessly than Greil Marcus in his ‘70s era classic, Mystery Train:

{Quoting Robertson}: ‘You see – instead of throwing a knapsack over your back and getting out on the highway, to learn about life, we were able to do it together. We were protected by one another. We were secured by one another.’ {End of Robertson quote.}Those are fine words. They tell us that The Band sought in America what they found among themselves: that their music and their stories were not only a version of America, but a reflection of their own unity. All those years on the road had given them their values; in a sense, community was only a projection of comradeship. The group was its own joint-stock world, but it could not survive the honest demands of the greater joint-stock world that was the country itself. Every song on the first two albums had been written before The Band had played a single show in public; once they began to tour, the group, as men who contributed what was special about themselves to something bigger than any of them, began to fall apart. Richard Manuel never wrote another song; the singers stopped calling out to one another across the verses; the uncanny sense of timing that had made The Band’s early music move disappeared altogether. As the Band stepped back from their audience, you could feel the friendship go out of their sound.

I don’t entirely agree with Marcus. The Band being The Band, there were still pockets of beauty all along the way. For their Rock Of Ages live album, recorded in New York’s Academy of Music on New Year’s Eve in ’71, and released in ’72, Robertson turned to New Orleans legend Allen Toussaint to compose the brass charts, and that album contains some of their finest performances. If you don’t believe me, see Levon banging out Motown songwriters’ Holland/Dozier/Holland’s “Baby, Don’t You Do It” (popularized by Marvin Gaye – the only song ever sung by Marvin Gaye that I like better by a cover band) and the Four Tops’s “Loving You Is Sweeter Than Ever” (co-written by Stevie Wonder), featuring Danko, both soulful and buoyant, with a killer echo by Levon. But there were other gems throughout: “The Shape I’m In” off of 1970’s Stage Fright, the cover of Dylan’s “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” done much better than Dylan ever did it, off of 1971’s Cahoots. “Ophelia” and “Acadian Driftwood” and the afore-linked-to “It Makes No Difference,” off of 1975’s Northern Lights, Southern Cross. Manuel, Robertson, and Danko (the last of whom was sawing off fiddle notes and stomping the floor for percussion) playing “Old Time Religion” off-stage in The Last Waltz. Which is as good as music gets.

And then there was “Twilight”– not the crap reggae version The Band released in the seventies, but a song sketch released on their 2005 box set, A Musical History. While Levon, especially in his latter years, liked to denigrate Robbie’s singing abilities, saying sometimes they even turned his mic off so he wouldn’t foul up the magic (comparing Robbie to his bandmates, vocally, is unfair, since virtually nobody could sing as well as Levon and the other two members of their holy trinity), Robbie could still croak out a tune, in a smoky Leonard-Cohen style. As he proved not just on some of his highly-acclaimed solo albums, but on this version. It’s just Robbie on piano begging not to be left alone in the twilight, since twilight is the loneliest time of day. It’s probably my favorite Robertson vocal in his entire catalogue, which, as he told writer Barney Hoskyns, was a throwaway he didn’t even remember singing for the fellas. Used to casting his songs to other people while in The Band, he said, “When they played me that, I thought, ‘I don’t remember this at all.’” Such is the beauty of having talent to spare. Some of your least memorable moments can become the ones that still move people decades down the line.

All that said, Greil Marcus was generally correct. After The Band’s first two albums, it was a fast downhill slide. As even Levon acknowledged in the 2010 documentary about him, Ain’t In It For My Health, relaying to the actor, Billy Bob Thornton: “You know, it was obviously a goddamn screwjob. The credits and the money and everything was all screwed up. And the band wasn’t together but another three years…… It lasted about five years. Took that long, but hell, it was over after that second record. {The Brown Album}.”

Now comes the point in any Band appreciation where the writer usually writes about The Band civil war, and inevitably takes sides - usually Levon’s, the more romantic figure as the genuine real-deal southerner, his Rebel Yell heard in every syllable he sang, whereas Robertson, even if he was the brains behind the operation, was often seen as more of a cool operator, culturally appropriating America and Levon’s neck of it, his musical greatness sometimes feeling once removed in the reckonings.

The who-was-at-fault-for-The -Band-coming-apart question goes back about as far as the Ford administration. Levon himself did plenty to fuel it over the years. Especially when in his 1993 book, This Wheel’s On Fire, he often tore the bark off Robbie, as they say in Turkey Scratch. Condemning Robbie for everything from: not showing up to deliver Richard Manuel’s eulogy, to walking off with song credits for songs they all collaborated on (publishing being the gift that keeps giving, even after the music has stopped), to sucking up to Hollywood, to being a weenie by taking The Band off the road prematurely, to having secretive meetings with The Band’s lawyers (Levon wrote that by the time he arrived, “I always had the feeling the real meeting had started an hour earlier”), to Robbie preening like a peacock in The Last Waltz, making sure his neck muscles were tensed just right for the camera as he sang into a microphone that was turned off.

There were plenty more insults. No offense, real or imagined, was too small to escape mention. Levon, at one point, disavowed the book, claiming much of it was sensationalist shit-stirring by his ghostwriter. But nobody really bought that, as he rarely stopped disparaging Robertson when the latter’s name came up in the years to follow.

For Robbie’s part, he rarely returned fire, seeming nearly embarrassed that someone he’d held in such high regard kept sniping at him. Maybe it’s because, some would suggest, the victor doesn’t need to snipe when he walked off with the spoils (i.e., most of the songwriting credits). But Robertson made it abundantly clear that The Band came apart because he found himself in a group with three guys who’d become heroin addicts (Levon, Manuel, and Danko). Robertson was no babe in the woods when it came to drugs himself – it was after all, the seventies (a backroom at the celebrity-heavy Last Waltz concert, set up by legendary promoter Bill Graham, contained plastic noses on the wall, mirrors on which to cut coke, and a soundtrack of loud sniffing). But Robertson had become paranoid that one of his bandmates would die on the road, with plenty of recent precedent to suggest it was a strong possibility, as many friends of his, like Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix, had been dropping left and right.

Richard Manuel of course, later did die on the road, even if it came by hanging from a shower rod, not from a heroin overdose. Levon, in his book, soft-pedaled the substance abuse that plagued The Band. But Robertson wrote of this chapter that Manuel had taken to walking around with a bottle of Grand Marnier or Drambuie all the time, claiming it helped lubricate his throat. His drug use at one point was so bad that his plan to kick heroin was to instead shoot cocaine. A plan that didn’t work out so well. When his bandmates checked up on him one day, he jumped up to smack the wall with his open hand, complaining about the “goddamn bugs everywhere.” When Robertson asked him what the marks were all over his wall, he said that’s where he had to burn (the imaginary) bugs that were crawling around. “Seeing him in the midst of this madness brought tears to my eyes,” Robbie wrote of Manuel, who was the bandmate that perhaps all the other bandmates loved most.

Their lives had become a mad blur of havoc and pile-ups, sometimes literally, as the more chemically dependent bandmates totaled cars regularly, Manuel once flipping Robertson’s wife in one. (Danko once broke his neck and back in another car crash.) By the time they left their isolation chambers in rural New York and moved to Malibu, life had grown so decadent, that one day when Robertson visited Danko’s house on the beach, Danko asked him to come down and check out a curiosity which he’d seen from an upstairs window. When they went down to spy the unidentified object that had seemed to wash in with the tide, it was none other than The Who’s Keith Moon in a Nazi uniform, totally passed out with waves lapping over him. Nobody seemed to think it much out of the norm. (Moon died of a drug overdose a few years later.)

Throughout this rather lengthy period of The Band’s history, Robertson mostly kept everything together, even if his bandmates, at times, seemed only half-interested. As Greil Marcus wrote, “In order to save the group, Robbie took it over. He took it over as lyricist, manager, strategist, savant, visionary, and spokesman…….And yet, because the group was no longer truly whole, Robbie could not really draw on it; since his links to the country and to his audience were no longer strong, he could no longer see the country or his audience clearly.”

As Rolling Stone’s Rob Sheffield recounted in his appreciation of Robertson, quoting Robertson from an old RS profile on Levon: “I wrote songs before I ever met Levon. I’m sorry, I just worked harder than anybody else. Somebody has to lead the charge, somebody has to draw the map. The guys were responsible for the arrangements, but that’s what being a band is, that’s your fucking job.”

Robertson has repeatedly made it clear over the years, often to the consternation of Levon partisans, that he took the bulk of the songwriting credits because he wrote the lion’s share of the songs. A prospect that even Levon’s longtime collaborator on his solo albums, Larry Campbell, seems to think is a likely scenario. While Campbell loved Levon, he told American Songwriter, shortly after Levon died:

The thing Levon would do, once he got into a frame of mind about something, it was a logic-free zone. There was no changin’ his mind…….{and} I was not in a position to try and make him think otherwise about his experience. My take on it was always that I’m sure there’s plenty of legitimacy to what Levon was bitter about, but that he’s missing something, too; that things could have been different, had he approached the situation differently - that whatever inequity he felt with Robbie, he had some responsibility for that, too…..Don’t know the facts. All I know is Levon’s side of it…..What I can tell you is I’ve written a few songs with Levon, and writing with Levon, my experience was, he wasn’t gonna do any labor where writing a song is concerned.

Indeed, while Levon and what was left of The Band members (minus Robertson) toured and cranked out a few mediocre albums in the eighties and nineties, limping along until Danko died in ’99, Levon released two really fine albums as a solo artist in the five years before he died. (Dirt Farmer and Electric Dirt respectively.) Both won Grammys. But between the 25 songs on those two albums, Levon is only credited with co-writing one of them.

When I asked my old friend, a fellow Band enthusiast, and one of the finest music writers of my generation, Eddie Dean, to send some late-night, wine-soaked observations on the subject, he obliged. Usually a Levon sentimentalist, he dashed off some candid riffs:

The thing about Levon’s drumming is that it is an all-night blues shuffle from the jukes of the cotton fields, unobtrusive, and non-histrionic, only pulse……..which also stems from the backbeat of New Orleans drummers like Earl Palmer (whose memoir is called Backbeat). But it also contains elements of the more aggressively propulsive beat of Chicago blues drummers like Sam Lay who was on a lot of Howlin’ Wolf records with guitarist Hubert Sumlin who had influence on Robbie’s economical, almost back alley, razor-blade guitar (where each stabbing note can maybe kill, if need be.) That said, Richard Manuel took over on drums for “Rag Mama Rag,” which showed Levon’s backbeat could be replaced when necessary, and Levon could play a mean mandolin as well. The only thing that could not be replicated was Robbie’s songwriting, which came out of a documentarian outsider seeing Sonny Boy Williamson spit blood for his craft. {Once when seeing Sonny Boy play, Robertson went up to the stage afterwards, and looked into what he thought was a spittoon, but in which Williamson spit blood while playing harmonica.}…..The holy mystery unanswered? How did the kid from Toronto on the endless dirtbag road with Ronnie Hawkins playing “Who Do You Love,” within five years, {is writing} sacred texts like “King Harvest/Across The Great Divide/Stage Fright,” etc…….The whole thing about Robbie vs. Levon misses the point. Robbie went with coke, and Levon with heroin. ‘Nuff said……..The deal is symbiotic, The Band without Robbie was a bar band writ large. I saw The Band several times in the ‘80s with the Cate Brothers {some of the latter Band’s fill-in members}, that only made you ache for greatness. Robbie was The Band’s Greatness, and The Band were co-conspirators.

I know it wasn’t easy for Eddie to write that to me. He loves Levon, and I do, too. In fact, shortly before Levon died, I’d been thinking about profiling him at what had become known as his Midnight Ramble, Levon and often distinguished guests jamming throughout the night in his Woodstock barn, in order to keep a roof over his head. Eddie had recently seen him play, drumsticks taped to his hands so he wouldn’t drop them, and told me I’d better get up there if I was going to do it. He didn’t think Levon had much longer. I had a pretty full slate at the time, and so put it on my to-do list. Then Levon was done in by throat cancer before I could make it happen.

On the day he died, I felt like I’d had the wind knocked out of me. I laid down on my bed with my wife, who had no particular attachment to him, and I said, “Levon Helm’s dead. Here, listen to this.” And I put a song on a repetitive loop. Levon and his band, or Robbie’s band, or whoever’s band you want to call it – but they were The Band, once upon a time. Him singing “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” at their last waltz – the last time they would all play together publicly, as a band.

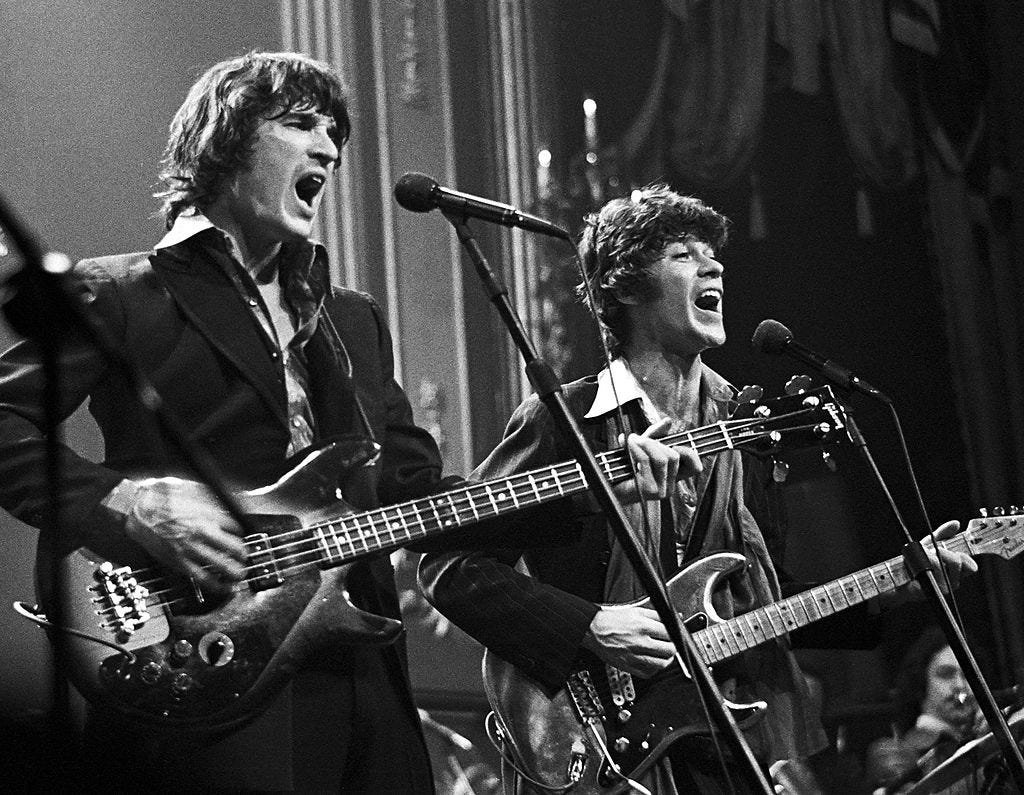

(Levon and Robbie, back when they could still get along.)

Robbie has said that his original intention was to pull them off the road, to save the people he loved and made music with, and after they’d played their last concert, they could all get healthy, regroup, and come back and make records. But everyone forgot to come back. Levon and his partisans would say that years later, they did come back – playing lots of shitholes like the one Richard Manuel died in when the Band was only running on half its cylinders, with not much money behind them, thanks to Robbie pulling the plug and moving on to his solo endeavors.

Whatever.

I realized, while weighing my old pal Eddie Dean’s words, that I no longer care who is to blame, and there is no need to apportion any. I love them all. There is no need for me to choose sides. Because in their best songs, they were all on the same side. And that is what we are ultimately left with. Whatever their beefs of the time were with each other, these were five men who made music I still hold onto, even if 4/5ths of them are no longer capable of making any. And on that day – Levon’s death day – I got lost in the song. The song Robbie wrote for him to sing, so that in Robertson’s telling, Levon could sing it better than anyone could sing any song. It was about as unlikely a subject for a liberal Canadian to write about (The Band supported Jimmy Carter). It was a song about a Confederate soldier named Virgil Kane, who served on the Danville train. Who was hungry, and barely alive. And whose brother was just 18, proud and brave, ‘til a Yankee laid him in his grave. And even those of us who rooted for the Yankees, as I did retroactively, and even Harriet Tubman herself, might feel the universal pain that isn’t Southern pain, but human pain. Of getting demeaned. And being defeated. And having you and yours’ faces rubbed in the dirt. And rising up anyway to sing of your travails, as so many Black blues and soul singers, who greatly influenced The Band, had done before them. All that pain, to The Band’s thinking, came from the same place, and spoke the same musical language.

Before Robertson wrote the song, Levon had driven him to the local library near Big Pink, so the former could research it, and internalize the particulars of a tune that Robbie would write, and that Levon would sing better than anyone could ever sing it (certainly better than the atrocious Joan Baez version of their song, that spent five weeks atop the easy listening charts). The Band’s version, being one we would all remember. One we would play, still.

Levon, in his own telling, didn’t want to do The Last Waltz concert. He felt his band, maybe the greatest band (as echoed by Bob Dylan, George Harrison, and the like), was getting shut down before its time was up. Even if they had problems. Even if some of them might have been killing themselves not-so-slowly. He didn’t care. As the title of his documentary suggested, he wasn’t in it for his health. While tons of celebrity performers from their past made the scene that night at the Winterland ballroom in San Francisco, the place they’d played their first show together as The Band in 1969, and where they were now playing their last (everyone from Van Morrison to Joni Mitchell to Dylan graced the stage that night), Levon was pissed that one of his personal heroes, Muddy Waters, might get wiped from the bill due to overbooking. While Neil Diamond was still on it. Neil Effing Diamond - whose latest album Robbie had produced, explaining the non-connection connection to The Band, but of whom Levon said, “Go tell Robertson to tell Neil Diamond we don’t even know who the fuck he is!” (Side note: Muddy ended up giving one of the best performances of the night, singing “Mannish Boy” with an elated Band backing him, Paul Butterfield using a circular-breath technique to sound like he’s holding the same note on harp throughout the entire song.)

But then all the acrimony fell away. Or at least it appeared to. And The Band did what The Band did best, one last time. Maybe better than anyone could do when they sang and played in near harmony, and were locking into each other. I’ve often thought about what fueled Levon’s passion that night, as the son of an Arkansas cotton farmer sang words and music written by his Canadian little brother, about an American war that had ended over 100 years prior, while the war within him might have just started raging against the man who’d penned his tune. Maybe it was fueled by what would become Levon’s seething resentment of Robertson. Maybe it was his love for the same, whom he considered himself betrayed by. Brother vs. Brother. The Civil War’s very prom theme. Maybe it was some combination of both, as love and hate often bump in the night, and aren’t always the easiest of emotions to keep straight. Sometimes, we hate extra hard because our love has gone sour. The people we’re most hurt by, being the ones we’ve fully admitted into our lives.

But whatever the case, whatever was animating Levon, The Band left their all out there on the stage that night, in that wonderful song. All five of them playing and singing with everything they had, and maybe with what had already left them. And thank God they did, because it would have to do us until the end of time – the five of them never performing together onstage again. But that night, brought to us by Robbie – it couldn’t have happened without him - Levon played and sang like his family was on fire, and they needed blowing out. And all his Band-mates did the same. They were, in fact, burning to the ground together, even as they sang their lost-cause anthem. So if you want to know what imperfect perfection looks like, just sit back and marvel at this:

In the 2019 documentary, Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band - the subtitle of which could make Levon retch in his grave - Robbie offers that when Levon was on the cusp of death in 2012, he tried to end their long Cold War by visiting Levon in the hospital. He went to his bedside, and held Levon’s hand, and told him he’d see Levon, his musical brother in arms, on the other side.

Now that Robbie himself has gone over to that side eleven years later, here’s hoping his promise wasn’t just for show. That he and Levon have met up again. And that along with Manuel and Danko, they are striking up The Band one more time. If so, the lineup’s incomplete. Garth Hudson is still here, for now. So maybe God can spot them an organ player – Dr. John or Billy Preston could hold things down in the interim. But it’d be worth doing. Even the Angel Gabriel would put down his horn to hear that holy ruckus.

Bonus Track: I realize I’ve already loaded you up with so much music, that there’s really no call for a Bonus Track this time out. Unless I want to link to some of the best Robbie Robertson solo songs that I gave short shrift in the above piece, all of them from his first two solo albums: 1987’s Robbie Robertson and 1991’s Storyville, which were far and away his finest. The first of which was produced by Daniel Lanois and contains guest shots from the likes of U2. The latter of which was a New Orleans-flavored album featuring everyone from Neville family members to the Rebirth Brass Band. The two albums contain keepers like Night Parade , Testimony , Hold Back The Dawn, Soap Box Preacher, Shake This Town, and Sign of the Rainbow (some pretty glorious guitar work and Aaron Neville back-up vocals on that last).

But the song I will leave you with in a full-on display link, which I’d never heard before researching this piece, is The Band playing a tune called “Little Birds,” which Levon’s dad taught them. They played this at one of their very first concerts at San Francisco’s Winterland ballroom in 1969, where they’d end up playing their final concert years later. It’s from an audience recording. So the quality is poor, but that almost makes it sound better. Like it was being played on some ghostly carousel from yesteryear. Which it kind of was, even when they were playing it the first time around.

Fuck! Matt Labash just wrote the best piece on the Band that I ever, I mean ever read. From my first play of Big Pink in ‘69 to seeing their last NY concert at the old Academy of Music on 14th street the Band was my special musical connection. Sure I loved the Stones, and the Allmans were our party band with no equal, but when I wanted to dig deep, or as deep as a 19 year old could hope to, I turned to the men of the Band. My college buddies didn’t get them, thought they weee strange and not rocky enough. Me, a Latino kid from the Bronx hiding out in the Catskills for college, they were transcendent. I will never forget them and when I feel a desire to relive my innocent youth, on goes Cripple Creek.

Thanks Matt for an amazing tribute not just to Robbie, but to an ensemble that defined my generation of music lovers.

Love and grief from a fellow artist.

Who else but Matt

could pour his soul

into giving The Band to us

with such passionate eloquence