Holy Books

Jim Harrison's words might not be the inspired Word of God, but they'll do in a pinch

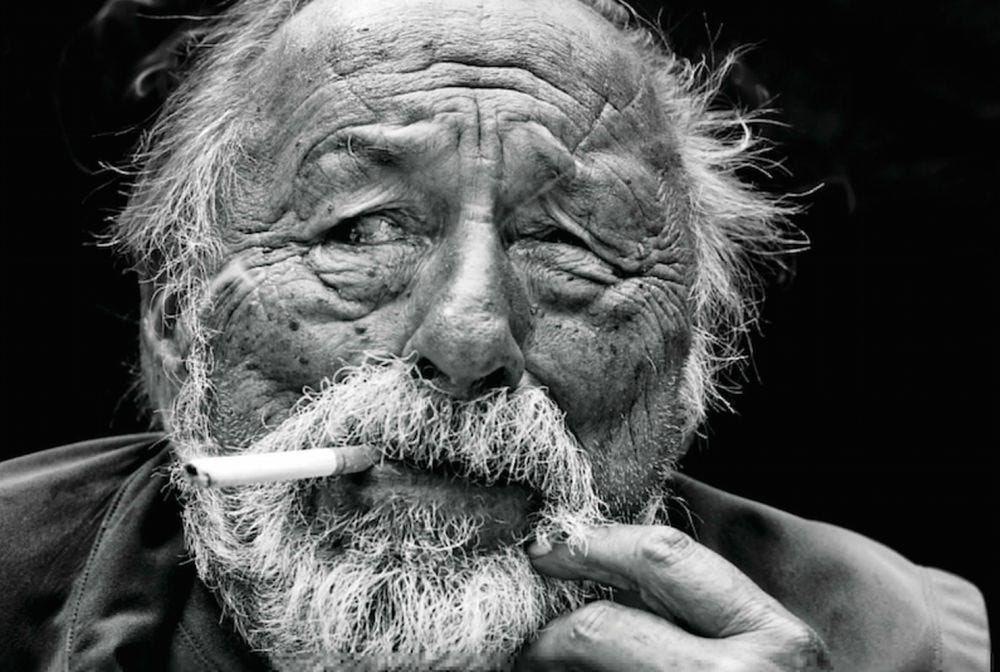

Whenever I’m guest lecturing in schools, churches, or prisons, I’m often asked a version of a question that goes something like: “You quote Jim Harrison an awful lot. What gives? Are you amorous for a one-eyed comboozelated poet/novelist/essayist who has been dead for nearly a decade? Is his estate giving you a cut? Or do we just need to pitch in and buy you a Bartlett’s so you can mix things up a bit?” Kids are cruel, to say nothing of church ladies and inmates.

I look at these people who don’t technically exist (they’re composite characters) with pity. For me that is like asking, “Why would you keep returning to the Psalms and Proverbs?” Well, only because they contain wisdom and beauty, horror and despair, hope and lyricism, wildness and rhapsody and hard truth. Failing to regularly revisit Psalms and Proverbs – much like not revisiting Harrison – would be like admitting you don’t have much stomach for sunsets or full moons or your dog sitting by your side in front of a roaring fire while you nurse a glass of something strong to take the edge off a world you will never fully understand.

We tend to love the people who love (and hate) the same things we do. And in that department, Harrison ticked most of my boxes: he loved dogs and birds, walking through woods and fly fishing the rivers that run through them. He had large appetites. He loved food, perhaps too much. (He once wrote a piece for The New Yorker in which he consumed a 37-course, 11-hour meal in a restaurant in Burgundy, which, as a professional poet, he did not pick up the tab for.) He thought the cure for every ill was more red wine and fresh garlic. (Not in the same glass.) He loved words, and writers who weren’t afraid to use them in full-bodied fashion. While he appreciated Hemingway’s craft, he once regarded him as “a wood stove that doesn’t give off much heat.” Give him writers whose offerings had stronger circulatory systems: Rimbaud and Lorca and Henry Miller, the last of whom Harrison said “saved my neck” when he was young, by offering “more abundance – mental heat, experience, jubilance.”

Harrison hated bloodless writing by eunuchs who came out of MFA mills, who’d had their natural neuroticism exacerbated while getting worked over in workshop. In an eighties interview, Harrison pointed instead to the likes of Gabriel García Márquez: “Look at Chronicle of a Death Foretold – it’s such a strong juicy death in primary colors. It’s not a pastel death with a film of snot over it – chichi snot at that. It’s right there. That’s an aspect of Lorca’s poetry I’ve always admired. I was in a snit the other day over the infantile mechanics of minimalism, the extreme posture of fatigue. Minimalism is that old cow, Naturalism, rendered into the smallest of print.”

He read widely and deeply, but hated Theory. He liked paragraphs that sing (believing music is often an essential ingredient while writing) over snore-inducing didacticism. “I can’t stand art that’s preachy,” he once said. “If somebody tells me {he} has things he wants to say, I say, ‘Well, I don’t care, everybody has things they want to say.’ It’s like Philip Roth puts it, anybody on the subway usually has a better story than an artist does. Because they’re intensely occupied with life.”

His advice to young writers? Probably the best of its kind: “Just start at page one and write like a son of a bitch.”

We lost Jim Harrison in 2016. As I wrote of him shortly after his death: “A one-eyed mystic and mad man (he lost the use of an eye – a “milky sparrow in its socket” – after a childhood argument with a girl who smashed a bottle in his face), Harrison saw a lot more than the rest of us, having what all great point guards possess: complete court vision.” He expired of a heart attack in his writing chair, or on the floor beside it, in his casita on the Arizona/Mexico border, where he split each year, first between his home state of Michigan, and later, with his adopted state of Montana. I suppose it was a “good death,” as was said of his protagonist who died duking it out with a grizzly bear in his most famous work of fiction, the 1979 novella Legends of the Fall (which became the 1994 Brad Pitt vehicle). After all, Harrison died in his writing stirrups, running out of time before he ran out of things to say. Also, he successfully dodged a deadline, which writers of every stripe have to respect. It’s a good way to go if you have to. And spoiler alert: we all have to.

I never met the guy, deliberately passing up the one chance I had to do so when a mutual friend offered to introduce us. It’s a decision I don’t regret – not much, anyway - as I hold Harrison in such high esteem that I couldn’t risk being disappointed. But lucky for me and the rest of us, we don’t have to miss his voice. He said and wrote a lot. Despite his protracted absences from his writing desk – fishing jags that lasted months (such as his seventies sojourns to fish for tarpon with the likes of Tom McGuane and Jimmy Buffett in the Florida Keys), weeks-long drives through flyover America to blow out his mental blockages, his sybaritic obsession with food (both preparing it and consuming it) and wine (just consuming it) - he was good for no fewer than 12 novels, nine collections of novellas, 20 volumes of poetry, five essay collections, one memoir, six screenplays, and even a children’s book, The Boy Who Ran to the Woods.

With that kind of output, it’s small wonder Harrison needed to run to the woods with some frequency himself, to his cabin in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, as a sanity saver. Even though he once admitted: “For years I assumed that the cabin restored me from and for my battles with the ‘real world’ where, in fact, it only prepared me for more time at the cabin.”

It would take a long time, then, to become a Harrison completist. I’m still working through that massive oeuvre myself, figuring it’ll take the rest of my life to do so. Which I like the idea of, the same way I treasure the imposing stacks of red oak rounds in my backyard. Some of them will rot before I ever get around to burning them. But it’s nice to have continuity, while knowing that there’s good wood in front of you that needs splitting - something to do that’s worth doing.

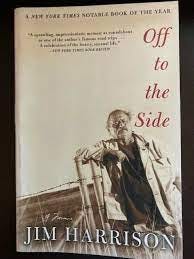

Despite his plowing headlong into all the aforementioned literary genres, Harrison thought of himself as a poet first and foremost. As he put it, “Like {Ezra} Pound says, ‘Poetry is news that stays news.’” I love Harrison’s poetry. Though for my money, the two books I return to as regularly as I do the Psalms and Proverbs are a collection of interviews with Harrison over a nearly 30-year period, edited by Robert DeMott, called Conversations With Jim Harrison, and Harrison’s own memoir, Off To The Side, both released the same year (2002).

Nearly all the quotes you’ve already read are from one of those two books. And in the interest of eliminating clunkiness going forward, I will not specify which of the two the quotes come from, except to say that “Harrison said” if it’s the interview book, and “Harrison wrote,” if from the memoir.

If you treasure freedom, as I think most of us at least pretend to, Harrison was an unmitigated free bird, his mind rambling all over the place, seeing no clean delineation between man’s nature, and nature itself, and birds and dogs and poetry and alcohol and fishing and food and politics and God and whatever else might come our way. Which, if you’ve read my Slack Tide mission statement, even if I detest mission statements, you’ll know means that he was my kind of writer, and presumably yours, if you’re the type of person who subscribes here. He was the kind of writer I like to call a big-ball-of-life guy. He wasn’t necessarily a specialist. The entirety of life was his subject.

Because of this, when I’m feeling low, and need direction, or even when I’m feeling high, and need words of celebration, I often turn to these two heavily-underlined volumes to hear Harrison lay out things that my subconscious has just barely intuited, but which it knows in its bones are true. “Truth.” What a sweet-ass word! Yet so few people in our modern public square tell it. Which is probably why I treasure Harrison’s truth so much. The scarcer something is, the greater its value.

And so – and I hope you’ll forgive me for quote-dumping here, though they’re good quotes, so I suspect you will appreciate them if you go along for the ride – I turn to Harrison on any number of subjects.

Harrison loved to drink, but also recognized how drink can bite you if you do too much of it. When friends of mine tell me they need to stop drinking – and many have – I always tell them, “We’re always the last to know when we need to quit something that harms us. So if you think you need to quit something, you do.” And yet, Harrison, the committed drinker, gives the best reason I’ve heard for not drinking too much. As in most of his life, he cherished balance – balance being the answer to most of the problems that bedevil us - even if he didn’t always practice it. But he wrote:

In drinking, as in everything else, the path is the way. What you get in life is what you organize for yourself every day. There is an ocean of available wisdom from Lao-tzu to Jung to Rilke. It’s there in preposterous quantity. If you drink way too much it will kill you and the souls of those around you. If you moderate you have a nice life…..We don’t have much freedom in this life and it is self-cruelty to lose a piece of what we have because we are unable to control our craving.

Beat that, AA.

And here, Harrison speaks about withstanding implacable blows, such as his beloved father and sister dying in a car accident when he was a young man, which left a mark:

I thought, isn’t this strange, any possibility of agreeing with the world has just left me……I know you have to keep one ear for your friends and one ear to the conversations in the world around you. I see it, hear it out there, this malaise. It’s because there’s no spiritual life, of course, and that makes for an enormous vacuum because we’re spiritual creatures……Back to Lorca, what is poetry but love, suffering, and death? Or, the idea of making a heap of all that you have met. I haven’t been nearly as unflinching as I’d hoped to be, no. But that’s part of my makeup. Early on, my inability to face certain horrors as directly as I should have contributed to that. But, then I’m always looking for the song I could make out of it, too. I can’t quarrel with the limitations which are part of me – everybody has the severest of limitations. You are ultimately what you collectively wish to be. When someone says they could be so much more, I say well, you better get started right now, who’s stopping you? Face it, there’s an anchor tied to your ass.

And yet, even in recognizing our limitations, he detests self-pity, swimming against the self-help/victomology current, writing:

Our cures are interesting. Our infirmities aren’t. Everyone knows about infirmities. Our occasional luminescences are what contribute to the human condition. The idea that somebody can say, for instance, that I get up and work hard – well, try saying that to the Chicanos. Give me a break! I grew up in a rather poor family of dirt farmers in northern Michigan. Can you imagine the idea of a professor teaching six hours a week and whining about it?

As with any honest man, he doesn’t pretend to have all the answers. When asked whether his cures for what ails us come through his writing, Harrison said:

Through your art. That’s the only form I have. I mean, it’s quite enough, frankly, if you think about it….I said once, I can’t give anybody advice except to say, ‘more red wine and garlic.’ Or, as I admitted in the After Ikkyu book of poems, I’ve now closely advised seven suicides, so I’m backing out of this. I mean it came to me to say, ‘What should I do?’ Whatever I had to say wasn’t enough, so…….”

I realize that for people looking for hard answers, that wasn’t one. But sometimes, humility is its own strangely refreshing answer. Knowing what we don’t know, which is plenty.

And so, as much as Harrison, as such a prolific writer, spent life living in his own head, he couldn’t stress enough the importance of escaping the prison of your own. As he wrote:

In northern Michigan it is frequently cold in the summer, or too hot with clouds of mosquitos, blackflies, deerflies, wasps, and hornets. But it was wild, crisscrossed by old logging roads, and properly used to adolescent exhaustion the natural world can draw away your poisons to the point that your curiosity takes over and ‘you,’ the accumulation of wounds and concomitant despair, no longer exist. The immediate world for hours at a time becomes quite beyond self-consciousness. You are more purely the mammal beneath the clothing of the culture, the civilization. The reading will take place in the evening near the oil lamp on the roseate oilcloth covering the picnic table in the corner of the cabin. But now for the time being you are merely wandering with your five senses, which, without your usual self-absorptions, are uncannily alive…..I reenter the woods and rivers with a moment-by-moment sense of the glories of creation, of the natural world as a living fabric of existence, so that I’m both young again, but also seventy thousand years old.

I recognize that none of what I just wrote/shared is “on the news” as we say in our dysfunctional trade of the immediate and diposable. Yet it kind of is. Because how to escape the bad news that besieges us, each and every day, is news in itself. News of how not to lose what we know is true in a sea of falseness, and lies, and algorithms eager to feed our cynicism and paranoia of how it’s all gone wrong, which in fairness to the algorithms, it largely has.

But though I might be beating against the tide here, I stubbornly maintain that there is a better way. To ignore it all, or to at least put these things in their proper place when they refuse to be ignored: discounted, in the mental-junk bin. Instead, embrace what is beautiful and true. Like this Harrison paragraph, of which there are many more. (I only scratched the surface). As he wrote of late-life bird-hunting with his dogs:

As my dogs have aged and slowed down I’ve been amazed at how much they’ve conserved energy by moving directly from covert to covert without the aimless bursts of speed that typified their younger behavior. Hopefully your concentration on what you are doing is close to that of the dog and after a couple hours, when you both are quite tired, you find that you have been so immersed in this creaturely behavior that you haven’t had a worrisome or contemporary thought since you got out of the car. You have plenty of time for those when you reach home though the act of cooking dinner can further delay their arrival. If you hunt or fish a couple of weeks in a row without reading newspapers or watching television news, a certain not altogether deserved grace can reenter your life. Newsworthy events and people, as always, have gotten along in the usual ways without your mental company.

Bonus Poem: One of my Harrison favorites, “Debtors.”

They used to say we’re living on borrowed

time but even when young I wondered

who loaned it to us? In 1948 one grandpa

died stretched tight in a misty oxygen tent,

his four sons gathered, his papery hand

grasping mine. Only a week before, we were fishing.

Now the four sons have all run out of borrowed time

while I’m alive wondering whom I owe

for this indisputable gift of existence.

Of course time is running out. It always

has been a creek heading east, the freight

of water with its surprising heaviness

following the slant of the land, its destiny.

What is lovelier than a creek or riverine thicket?

Say it is an unknown benefactor who gave us

birds and Mozart, the mystery of trees and water

and all living things borrowing time.

Would I still love the creek if I lasted forever?

Bonus Track: Harrison used to fish for months at a time in Key West, back before it was a god-awful tourist depot. In keeping with that spirit, here’s perhaps my very favorite John Mellencamp song, the 1996 tune, “Key West Intermezzo.” And yes, that is Matthew McConaughey in the video.

Jim was a friend. Somewhere there's a photo, taken by a Frenchman, of Jim and I holding hands in a Montana field. He once told me, "Sherman, you're one of them rez Indians who's got too much Catholic in him. Lighten up." I'v got stories about him that I can tell and others that I can't! Thank you for writing this ode to him. I fear he has been forgotten by too many people in the book world.

Matt, Thank You for the introduction to a writer I will be soon checking out.

These days, this sentence should be in every brain, every morning, "Newsworthy events and people, as always, have gotten along in the usual ways without your mental company."