Fall Guy

Getting through autumn with Thoreau

When I was a teenager, I didn’t have much use for autumn. Because autumn meant the end of summer, and the end of summer meant the end of all that was good and righteous in my world. No more staying up half the night, and waking up at the crack of noon. No more watching “my stories” (Days of our Lives, All My Children), as the eighties housewife in me used to call them. No more feeling like an outlaw who just knocked over a stagecoach, mowing geriatrics’ postage-stamp lawns for thirty-dollars-an-hour - cash under the table. It was money the IRS would never lay its sticky mitts on, unlike with the paychecks of my naïve compadres, who were dumb enough to labor at the mall food court, even if they met more girls while working the Chick-fil-A sampler tray.

As autumn fell hard, and we were suddenly locked into the 8-to-3:30 grind, plus commuting and homework time, we’d no longer have room for marathon pick-up games at the neighborhood basketball court, as we had all summer. There, in a pre-wokerati-era, we used to split into segregated “salt’n’pepper” teams, as they were called at the time (white kids vs. black kids). Though in fairness to us salts, that was the black kids’ fault. They didn’t want to be saddled with guys like me – slow people with nine-inch vertical leaps – not much help under the boards. Once, the MLK in me had a dream, and suggested racial integration. How about we just choose up sides, and play shirts’n’skins instead? But I was brusquely dismissed by the other team’s point-guard, Gary, a husky gentleman with a growly demeanor who used to taunt you with “he-ain’t-got-no-heart” as you were trying to force him to his weak-side. We didn’t push. We all knew Gary didn’t actually hate white people. He just didn’t want to take off his shirt for fear of playground insult-comics making fun of his gelatinous moobs.

We salts would’ve gotten smoked, too, if it weren’t for our star player, Lawrence, a thundering semi-truck of a man-child who had the jackrabbit, ambidextrous skills of a nimble playmaker, but who had the body of Charles Oakley, splatting opposing players like bugs on a windshield whenever he felt like driving the lane, which was pretty much every time he touched the ball. You took the charge at your own risk. Lawrence later went to prison for pouring gasoline on two people, then setting them on fire (killing them both), due to a dispute over changing the television channel. The papers say he then later strangled a guy to death in the prison shower, who was serving life sentences for killing his own two young children. Perhaps Lawrence was just trying to square his karma, on that last count. Though flashing back, this all made me relieved for the other team, that they never called Lawrence for traveling, which he did without conscience.

Ahhhh, childhood innocence……….

Even if school busied me when summer turned to fall, interrupting my All My Children regimen, as you get older, you realize you no longer need the faux tension of soap operas with their preposterous story arcs, their out-of-nowhere plot twists, their treachery, and duplicity, and evil twins. Adulthood provides enough of that on its own, minus the evil twins.

And so, I became a lot more amenable to autumn, now that summer was no longer special, and the grind ground on all year. The light was softer and the air crisper, the trees set ablaze in reds and yellows. It appealed to the melancholic in me. The world became a James Taylor song.

It’s not that I adopted so many fall rituals. But I did have a few. You have to, if you have kids: Visiting the local pumpkin patch. Raiding the farmer’s market for dried corn-stalks and otherwise useless gourds to put on your porch, making the Joneses envy your harvest. And then, of course, there was Halloween.

For about a decade straight, we made a huge deal out of it, even if my oldest (now 22), was not that into it. He was non-Halloween compliant. One year, we tried to dress him up as Spider-Man. But he refused to wear the mask, claiming, “It’ll cover up my dimples.” (He’d apparently been spending too much time with his doting grandmother, who’d convinced him he was a matinee idol.) Another time, we tried to dress him as a western sheriff, but he refused to wear a cowboy hat, or to put a plastic gun in his holster. Why, we don’t know. (Maybe like all great Old West lawmen, he realized the trick to establishing order was unmussed hair and a willingness to clean up the town with your bare hands.) Our most successful outing was dressing him as a waiter, due to the low maintenance. The entire costume consisted of wearing black pants, a white shirt, and draping a towel over his arm. We’re still not sure whether anyone knew what he was supposed to be. But if you had a messy spill during trick-or-treating, he at least looked capable of swabbing it up.

During these golden autumns, we had an unbreakable ritual. All the parents would get together on a pick-up truck trailer filled with hay bales, motoring around my in-laws’ neighborhood while drinking beer. The kids would go door-to-door, beseeching sweet treats. Then when they climbed back into the trailer, we’d praise them. “You did great!,” we’d say, as we picked them clean of their Almond Joys or Kit Kats, adding, “You go ahead and keep those Tootsie Rolls,” loathsome unchewable little things which, if they broke their baby teeth on them, they’d grow more.

Our driver, Gil, would wheel us all the way over to my wife’s Aunt Mary’s, about three miles away. Even in face-numbing cold, it was always worth the trip. Mary was a bit of an eccentric. Her specialty was forming one-dollar bills into replications of folded shirts, a sort of calling card. When she’d go to a restaurant, she’d bring these money-shirts, and count them out for the help, just to impress them. Once, at a local Amish market, in which the hostess was what we now call “a little person,” she doled out her money-shirts as such: “One for the waitress, one for the manager, one for the midget.” Nobody, not even the midget, was allowed to spend the money-shirt, the same way you wouldn’t spend a Rothko or de Kooning. It was Mary’s priceless art.

When we got to Mary’s house, she always dispensed the best candy of anyone in a many-mile radius. No chickenshit caramels or jawbreakers. Just full-size Mr. Goodbars and the like. Premium chocolate. It really made stealing our kids’ candy worth the commute.

The entire autumn ritual had a pleasing sameness about it. In fact, every year, I used to say to Gil’s wife, Debbie, just as a time-marking mind-screw, “Hey Debbie, we did this exactly one year ago. And when we do it again next year, I’ll remind you that we’ve had this conversation. And another year will have passed, and we won’t believe it went that fast, and that we’re having this conversation yet again.” We had that conversation every year for years. Until we didn’t.

I got busy or was on the road during Halloween hayride outings and missed a couple in a row. Aunt Mary left us, going to that big confectionery in the sky. Gil and Debbie got divorced – I haven’t seen our once faithful hayride driver in years. Our kids got older, which was the biggest culprit. They aged out of childhood make-believe. And Halloween just became a day like any other. Something you had to buy candy for, in case other strangers’ kids came to your house, which they increasingly don’t – this being the Age of Distrust and all. We fall into the rhythm of our rituals and think they’ll last forever, even if nothing does. Like most good things, they often end before we know they’re over.

And yet, there is still a ritual I hold onto when the leaves turn. Every year, I try to read the underscored highlights in my copy of Henry David Thoreau’s Autumnal Tints. The essay-length slim volume is not considered one of Thoreau’s major works – my local libraries don’t even carry it. But to me, it is.

It’s his celebration of fall, where other writing about the season often feels like a dirge, as the death it portends isn’t even metaphorical. Despite all that blinding beauty and riot of colors, as leaves lose their chlorophyll and their carotenoid and anthocyanin pigments paint the town red and yellow, a sadness hangs over the season, since by the time the leaves put on their light show, it means they’re ready to drop to their deaths. The beauty we wish so badly to hold onto never lasts as long as the barren, cold winter. Which is coming.

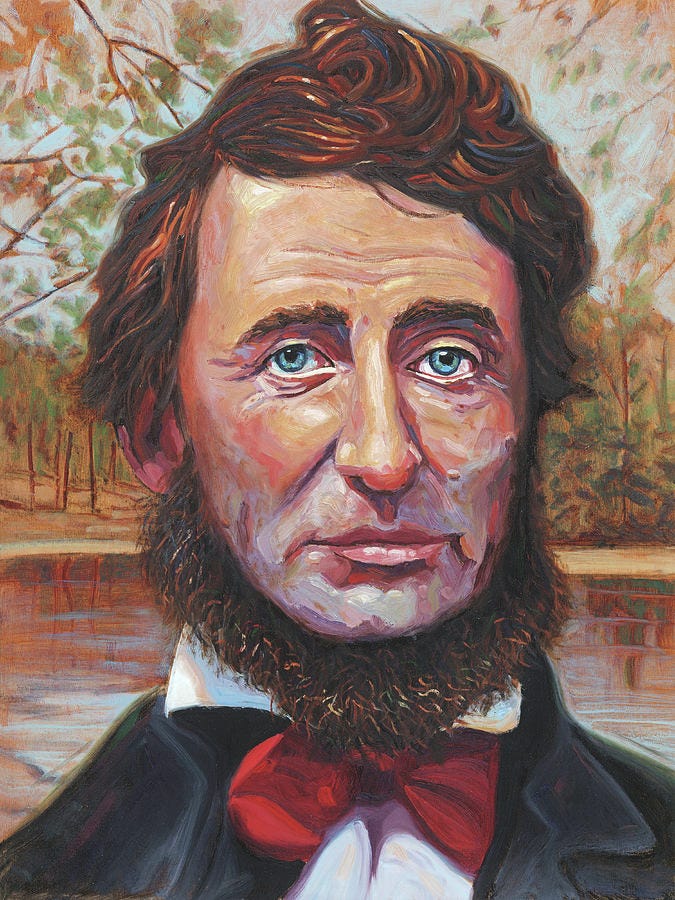

Thoreau, the man who made his biggest mark in this world by becoming a Transcendentalist squatter on Ralph Waldo Emerson’s woodlands around Walden Pond, then writing about it, knew what death meant, and in fact wrote Autumnal Tints right up until his own, as tuberculosis was taking him down, finally ending his earthly hitch at the age of 44. He died with his metaphorical boots on, according to Emerson, who wrote: “Never saw a man dying with so much pleasure and peace.” When Thoreau’s Aunt Louisa asked him if he’d made his peace with God, he responded, “I did not know we had ever quarreled.”

The Atlantic Monthly published his essay after his death in 1862. And when I hold my heavily underlined copy, I’m struck by how much life a dead-man-walking can pack into so few pages. Thoreau wrote like the Pentecostal holiness preacher, Brother Claude Ely, sang: there ain’t no grave gonna hold his body down. In fact, Thoreau regarded trees as near spiritual totems, and a village needed “these innocent stimulants of bright and cheering prospects to keep off the melancholy and superstition.” The maples, he wrote, “are cheap preachers, permanently settled, which preach their half-century, and century, ay, and century-and-a-half sermons……ministering to many generations of men; and the least we can do is to supply them with suitable colleagues as they grown infirm.”

The naturalist in Thoreau could identify every tree, shrub, and weed. From purple grass to scarlet oaks, he knew, from endless observation, nearly down to the day when everything would put on its autumn raiment. The particulars, “the scientific account of the matter” were no secret to him. Even if “I am more interested in the rosy cheek than I am to know what particular diet the maiden fed on.”

As the painted leaves of his day were about to fall, he recognized that another year, too, was about to do the same: “October its sunset sky; November the later twilight.” (Even if our mid-Atlantic sunset skies now occur more around November. Thanks climate change!) And yet, when the leaves fell, Thoreau didn’t mind that either, as they made “the whole earth….a cemetery pleasant to walk in. I love to wander and muse over them in their graves. Here are no lying nor vain epitaphs.” He added:

How beautifully they go to their graves! How gently lay themselves down and turn to mould! – painted of a thousand hues, and fit to make the beds of us living. So they troop to their last resting-place, light and frisky. They put on no weeds, but merrily they go scampering over the earth, selecting the spot, choosing a lot, ordering no iron fence, whispering all through the woods about it, - some choosing the spot where the bodies of men are mouldering beneath, and meeting them half-way. How many flutterings before they rest quietly in their graves! They that soared so loftily, how contentedly they return to dust again, and are laid low, resigned to dust and decay at the foot of the tree, and afford nourishment to new generations of their kind, as well as to flutter on high! They teach us how to die. One wonders if the time will ever come when men, with their boasted faith in immortality, will lie down as gracefully and as ripe, – with such an Indian-summer serenity will shed their bodies, as they do their hair and nails.

I read Thoreau in autumn, because he helps me see what’s right in front of my face, but what I’ve been missing all along. In fact, he warned of it, since “nature does not cast pearls before swine. There is just as much beauty visible to us in the landscape as we are prepared to appreciate – not a grain more…. Beauty and true wealth are always thus cheap and despised. Heaven might be defined as the place which men avoid.”

I’m avoiding actual Heaven myself, at the moment. Though I’m grateful to Thoreau for finding plenty of it on this earth. And I hope to see him there someday. I suspect he’ll be gorging on Aunt Mary’s Mr. Goodbars, if she’s not too busy passing out money-shirts to midgets.

Seasonal bonus track: the late, great Eva Cassidy singing Johnny Mercer’s “Autumn Leaves” at Blues Alley:

God gave you a gift, Matt; thanks for sharing it with us. I laughed out loud about Aunt Mary and her money shirts, felt sad about Gil and Debbie's divorce, and got choked up when reading Thoreau's tribute to how gallantly leaves die. Reading this helps me realize there are more important things in life than Steve Bannon getting indicted for being such a dickwad (I know that's not really why he got indicted, but man, he sure is one.)

Thoreau would love it that we gather here to read this gorgeous elegy to his leaves and to him.

How gladly he shares his immortal soul with us! We see the autumn beauty through his eyes.

"The words of a dead man are modified in the guts of the living" (as Auden wrote of Yeats.)

I love that Matt's guts and tender words bring us his own fresh vision of Thoreau, so that we can have Henry David with us as we scuff gladly through the autumn leaves of our lives.