Love Among The Ruins

A word from Father Rick Frechette on how to manage your righteous anger

As longtime loiterers around here know, I believe in transparency. At least when I’m not trying to hide something from you. (Where else can you get the kind of honesty that admits its dishonesty? Which is why you should become a paid subscriber now if you care about Truth, even an imperfect version of it.) But here are a few realness cards slapped on the table: What’s bad for the nation is often good for me, personally. I eat conflict for breakfast, along with a mixed-berries smoothie. (The first causes inflammation, the second reduces it.) Don’t let the Zen-like bluebirds and fly fishing pieces fool you — I am utterly comfortable writing about discomfort. Writing about Trouble makes subscriptions surge, and makes the uneasy feel like they have company (and almost everybody is uneasy these days). Also, chicks dig it. Except for my wife — the only chick who matters — who’d prefer I stick to bluebirds and fly fishing. But sometimes, we have to sacrifice for our art. In other words, I am putting my marriage on the line for you, ever the selfless servant, just like Elon.

That said, all the bad news — the unprecedented month-long assault on our republic by one narcissistic billionaire I didn’t vote for and his ketamine-addled pretend-populist sidekick who nobody voted for — has left me sour and bitter and ugly. Why can’t half the country — plenty of whom I count among my family and friends — acknowledge reality? I’m nobody’s liberal, but I can clearly see that this beautiful thing of ours is getting dismantled, piece by piece. We are in real jeopardy at the moment. Is it that hard for them to pick up a newspaper, or to watch five minutes of something that’s not State TV (Fox), which even one of their own house propagandists just admitted that they essentially are?

I would hope not. And yet, I keep feeling myself hoping in vain. Which is to say, veering toward hopelessness. And when I become hopeless, I do what I’ve often done when I feel up against the wall, and don’t know how to respond. I turn to Father Rick Frechette, a Catholic priest in Haiti, who I profiled 15 years ago, and who I have deliberately stayed in touch with since. Because Father Rick meets more trouble in a week than I do in a year or five. I first parachuted into his life when his mother had died, and the day after he buried her, we headed into the jaws of ruin at his home base in Port-au-Prince, after one of the worst earthquakes the world has ever known (the 2010 earthquake killed one out of every 50 Haitians). But even after I left, and wrote my story, the earthquake never really stopped. The ground always figuratively shakes there, even when tectonic plates aren’t grinding it out. For Father Rick (who became a doctor, in addition to being a missionary, just to help physically heal that unhealable land) endures quake-like instability nearly every day of his life. He faces down gangsters who kidnap foreigners, and cholera, and unspeakable violence and poverty and political chaos.

I don’t know how else to describe him but to call this priest the best Christian badass I know, something I don’t cop to easily as a Protestant. But he gets tough things done. He doesn’t cower at evil, but faces it down. The book of James tells us to “be doers of the Word, and not hearers only.” And however you feel about religion — even if you’re a stone-cold atheist — to know Father Rick’s work is to know that he is a doer’s doer. You hate religious hypocrites? Wonderful. So do I, even if I sometimes do a passing impression of one. But he is the opposite of one of those. Under the most trying circumstances, he doesn’t just rage against the dying of the light, rather, he illuminates the darkness with a blowtorch. All while maintaining his own generosity and gentleness of spirit — a hard trick to pull off.

So that is why, the other night, I wrote this to him:

Father Rick,

It's been a while since our last confession. (Even if I'm a Prot, and don't believe in confession.) But I know you enjoy puzzles, and I have one for you. The evil you have seen in your own country is now making itself manifest in ours, in no-joke fashion. Maybe nowhere near as severe as Haiti's (most dysfunction in the world is never as severe as Haiti's, as you well know.) But severe by our standards. I'm not afraid of calling it out. In fact, I do so all the time. Lack of nerve is not my problem. But, in doing so, I often feel betrayed: by my countrymen, some friends and readers, even some family members who can't see what is plain as the nose on their face. I know you've been bucking up against this for a long time, and do so constantly in your line of work. How do you deal with that? And not become bitter? Because when I've spent time with you, I do sense urgency, but never bitterness. What's your trick? Maybe even something I can share with my own readers, who struggle with the same.

Best,

ML

When I awoke the next morning, the below response had arrived. And I should caution you that as long as I’ve been writing Father Rick — which is 15 years now — he always, for reasons that have never been explained, writes back with poetic line breaks (even though it’s all prose), as well as infrequent caps and punctuation. Which somehow feels right to me as prose-poetry, so I don’t question it. Here was his response, as composed. (Just for clarity’s sake: the “Raphael” referred to below was his Haitian right-hand man, Raphael Louigene, who was like a brother to Frechette, and who stroked out of this world in 2023 at the age of 42 from the pressure he was under, Frechette says.)

Hello Matt

I totally get itJesus could not work a miracle in his home town

He was banalized there

Writers crampHe was blatantly called crazy by his family

People tried to throw him over a cliff

He was called Satan personified

None of that is any fun

I worry for the Biden parolees I have sent to USA

Like Raphael’s children

Under Trump

Who has managed to divide our family groupMy three brothers focus on their guns and their fear whites will soon be minority

I focus on a family that entered USA legally, works, pays taxes and waits for asylum even if Trump deleted their legality, it was a legal entryOur concerns (mine and my three brothers) seem to delete each others as I add non whites to the equation

At the end of the day

When you and I are seen as aberrant and dangerous

When we look in the mirror

we have to ask ourselves

How true is the one we are looking at in the mirror

what we think of our trueness to ourselves has to Trump (so to speak)

Everything elseWe cannot betray ourselves

Our insights

Our obligations to set things rightOnce I had a beautiful chance to kill an enemy by not helping him with his deadly cholera.

he was in a third world prison and I was the only person on earth who could find the way to help himIt was delicious

the thought of seeing him die in his own foul excrementI thought to myself

Only God and I will know that I didn’t helpThen I realized

The two most important opinions about me

In the whole cosmos

That I should be concerned about

are mine and God’s!And I restored his health

I think you can try a new skill

How do I both defend my brothers’ concerns and defend mine

Instead of "either or" get skilled at "both and”

For example

I believe in immigration control

And suggest we start with criminals and not Biden parolees who entered legallyI believe in making America great again

I believe making our allies great is a big part of thatI agree in cutting government waste and fraud

But I believe it is wiser to analyze and act in streamlined ways and not slash and burnI respect the elected officials

Musk is not one

etcThese are first thoughts but also remember this as you see the glass half empty

more than half the USA is in your corner, and at least ONE priest in HaitiKeep the faith

Forgive the draft format

In that response, you can see a flicker of the light I saw while profiling him. So…..while I’ve buzzed by some of the contents of that profile in these pages a few years back, I once promised to run the entire thing, all 10,000 words of it. Now feels like as good a time as any. Yeah, I know that’s long. But who cares? The republic will still be burning when you get done with it, so you’re not missing much else. In 23 years of being a magazine reporter, paid to find interesting people for a living, this was probably the most intense reporting experience I ever had. In this story, we encounter life and death and fire and dark laughter in the face of misery and heaps of broken bodies and dogs eating cadavers and five children buried to a single cardboard coffin in the un-air-conditioned Port-au-Prince morgue, where we had to smoke cigarettes and pour rum on our lips just to kill the smell. Perhaps the bleakest scene I’ve ever witnessed. And yet, Father Rick caused me to see beauty in utmost ugliness. I hope you’ll stick around for the whole thing. It starts with a protracted setup, and then gets very intense. At the end of the piece, I will include a link where you can donate to Father Rick Frechette’s ministry. Perhaps the worthiest donation you will ever make, which I can say with total confidence, as I’ve seen what they do up close.

Here is “Love Among The Ruins”:

In the barbaric cave for the dead

Known in Creole as simply ‘mog’

My trembling hand blesses them

May the angels lead you far, far from here

And do so in all haste

You and this throng of dead that surround you

—Father Rick Frechette, from Haiti: The God of Tough Places, The Lord of Burnt Men

Port-au-Prince, Haiti

As disaster-chasers go, I’m pretty lousy. It’s ten days since the most catastrophic earthquake in modern history shook Haiti loose from its ever fragile moorings, yet the only disaster I’ve come near is at the Hartford airport in Connecticut. The iron-willed meter maid at the Continental desk informs me that Acts of Nature or God aside, my bag is 50 pounds overweight, and I’m going to have to dump provisions I’m carrying to Haiti.

Wishing to make my flight, I comply, muttering profanities as I hurriedly unload Clif bars, bottled water, and whiskey into a rickety box. As I do this, a band of ten or so curious Haitians watch my struggles, with their leader, an American Catholic priest of the Passionist order, Father Rick Frechette, looking on bemused.

“Everything alright?” he asks.

Though it’s taking me a while to reach the land of newly minted loss (in 40 seconds’ time, at least 230,000 Haitians were killed on January 12, one in every 50), I’ve come to Hartford to collect a man who, no matter where he goes, can’t seem to escape the dead. Father Rick, as most call him, has lived in Haiti for 22 years. He is founder and director of the Haitian branch of the international children’s organization Nuestros Pequenos Hermanos (“Our Little Brothers and Sisters”).

In the Tabarre section of Port-au-Prince, Frechette runs St. Damien Hospital, Haiti’s only free pediatric hospital. He also oversees an orphanage and the sprawling St. Luke missions, a boots-on-the-ground enterprise responsible for everything from its 18 simple street-schools in a country where fewer than 75 percent of children attend school, to running water and food to the city’s most ferocious slums.

Additionally, every Thursday—since long before the earthquake—Frechette and a band of Haitian volunteers trek to the city morgue and claim the nameless dead, who lie naked in bloated heaps on a blood-streaked concrete floor. “You’ve heard of Tuesdays with Morrie,” Frechette smiles, “this is Thursdays with the Krokmo” (a Creole pejorative term for undertaker. It translates as the “death hook,” meaning the show is over). The place is jammed and the dead often piled seven or eight high. The workers there are so inured to the stench and spectacle, that Frechette has seen a morgue attendant slaloming on roller blades around the bodies and workers eating their lunch while sitting on stacks of cadavers as though on breaktime in the office kitchenette.

In Haiti, even before the quake, dead bodies were nothing more than background music—as commonplace as they are unnoticed. If they didn’t end up in the stark death-cave that is the general hospital morgue, they were burned in the streets on the spot where they died (a pragmatic hygiene concern). The decency and sentimentality that a better-developed society affords are luxuries here. Father Rick and his men gather the bodies themselves, packing them into makeshift coffins fashioned from supermarket cardboard boxes. They then truck them outside the city, up a sun-bleached highway that runs alongside the Caribbean Sea, to the rolling wastelands of Titanyen, which translates from Creole as the “fields of less than nothing.” A New Orleans-style Haitian jazz-funeral band—all horns and drums—plays graveside. Father Rick, an irreverent sort, calls them “The Grateful Dead.” Then he and his men plant the cardboard coffins in large holes dug by their own gravediggers, endowing their cargo in death with a tiny modicum of the dignity that eluded them in life.

When I meet Father Rick in Hartford, he is torn between two families. In the quake, he lost about 10 people on his staff, with many more unaccounted for. Several of his missions are damaged or completely demolished. Many of his Haitian employees are homeless, living in tent cities in public parks. But he missed the quake itself and feels bad about it—a shepherd, he tells me, should ride such episodes out with his flock. And even though he rushed back to Haiti in the chaotic days that followed, he was forced to return to Hartford after several days to tend to pressing business stateside. His cancer-stricken mother was dying. He had to see her off, then bury her. She died shortly after he performed a bedside family Mass. The day I meet him in Hartford is the day after his mother’s funeral.

I first communicated with Father Rick over a year ago, itching for an excuse to profile him. It was a fight. Frechette is averse to publicity and would prefer to be left in peace to carry on his work. He seems happy when I joke that I’ll just call him “Father Bob” throughout this story. “Could you?” he honestly inquires.

From Hartford, we hit Newark for a lengthy layover and a connection to the Dominican Republic where a nine-hour bus ride to Port-au-Prince awaits us. (Only the military, humanitarian missions, and John Travolta, it seems, are being allowed to fly into the city airport.) By the time we reach Newark, Frechette is already frayed and distracted. With a ruddy tan, dressed in cargo pants and a North Face sweatshirt, he looks more like an athletic director at a good basketball college than a man of the collar. He prides himself on his unflappability but the tension is tugging at his face. Forever several hundred emails behind, Frechette’s now about 900 in the hole. He wants to work at them during the layover and suggests I talk to the Haitians who accompanied him back home.

I ask them as a group, “Who wants to eat?” One of them says, “I will.” I mistake Yvon for the English-speaker of the bunch, but it quickly becomes apparent that “I will” is the extent of his bilingualism. We tuck into a Naugahyde booth at the Garden State Diner for 30 minutes of awkward smiles and French fries. Yvon grew up in Father Rick’s orphanage, and his late father was a big houngan (voodoo priest). He’s now Frechette’s regular coffinmaker, but all of this I learn later, since we can’t understand each other.

Built like an NFL strong safety, Yvon is eating on my tab, but he politely orders a meager appetizer basket of chicken fingers. He eats half of them, then carefully wraps up the other half in a napkin. He starts to jam them into his pocket before I stop him and fetch a doggy-bag. I don’t need to speak Creole to understand what just happened. Yvon might be in the land of plenty, but he’s headed to a place where the next meal is never assured. In a country where, pre-quake, millions of poverty-crushed Haitians resort to eating mud-cakes mixed with vegetable shortening, a half-basket of two-day-old chicken fingers can seem like a feast.

After lunch, I take a seat at the gate with the other Haitians, all of whom work for Father Rick. Among them is a Haitian-born American, who prefers I call him “Johnny B. Goode.” He speaks perfect English, and translates, as undramatically as if he were relating a weather report, the horrors the rest have seen: the crumbling walls and lost relatives; the frantic digging of friends and family out from the rubble with forks and spoons; the sleeping in the road in shifts, one family member standing sentry against cars passing in the night.

Father Rick shows up at the gate shoveling down food-court Chinese, a last break from his rice-and-beans staple, which he sometimes varies with beans-and-rice. With 200 emails knocked out, he’s returned to the land of the living, only to tell me, in steadily unaffected yet gregarious fashion, more about the land of the dead.

He describes the pauper’s cemetery near the airport, where poor Haitians who can’t afford a burial plot rent one for deceased loved ones for four or five months. Then the gravediggers come, take you out, burn whatever’s left, and throw your bones against the wall, clearing space for the next tenant.

“There are voodoo rituals there all the time,” Frechette says. “Candles in skulls. Prayers to make the dead go cause a ruckus. We send our spirits up. They send theirs’ sideways to cause problems for others. We’re the Ghost Busters, they’re the Ghost Dispatchers.” He once brought an Italian visitor to witness the ceremony, and she became so freaked out, he had to give her his cross. He constantly comforts people by giving them his crosses. He fingers the one dangling from his neck now, saying it’s his 25th in six years. “I don’t buy ones I like anymore because I’m not going to have them for long.”

Father Rick’s Haiti is a place where the dead literally stick to you. Sometimes, his boots even stink of them. Here, he shows me, popping one off. There’s a faint whiff of his morgue travels and burials on his REI boot. “That’s really tame,” he says. “I washed these. They were so bad, I wouldn’t even tie them, just tucked the laces in.” When he has to take his shoes off at airport security, he says people wonder, “What’s the matter with that guy’s feet?”

He’s been doing the morgue runs for 15 years, but has never gotten used to the smell. It makes him so sick, he brings along rum and cigarettes. “People ask me if I smoke,” he says. “Only on Thursdays.” The Haitians avail themselves of the goods, but for Frechette, they’re not optional. Without the spirit’s fumes and cigarette smoke chasing the smell of the dead out of his nostrils, he vomits, which his Haitian colleagues find amusing.

When he returned to Haiti right after the earthquake, there was an overflow crowd at the morgue, literally thousands of dead laid out in the street in front of it. “They were picking them up with backhoes and bucket-loaders, dumping them into trucks,” says Frechette, adding that the machines crunched the bodies against the walls in order to be able to scoop them. “They were hanging out the sides like crabs in a bucket. Really, really terrible. It was so shocking, so disgusting, I yelled, ‘Give me a cigarette!’ ”

His Haitian right-hand and all-around fixer, Raphael—whom Frechette regards as something close to a brother—couldn’t find them. Frechette, now desperately gagging, was yelling, “Give me a fucking cigarette!!!” A journalist, taking in the scene, sidled up to him. “I heard somebody say, ‘I’m an ABC affiliate, and I’m wondering, are you Father Frechette?’ I said, ‘Do I look like a priest?’ I wasn’t going to be caught using foul language.” By the time the cigarettes were found, he says, it was too late. “I was empty of everything.”

Many of Frechette’s tales of the dead have dark punchlines. They put me in mind of Graham Greene (who had a pass at Papa Doc Duvalier’s Haiti, the “shabby land of terror,” with his novel The Comedians). Greene noted “that there is a delicate line between tragedy and farce,” and Frechette extracts plenty of farce from this tragic land, wearing it like a pair of floaties in a sea of roiling misery.

He knows it, too, and figures that second only to his faith in a God that orders the universe even amidst the apparent chaos, humor is his salvation. He tells me he read somewhere that a normal reaction to a normal thing is normal, and an abnormal reaction to an abnormal thing is normal. But a normal reaction to an abnormal thing is abnormal. Even so, there’s a “hierarchy of maturity,” he says. You can become a “psychological fetus,” upon witnessing horrors like Haiti’s, which makes you a burden to everybody, as the problem becomes comforting you. You can become angry, blaming everyone or everything. But the most productive abnormal reaction, he says, is to find laughter. He does that, he reasons, and it keeps him moving. And he always has to keep moving.

When I ask him how he could head back into the jaws of Haiti just a day after burying his mom, he tells me of her death. She knew it was happening, and she had time to prepare, had the best care, had lived a full life, and died with her family surrounding her. When he asked his mother why she wasn’t afraid, knowing she’d die, she told him that she “believes in God, and if she looks at the whole trajectory of her life, life has been very good, why start mistrusting it?” “I think the fuller your life is, the less death is a threat to you,” says Father Rick. “Empty people are scared to death to die.”

The end, he reminds me, comes for us all. “But for the difficult thing, the unavoidable thing, it all went right,” he says. “So you have to be thankful. ’Cause it doesn’t go right for most people on the planet. [The earthquake victims] didn’t have four seconds warning, had buildings thrown on top of them, were dragged out crushed, lifted up by bucket-loaders and thrown into trucks. And buried anonymously while everybody near them is retching, including me. It’s the wrong way. It’s the wrong way,” he repeats for emphasis. “So when all the unavoidable things in life go the right way, you should be grateful and see everybody’s not so lucky. That should make you engage, to try and make it go right for as many people as you can, you know what I mean?”

We touch down in Santo Domingo, and I take in the Taco Maker fast food, the cerveza signs, and the Ford Sport truck raffle at the airport. The Dominican Republic has all the taken-for-granted decadences of civilization: people holding hands on leisurely strolls down beachfront promenades, bicycling ice cream vendors, sidewalk cafes. The place we’re headed just a short while away has none. As a friend said to me before I left, “It’s as though God bisected the island of Hispaniola, and said, ‘This side gets the shortstops. This side gets the cholera.’ ”

With a group of doctors and missionaries headed for St. Damien Hospital, we board a bus that will drive us through the night into Port-au-Prince. Frechette rides shotgun, and I sit behind, coaxing stories out of him the whole night through. We get only brief fits of sleep and a few squirt breaks in the middle of the road.

Born in Connecticut to a father who was an engineer for Royal Typewriter, Frechette took a job after seminary in a Baltimore parish, where he did children’s Masses. Inheriting a modest animal act from the priest who preceded him, he strove to make it bigger and better, bringing in a live donkey for the nativity scene. He had to diaper it, after being told that if the donkey fouled the sanctuary, “I’d be transferred very fast.”

His great-uncle, a vaudevillian, helped him train animals to expand the repertoire. “I kept working on this dog/bird act,” says Frechette. “The dog was really well-trained. He brought announcements in his mouth at the end of Mass. But when he incorporated the Dalmatian and a white dove into an illustration of Noah’s ark, things went terribly wrong. The dove was supposed to fetch an olive branch. But when the dove came back and landed on the dog’s head with it, “he was eaten.” The crowd spooked the dog, Father Rick figures. It worked much better in rehearsal.

From Baltimore, Frechette went to Mexico to learn Spanish, so he could work with refugees in New York. There, he met the man who would change his life’s course from being a simple parish priest: the late Father William Wasson, who founded Nuestros Pequenos Hermanos (NPH) and ran a huge orphanage in Mexico.

Frechette first tried working with NPH in Honduras in the mid 1980s. But he wasn’t terribly enamored of the country’s political crosscurrents and felt he was getting pulled into things that were none of his business. “I had no idea about all these revolutions. The people would tell me priests and nuns were fighting with them with guns. It was a whole new world for me, I didn’t understand any of it.” Drawn to Haiti, Frechette was told by Wasson that if he was willing to go by himself and stay there, he was free to expand NPH.

“Being from Connecticut,” says Frechette, “Mexico was quite a shock. But Haiti was beyond words. The dire poverty. The filth. The chaos. Everything—it was a disaster.” Without knowing a soul, or even the language (he’s now fluent in both Creole and French, along with six other languages), Frechette planted his flag, started the orphanage, and buckled his seatbelt to hurtle full-tilt through 22 years of miracles and madness, which in Haiti, are often indistinguishable.

There was the flood which destroyed the town of Gonaives in 2004. During it, a drowning mother put her baby in a basket before washing away. He was found alive, and given to Frechette’s orphanage. They named him—what else?—Moses. But most of his stories come with less joyous endings. Many of them are touched upon in a slim, newly published collection of Frechette’s writings, the title of which belies the brutality and violence of the place he lives: Haiti: The God of Tough Places, The Lord of Burnt Men.

No one should think Haiti was done in by the earthquake. It’s a disaster of great magnitude, to be sure, but just the latest one. “You see it during a disaster,” says Frechette. “But it’s always a disaster.” It’s a place where the unemployment rate hovers around 80 percent, and over half the population lives on less than a dollar a day. It’s a place where mothers think that landing their child in an orphanage—where it’ll have shelter and three squares each day—is the equivalent of getting a scholarship to Groton. They will often come visit on family days, pretending they’re the children’s aunts.

It’s a place that, no matter which local or neocolonial interest gets its proxy seated in power, remains rampant with instability, violence, next-to-no public services and systemic political corruption. Graham Greene called Haiti “the nightmare republic,” and it’s seen 32 coups in a 200-year-history. Old Haiti hands don’t ask the question, “Where did it go wrong?” But rather, “When did it ever go right?”

Frechette can recount unspeakable atrocities. He has seen bodies being eaten by pigs in the middle of the street. He has seen a man roll around his half-dead wife all day in a wheelbarrow, after she’d been shot in the head, looking in vain for medical help. He has seen a severed head stuck on a post outside a nunnery, for no apparent reason. He has been shaken down to recover the remains of murder victims. He has seen his customs broker shot in the jaw. He knew a mother who took her epileptic son to a houngan, who poured lye on the boy’s head in an attempt to exorcise the evil spirit. The boy, whose burned skin turned him into an unrecognizable monster, seethed with hatred for the woman who only wanted to help him, until he went crazy and died.

Then there are the kidnappings—a robust industry in a country without many. One of Father Rick’s many sidelines is playing hostage negotiator. It’s a trade that chose him, not the other way around. Frechette’s missions provide all manner of services to Port-au-Prince’s sprawling Cité Soleil slum, which seems to have been named ironically as it is one of the darkest places on earth. About 20 minutes away from St. Damien, it is considered by some to be the most dangerous place in the world. Known for its grinding poverty and hair-trigger violence, it’s a place which U.N. troops go years at a time without entering.

But it’s also a place where Father Rick enjoys a fair amount of popularity, supplying the locals with everything from movie nights to rice and drinking water. He’s welcomed there like a hometown hero. Motorcycles ride alongside his tap-tap (the brightly painted, covered pickup trucks used as taxis and shuttles, where you tap on the side to have a driver let you off), with well-wishers calling “Mon père!” He is one of the few outsiders in good standing among the competing gang leaders who run the place. While I’m with him, one who escaped from the prison thanks to damage during the earthquake calls Frechette’s cell phone to offer condolences on the death of his mother.

With such good relations, Frechette will often get the call to go in and negotiate when someone like a foreign priest gets kidnapped—which happens with some regularity. At any time of the day or night, he might go nose-to-nose with gang leaders and the gun-toting child soldiers who do their dirty work. Not a macho type prone to losing his temper, he will nevertheless bark demands—“show teeth,” as he calls it—because they’ll cannibalize you if you display weakness.

But even his kidnapping stories come with built-in punch lines. There was the time he himself was almost kidnapped. He, Raphael, and an Italian doctor were driving home in their truck, when two kidnappers jumped out of nowhere with guns drawn. “I said, ‘Oh shit!’ The Italian doctor said, ‘What? You’re supposed to say Mother of God.’ ‘Yes. That’s next.’ First the human reaction, then the divine interpolation.”

The kidnappers were horrified when they realized they’d mistakenly tried to nab Father Rick. They begged him not to tell their leader, who Frechette says was regarded “as a Caligula,” one of the most ruthless gang leaders in Cité Soleil. Evans, as he was known, would’ve almost certainly killed them. They explained they only did this because they were hungry and wanted something to eat, asking him if he could spare a few bucks. “I said, ‘You’ve gotta be kidding! You scared the bejeezus out of us, and you want us to buy you lunch?’ ” He refused.

But the very next day, word spread that a young Czech priest had been kidnapped along with his truck. Father Rick went back to his assailants, apologized for losing his temper, and bought them rice-and-beans and beer. Then he blackmailed them. He told them he wouldn’t tell Evans of their mistake. “But you’re going to do me a favor, and I don’t care how you do it.” His deal: Evans had kidnapped his colleague, Father Roman, and in exchange for not telling Evans, they were going to do whatever it took to find the Czech priest and get him freed.

It turns out, Evans had decided Father Roman was worth $30,000, and if someone didn’t pay it, he would cut off his head. But, by the next morning, with Father Rick’s inquiries and efforts, Evans cut him loose for pennies on the dollar (he’d have probably turned him loose for free, Frechette says, but even kidnappers have some overhead—the safe house, the gunmen, etc.—and “people have to eat”). Evans gave back the truck, too. Father Rick makes sure to pay the ransom surcharges out of his own pocket, not asking family members for the usual $1,500 or so, so nobody can accuse him of being in cahoots and splitting money with the kidnappers.

Another time, he got the call to negotiate the release of a Salvadoran priest named Father Cesar, who’d been kidnapped. It was after dark, and, nervous about dealing with kidnappers he didn’t know, he convinced one of Cité Soleil’s gang leaders, Ti Blanc, to go with him. Acting on short notice, Frechette didn’t know the way, didn’t have any diesel in his truck, and didn’t have any ransom money. By the time the night was over, a muttering Ti Blanc had given him a lift, lent him gas, and fronted him the ransom.

But Frechette’s life isn’t all smiles and Keystone Kidnappers. One afternoon, he says, he was going to visit some nuns. On his way there, he saw a teenaged boy burning in the street. A group of thugs had set him on fire. He was already dead, and Frechette could do nothing for him, but he drove ahead and asked the nuns for five buckets of water. He went back to the scene, hauling eight of the sisters with him. They got out of the truck, took the buckets, and extinguished the flames consuming the boy’s body.

“I can still hear it. I can still smell it,” Frechette says. “The sizzle like frying steak.”

“Then we put him in the back of the truck, and do what we always do. Have a prayer right there. To make a counter-witness by our own behavior. The gang that set him on fire stood there and watched as we did these things.” His missions’ role, whether through doctoring or teaching, bringing food or burying the dead, Frechette has written, is to help “repair the damage done . . . to make grace present, concretely, in our world.”

Later, the mother superior called Frechette telling him a trembling, crying woman came to the sisters and asked for her. When she came outside, the woman fell to her knees and kissed her hands. The mother superior didn’t understand. It was the mother of the boy who’d been burned. Someone had run to tell her, “They’re killing your son and setting him on fire.” She raced out of her shack, and when she was within view of her son, was so horrified, that her legs froze. She couldn’t move them, neither to run toward him, nor to run away. “She was frozen in hell,” Frechette puts it.

She told the mother superior that she saw a truck go by, and then slow down, and then keep going. Then she saw it come back. And the people in it got out, and “put out my son like I was wishing I could put out the fire on my son’s body.” Then they picked him up until he was clean. Then they prayed for him. “Everything she tried to do was done in front of her, by absolute strangers who didn’t know her or her kid.”

Of all the emotions the woman was entitled to, he wouldn’t guess gratitude would be high on the list. And yet there she was. “It made her able to live with it,” Frechette thinks. “It’s like God sent someone to help her, like it restored her faith in humanity again. . . . I call it the countersign. The terrible thing that’s in front of you, you hurry, and offset it right away. Before what happens is too taxing and too poisonous. . . . Sometimes with horrible things, you really feel there is nothing you can do. Nothing. You’re just useless. But over time, you start seeing that to do the right thing no matter what has tremendous power.”

By morning, we’ve reached the large St. Damien complex in Tabarre. The earthquake has taken its toll here, just as it has everywhere else. Two of the compound’s four security walls have collapsed. The chapel, where Frechette conducts Mass every morning at 7 a.m. (before inviting attendees to follow him to a room at the hospital where he blesses the hospital dead from the night before) is missing stained glass and stonework. Sunlight hits the altar through a punched-out oval window that three angels on a ceiling fresco look down upon, as though dismayed.

Though a well-line was ruptured, leaving it waterless at first, the hospital is in pretty good shape. (The walls, though, bear magic-marker hashmarks across their cracks. If aftershocks cause them to shift, it’s a sign the building could fall.) There are scores of patients in tents and cots out on the lawn, as the 150-bed pediatric hospital is grossly overfilled with adults as well as children, since most of the local hospitals were destroyed. Many of the patients have been afraid to sleep indoors since the earthquake, anyway.

Frechette steps off the bus and is plunged back into his dizzying world. From staffing shortages (roughly 30 percent of his Haitian staffers haven’t returned or are unaccounted for) to where to put post-op patients to how to bargain for rice with the inflationary prices, he cannot walk ten paces down a hallway without being besieged by five new supplicants asking what should be done. He takes it all in stride, with a bemused smirk and crisp, clean, assured answers. He works long into the night. His dinner might consist of dipping crackers into a jar of peanut butter, maybe even while nipping at an end-of-the-day Prestige beer in his “office,” a table which four or so others are sharing at any given moment. It is exhausting to watch him work.

People tell me that while the quake has made things worse, this is pretty much Frechette’s life as usual. Robin Schwartz, who works at St. Damien, says he jokes that he’s “a priest who lives in the maintenance closet of a children’s hospital.” It’s not really a joke. He lives in a single second-floor room, which at the moment is packed with visitors’ suitcases. By these standards, negotiating hostage-releases may seem like a reprieve.

As Frechette is continually slammed with administrative duties, I spend a fair amount of time traversing his hospital, making the acquaintance of doctors and patients. Two of my favorites are my roommates from Scranton, Penn., Peter Cognetti and Scot McKenna, a family practitioner and plastic surgeon, respectively. In the no-frills bunkhouse behind the hospital, we sleep three to a room, a humid mosquito-ridden box with a sink that doesn’t work and a curtainless cold-water shower that is barely functional—though enough so that it is used by seven or eight other doctors who are sleeping on the breezier roof and have no bathroom at all. It’s, of course, vastly preferable to the digs of the million or so newly homeless in Port-au-Prince sleeping under squares of plastic in public parks. Nobody is complaining.

Like many of the volunteer doctors who swarmed St. Damien from as far away as Italy and Slovakia, Cognetti and McKenna arrived on their own dime with two big duffels and are returning to the States with nothing but what they’re wearing, leaving the rest, even their clothing, for needy Haitians. Cognetti also runs a personal philanthropic program. Before he left Scranton, friends and colleagues gave him piles of twenties, telling him to not to give the money to any organization, but to distribute it directly to Haitians.

Cognetti is like Sinatra at the Sands among the orderlies and patients. If you do anything for him—get him a Coke, hold the door open, turn on a light—you get a 20 dollar tip. His largesse gets us a much-needed fan, gets our shower nearly fixed, gets us cots. “What should I try for next?” he says, with mock greed. “Pay-per-view? A cash bar? Sean Penn’s gonna wanna stay here. Michelin will have to give us stars.”

Fraternizing with the docs, I hear about the horrors the earthquake wrought. In the early days, it was utter pandemonium—everybody out on the lawn, IV-bags hanging from trees, wounded getting carried in on planks of plywood, some so badly injured that their limbs would fall off when you’d lift them. With medical supplies short, stoic Haitians endured painful procedures on nothing stronger than Tylenol. The hospital was so short-staffed before international help started surging in that the Italian coordinator of surgery and the anesthesiologist would cover rounds during surgery.

All manner of improvised medical implements were used. Procedures were being done with un-sterilized power drills. Amputations were done with jiggly saws, which look like a piece of piano-wire with teeth. And there were a lot of amputations. Orthopedic surgeons were sawing limbs off some nights until 3 a.m.—an estimated 70 percent of surgical procedures were the removal of arms or legs. When I visit a post-op pediatric ward upstairs, six of the seven children I count are amputees, some of them double.

While it’s calmed down, the picture is grim. One of McKenna’s patients sits on a gurney, a young girl in a pretty Sunday dress, who calmly plays with her mother’s fingers. She looks totally normal, except for the huge flap of skin peeled off her forehead down to her skull. Nearly two weeks after the earthquake, a baby with severe burns on all four limbs, screams like she is on fire as her bandages are removed and her wounds cleaned. She’s been kicked to three hospitals and has only been given Ibuprofen for the pain. She repeatedly calls “mama, mama,” but only her father is there. She is so upset, she begins vomiting. With no nurse near and nothing to wipe up a mess with, the befuddled father simply cups his hands in front of her, letting his terrified daughter heave into them.

Everywhere you turn, it seems, there’s a new horror: the toddler found alive holding the hand of his mother, who lay dead beneath the rubble he was sitting on. The amputee mother I meet in the mini-tent city on the hospital grounds, whose young daughter cleans her wounds as though she is the mother now. The mother smiles and kisses me like I’m an old friend, though she doesn’t have much to smile about. In addition to losing her arm, two of her children were killed.

On the roof of the guesthouse at night, under a starry panorama, the doctors and nurses and humanitarian soldiers of fortune who populate such scenes (aid-organization do-gooders who’ve had their tickets punched in all the dung-heaps of the world) find solace in their cups, trying to make sense of what they’re seeing. They get serious. What’s going to happen when the rainy season comes—and it’s coming soon. Water will swirl all around the tent cities, where people are defecating on the ground. Many of my battled-hardened drinking companions predict that without proper sanitation, immunizations, and shelter, the disease outbreaks could make the earthquake look like child’s play.

A feisty Canadian nurse named Anne-Marie Gleeson tells me of pulling tent-city medical duty, where lines form around the block, patients lying about long-standing ailments, afraid that if they don’t make their troubles about the earthquake, they won’t get treated. “They’re in deep shit,” she says. “Figuratively and literally. I’m giving them 16 days of hypertension meds. But the rainy season is going to come and wash these people down a fucking hill. High blood pressure will be the least of their concerns. They’ll be drowning in mud and fecal matter. I’d like to think I make some kind of difference, but Jeez Louise. I can fix a broken leg. You have pus in your ear? I can fix that. But I don’t know how to fix a country.”

I meet a tent city habitué named Marc Andy Denard. A 33-year-old Haitian, he is trying to tend to his mother, who has a shattered femur. He begs me to take him to America, as though it is as simple as sticking him in my carry-on. He tells me he wants to be a refugee. Him, and several million others. It’s not going to happen, of course, but he’s so hopeful (and he has an aunt in the United States), that I agree to walk him to the U.S. embassy about a half a mile away, to see if anything can be done. We get there, and the Haitian guards won’t even let us in. Why would they? They have jobs and uniforms and a place to sleep at night (presumably). I’m told all inquiries will have to be made by phone, and nobody’s phone is working.

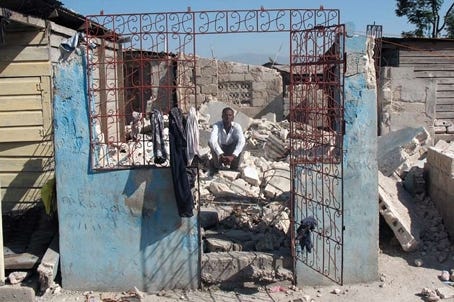

On the walk back, Marc tells me he’s afraid to stay in Haiti. “Here, the ground is very quick” he says, with a hunted gaze, “I don’t trust it. It feels it’s always trembling. I don’t know. It might be me. I have nowhere to go. Nowhere to live. My mother has feet break. Praise God for sending you to me. I’m sure if I’m with you, I become refugee.” I try to explain to him that it won’t happen. I don’t want him to harbor false hope. But he won’t listen.

Every time I see him subsequently, he’s wearing a blue blazer in the sweltering heat, which makes him sweat profusely. But he wants to look sharp in case he gets a refugee-status hearing. He seems to write all day. In the chill of the early morning, as I drop off food at his tent, he shakes off the cold with bleary eyes, wrapped in a blanket, and hands me pages, titled “News For The Media Of Matt Labech.” His written English is better than his spoken. He tells eyewitness tales of death and valor and fear. He uses, or misuses, words like “redoubtable.” He’s trying hard. As though if he writes well enough, someone will let him into America. I read his letters in front of him, clapping his back and telling him he’d make a fine journalist. He smiles sheepishly.

Life is no less dramatic outside St. Damien’s walls. One night, we find ourselves in front of the ruined cathedral, where Frechette’s friend Joseph Serge Miot, the archbishop of Port-au-Prince, used to preside. Miot was killed during the quake, thrown from his balcony and crushed. On January 6, Frechette says, Miot had asked him to call when his mother died. Miot wanted to travel to Hartford and perform the funeral. “He was dead before she was.”

As Frechette offers blessings and prayers for the archbishop and the others who died, two Italian journalists notice some dogs busy around a hole in the wall of the cathedral. They look as though they’re feeding, an odd sight in Haiti, since all the dogs here look like ribcages on sticks. We move to check it out. The dogs are feeding alright, on cadavers trapped beneath a collapsed wall—two, maybe three as someone spots an extra arm. The dogs have already eaten them down to their skulls, mats of hair collected on the ground in front of them. Father Rick shoos the dogs away, calls for the truck lights, and asks, “Does anyone have a cigarette?” He says a few extra prayers he hadn’t been counting on.

On another afternoon, I tag along as Frechette and a small group of doctors take the St. Damien tap-tap over to the slums of Cité Soleil to check on two of his street schools. The poverty almost hurts your eyes. Women wash themselves in water collected in potholes. Small children walk around naked. Buildings are pocked with bullet holes.

“Oh look, a chicken!” says a doctor from Slovakia.

“That’s a fighting cock,” says Father Rick, without batting an eye.

On the way there, Frechette regales us with kidnapping tales, like that of the elderly priest he freed, who didn’t take kindly to being grabbed. He scratched and bit his kidnappers and howled like a werewolf. When Father Rick came to pick him up, he was a mess. Frechette was outraged. “I said to the kidnappers, ‘You should be ashamed of yourselves. Look at him. He’s covered in blood.’ They said, ‘You think that’s his blood? That’s our blood!’ ”

But when we disembark, he is off like a shot, 30 paces ahead. Not only is he always a man in a hurry, but he wants as many people as possible to see him with the newcomers, so that they put together that the doctors and construction-types coming in over the next few days are with him. It’s an insurance-policy, he tells me.

Frechette is surrounded by neighborhood children. As I walk a fair distance behind him next to an open sewer, a 30-year-old Haitian man who speaks fair English grabs me. He wants to show me his ruined house, which is located down one of the tunnel-like alleyways of corrugated-tin-and-cardboard shacks that run like habi-trails throughout Cité Soleil. I catch the priest’s eye and motion that I’m making a detour. He nods, distracted. He doesn’t have time to babysit.

The Haitian’s name is Jean Yves Raitt. He has a wife and a 3-year-old son. The boy is naked from the waist down. “My house went down,” says Jean. “I have no shelter now. Livin’ in the street.” He shows me what was his place, all crumbled cinder. Now all he has is a tarp flap and a rug, his family sleeping next to the open sewer. As I take pictures of him and his boy in the ruins of their house, two other severe-looking Haitians come upon our scene in the back alley and start jabbering in Creole. My trouble-radar blips. With over 4,000 criminals on the loose from the destroyed jail, many of them from this neighborhood, kidnappings are booming. A foreigner got swiped just this morning.

I pretend to listen to Jean, but I’m actually intent on the Creole-speaking Haitians. I can’t understand a word, except one, which I hear clear as day—“kidnap.” I have no idea what context they’re using it in, or if it applies to me, or if there’s a Creole word that sounds exactly like it and means something totally different. But I don’t want to find out. “Say, Jean,” I suggest, “Let’s walk and talk.” I want to get back to my insurance policy, Father Rick. Jean, sensing my unease, says firmly, “I will walk you out of here.”

As we do, the other Haitians follow close behind. I turn around and address them, even though they don’t understand me. Their countenances seem to soften. Jean walks me back to the main stem. But Father Rick is gone. He’s hopped a motorcycle taxi back to the hospital, leaving us with Raphael and the tap-tap, both of which are about a half a mile up the road. I make the long walk to the truck, collecting more and more Haitian men along the way, about 20 in all. But there is no trouble, they just listen to Jean tell me his woes.

He’s a tap-tap artist, painting them for money. But now, that’s dried up, and he has nothing. When I ask him what he eats, he laughs. “Eat?” like that’s a luxury he’s forgotten about. He drinks two small packets of water a day. His baby is getting dehydrated. Two weeks after the earthquake, no aid has come. I want to help the guy. Since I can’t secure my belongings back at St. Damien, I carry all my cash in my cargo-pants pocket. But I know that in this crowd, with my ride halfway down the road, if I peel off 20 or 40 bucks, I’m going to have to keep peeling until it’s all gone. So I don’t.

I point to a sidewalk market right across the street, where some produce is for sale. I ask him why he doesn’t steal out of necessity. He shakes his head disapprovingly: “That’s not my way. That’s not my way. I’m praying for the help. And any help not coming. I don’t know what I’m gonna do. I want my country changing. I don’t have anything to give my wife, anything to save my life. Everything is broken.”

Whenever Father Rick can shake the shackles of administrating, we shoot all over the city. By day, we take motorcycle taxis, Frechette’s preferred mode of transportation, as it’s faster in the punishing traffic, and feels freer—something one suspects with all his responsibilities he doesn’t get to feel often enough. It also gets the blood going. During a long motorcycle trip one afternoon, my driver and I almost get dislodged by a guy swinging a long piece of lumber, by a protruding tap-tap side-mirror, and by a mob of 100 or so Haitians running directly at us, afraid cops were about to shoot them as they looted. (Though “looting” is a strong word for standing over crushed buildings, breaking concrete apart with pipes, hoping you can find a little scrap rebar to sell or prop up your tent.)

Sitting on the back of a tap-tap, watching the city go by at night, is even eerier. With the dark cloaking any color that would stop your eye, you simply see the creepy contours of destruction. Block after block after block of ruin. Collapsed second floors smother first floors like cheese on a lopsided tuna melt. The air has a constant acridity.

I ask Frechette if I’m smelling remains.

“Nahhhh,” he laughs. “It usually smells that way. The sweet smell of old piss!”

It does smell like stale urine, he’s right. But also of dust and crumbled concrete ash and fire, as people burn trash in the street—not in receptacles. There don’t seem to be any. Instead the street is one giant ashcan, and everything in it seems to be considered kindling.

Half-wrecked buildings tilt at odd angles, looking ready to fall from the push of a hand. Though there are no streetlights, no light at all except for those of passing cars, everyone is out on the streets. They are jam-packed. Like a giant block party without the party. People sit defeated on coolers. Men push wheelbarrows full of sticks. Squatters sprawl in abandoned intersections as if sitting on park benches. Pedestrians walk and walk and walk in the pitch dark, with no apparent destination. Trying to go somewhere. Trying to pretend there’s anywhere to go.

Families bed down for the night in the street with cinder block barriers that they hope signal cars not to run over them. Some seek extra protection setting up between two cars, as if they’re parallel parking their children for the evening. There are no beggars. What would be the point? Nobody has anything to beg for. Even though I saw the pictures before arriving, even though I’ve been to other third-world cesspools and New Orleans after Katrina and even the east side of Detroit, I have no frame of reference for what I’m witnessing. The best I can come up with is Cormac McCarthy, who unwittingly offered a dead-on description of this scene in his novel The Road:

Wearing masks and goggles, sitting in their rags by the side of the road like ruined aviators. Their barrows heaped with shoddy. Towing wagons or carts. Their eyes bright in their skulls. Creedless shells of men tottering down the causeways like migrants in a feverland. The frailty of everything revealed at last.

The only difference being McCarthy had to imagine his post-apocalyptic world. In Port-au-Prince right now, he wouldn’t have to imagine a thing.

My tour of hell continues one afternoon, when several of us take motorcycle taxis out to the fields of Titanyen. Father Rick needs to check on his gravediggers’ progress for burials the following day and also wants to see about the rumor that bodies are getting dumped.

We head out of the city toward the low-slung mountains, then shoot up the coastal highway. The sun scorches us, as we look off to the west, the blue-green Caribbean shimmying with blithe indifference toward the wrecked country that its surf crashes upon. When we get to Titanyen, we have to get off the motorcycles and walk them over a huge dirt berm, seemingly erected overnight. Frechette suspects someone wants to keep people out. Back on, getting caked with dust as we bump up and down the gulch-riddled dirt roads, the hills are literally on fire—little brushfires all over the place. I tuck my head behind my driver’s shoulder, trying not to catch flying embers in my hair. At first, I think it’s some kind of controlled burn. Then I remember I’m in Haiti. Nothing’s ever under control here.

As we near Frechette’s graveyard, the rumors prove true. There’s a stack of half-plowed earth, atop which lie 30 or so naked bodies, as if a bulldozer driver started to bury them, went on a smoke break, then forgot to come back. Arms and legs jut from the half-dug earth, like some sort of Goya-esque horror, while the bodies on top of the pile are so sun-baked, their skin looks like plum pits. The maggots are feasting.

For a while, we wordlessly survey the disgrace. Then Father Rick looks up to the burning hills. “Just like hell. Isn’t it?” he says. “It always amazes me how nature aligns.” The state has been doing mass burials here since the earthquake. But even before, Frechette explains, “This whole area was known as the place of the dead. For 40 years, since the time of Papa Doc, it’s the place where they dumped the dead. It’s notorious for executions, for emptying the prisons out by bringing them all here, digging a hole, having them stand at the edge, plugging them in the head, then letting them fall right into the grave. We use the same areas to bury the dead in the right way.”

A little ways down the road, sweat-drenched men with pick-axes and shovels stand in huge holes, readying them for tomorrow’s burial. Cows graze in a field of white wooden crosses. Frechette’s had to stop using them, however, since people would steal the crosses to cook with. He’s now switched to smaller crosses made of fish-tins, hiring crossmakers from Cité Soleil. Though even that is getting too expensive with all the newly dead.

Our motorcyclists nervously call for us to leave, before the flames jump the road, and we have to ride out through a tunnel of fire. On the way back up the hill, I step in a sinkhole on a grave, and nearly go down. Father Rick laughs. He says it’s seven years bad luck to step on the dead, seven years good luck to bury them. “I could have a square-dance here,” he says, “and mathematically, I’d still be ahead of the game.”

Then his smile fades, and he looks puzzled. “We’ve buried over 10,000 people here. I don’t think I know the name of even one.”

The next morning brings the grimmest business of all, pulling bodies out of the morgue. A Haitian morgue is not a morgue as we understand one. There’s no embalming. No stainless steel drawers. No clean white sheets. No air-conditioning. Instead, the dead are thrown into heaps in spottily-refrigerated rooms (the generator kicks off even while we’re there, and when it stays off, Frechette says there are maggots up to his ankles). The walls are chipped. The ceiling tiles peel from water damage. The cement beneath our feet is grimy with dirt and dried blood and looks like a slaughterhouse floor. However the dead come in is how they stay—gashed and cut, shot and crushed, disrobed and bloody and bloated. Most people don’t know their dead are here, and never will. Even if they did, it’s hard to imagine recovering your loved one under such conditions, getting a morgue worker to let you in with a flashlight, kicking other bodies over, hoping to find your daughter or son or wife.

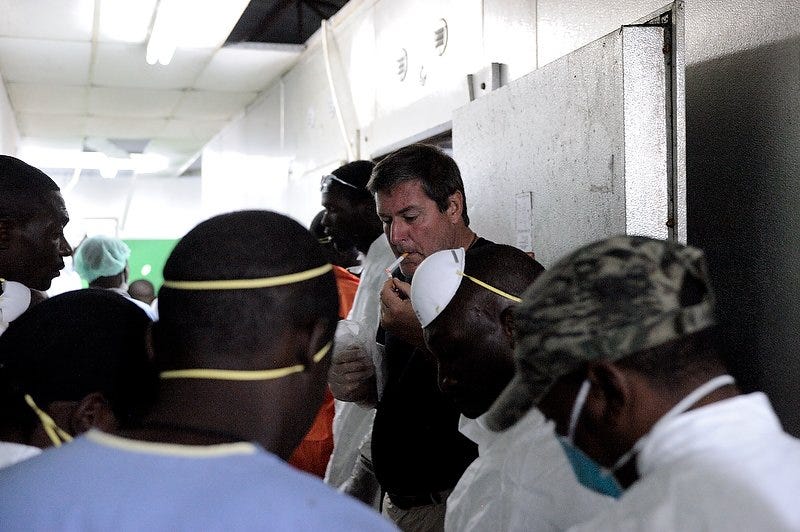

Father Rick, in cargo pants and Jesus-sandals, heads in with his 20 or so Haitian volunteers in protective plastic suits. They have come fully armed with seven trucks. They have only 20 cardboard coffins (there’s a shortage) but clean white canvas body bags that look like funeral palls will work for the other 150 or so. To kill the smell, they also bring Marlboro Reds and two bottles of three-star Barbancourt rum. “Three stars for funerals, five stars for weddings,” Frechette cracks.

They take their places in the morgue’s dark narrow corridor, a bucket brigade for the dead: lifting them, lowering them, sliding them, and then relifting them into the trucks outside. A couple Haitians pull the dead out of the cooler. The rest slap a coffin or body bag down, throw rosaries in, and place in them a white paper sheet, like those that come with your dry cleaning, which have imprinted on them “In paradisum deducant te angeli”: “May the angels lead you into paradise.”

Father Rick stands right next to the cooler, saying blessings. So as not to start vomiting, he smokes cigarettes like he’s trying to break his lungs, sometimes lighting up another while the first is still burning. He holds a roll of paper, the kind doctors place on their examination tables. And he rips sheets off with mechanical regularity, handing them to the Haitians after each of the dead they lift. After years of experience, they’ve learned that if you wipe your surgical gloves after each lift with the paper, the gloves last longer.

I stand beside Frechette, watching the dead get dropped into their body bags, sometimes hearing the thud of a skull on the floor. With so many people to move, the Haitians work fast. As they slide right past my feet, I clinically document all the variations: the contusions, the lacerations, the bloating, the exposed bones, the emaciation, the heads sitting on their necks at angles that necks don’t permit. I see just about everything, except gray hair. Not a one has gray hair.

As I watch this, I carry on conversations with Frechette and others. It’s a horror, to be sure. But it’s like I’m watching a movie. Taking Frechette’s abnormal-situation lesson to heart, I look for normalcy. I admire the perfect smoke-rings blown by Johnny B. Goode. I elbow Frechette when I spy one of the volunteers who is wearing an orange prison jumpsuit. On the back of it, in English, reads “Department of Erections.”

The dead just keep coming, and they come out gleamingly slick, like rotten vegetables left too long in a refrigerator drawer. Some of them are so drippy that the Haitians have to double bodybag them, as your cashier would leaky ground beef at the grocery store. I think it odd that I’m getting through this without feeling much of anything beyond sympathy.

But that’s when the kids start coming out.

They’ve saved the coffins for the kids since, depending on their size, you can fit five or six in one (a harsh necessity). I am still clinically documenting, but the things that didn’t bother me much before, all of a sudden do. My eyes start burning. I feel like I’m growing a goiter in the back of my throat. I hadn’t bothered with a mask or smokes, but the smell becomes excruciating, like that of a curdled-dairy factory. I ask Raphael for a hit of rum. He holds it two inches above my mouth and pours. I’m grateful for the stinging in my throat. I take the excess runoff, and rub it under my nose.

I watch the little ones go—a small girl laid on a longer girl’s legs, and then another added, and then another—and they all fit into a coffin no wider than a foot. As I take this in, Esther, the young Haitian woman beside me who is throwing string rosaries into the coffins, begins singing, temporarily hushing the Haitian men, who were feverishly barking orders at each other. It’s a clear, soulful Creole lamentation. As I watch the stacked babies slide past my boots, I hold onto her voice like a life raft. It’s the saddest song I’ve ever heard.

With the trucks loaded, we head back to Titanyen, the Fields of Less Than Nothing. The fires are out, but other journalists have discovered the place. Photographers take pictures around yesterday’s stack of unburied bodies. About six gigantic pits have been dug to unload the dead into. When our trucks arrive at the graves, Father Rick is bothered by all the extra cameras. “This turns it into something else,” he says.

He must proceed anyway, throwing white vestments over his dirty cargo pants. The brass band, The Grateful Dead, are posted graveside, looking rather ungrateful. We’re three hours late, and they’ve been standing in their black suits in the hot sun in these arid scrublands. But they strike it up anyway, playing “I’ll Fly Away” and “When the Saints Go Marching In.”

Even in his priestly garb, Frechette assists the Haitians in carrying the coffins and body bags to their graves. He doesn’t believe in asking people to do anything that he won’t do himself. I watch Raphael and Fred descend into the pits, to receive the dead, and align them. Fred is a gravedigger and an ex-con who grew up in Frechette’s orphanage.

Several nights earlier, we all went to Harry’s Bar, after Frechette had visited his old wrecked hospital, where a young woman and a volunteer’s visiting brother had died. “I could use a gin and tonic,” he said. Once at the bar, Frechette fell into conversation with another missionary, trading dengue fever and malaria stories. “This is what happens when missionaries drink,” he warned.

But with Johnny B. Goode translating, Fred told me a story of his own. A few years ago, he was to bury a little girl, and her mom was riding to the cemetery with him. When they got there, a Cité Soleil gang greeted him with guns, kicked the mother out of the truck, firing shots over her head to make her run off like a scared rabbit. They kidnapped him, but when they brought him back to headquarters, they realized they’d just kidnapped a dead girl as well—they hadn’t noticed the coffin in the flatbed. Not an ideal ransom scenario.

So they kept his truck and turned Fred loose, telling him to take the dead girl with him. Which he did. He threw the little girl’s undersized coffin on his back, and avoiding a well-known vigilante cop whose car he saw, carried her all the way back to the cemetery. I asked him why on earth he didn’t just leave it and run. He said he couldn’t, he owed it to the mother.

Father Rick, hearing the story, broke in, saying that afterwards, he found Fred in the crushed hospital that we had just visited. He was sobbing like a baby. “I couldn’t stop him,” says Frechette. “I said, ‘What’s wrong?’ Fred said, ‘The thing that bothers me most is that the mother doesn’t know that I fulfilled my pledge to her, and that I buried her child tenderly.’ He knew her love for the kid, and he had to carry her love for her. And he did it. You see why I do these things? In the most horrible situation, an ex-con kidnapped by the most brutal of thieves, stealing a corpse and chasing the mother off with guns. . . . Do you see the goodness that came out of it? It’s unbelievable, isn’t it? It’s unbelievable.”

There are no mothers graveside today. These are the nameless dead.

Haiti might be the only place where death with dignity entails being buried five-to-a-cardboard coffin. But it is moving and beautiful. Yet, I suggest to Frechette, it seems futile. Why do this? However horrible their lives were, this isn’t going to change that. Why spend so much time and energy serving people who’ll never know they’ve been served?

Frechette thinks about it a long while, then says, “If the dead are garbage, then the living are walking garbage.”

I watch Raphael and Fred working down in the pits. In the heat, they look like they’ve gone for a swim. Their close-cropped hair turns chalky white from the loose dirt falling in around them. They come out of the pits, which are so deep, they need running starts up the sides, and then have to grab someone’s hand above ground to pull them all the way out. Father Rick, his vestments stained with dirt and sweat, takes a spot above the body bags and cardboard coffins. There, he offers the last words these forgotten souls will ever have spoken to them:

The evening has come. The busy world is hushed. The fever of life is over. And your work on earth is left undone. In His great mercy, may God give you a safe lodging, a holy rest, and peace at last. May their souls and the souls of all the faithful, departed to the mercy of God, rest in peace.

(Editor’s Note: To see more of what Father Rick Frechette and his colleagues at the St. Luke Foundation are doing, go here, and to make a (tax deductible) donation, go here.

Bonus Track: Here’s a 2001 crusher from Justin Vernon, who you might better know as the brains behind/frontman for Bon Iver. And here, you won’t recognize him without his trademark falsetto. Like the story above, it’s a long song. But well worth your time, with haunting fiddle and piano kicking in by the end. It’s called, “When It Rains Down Here.”

Great stuff Matt.

I’m just going to share the two things that spoke to me recently:

“I was a stranger and you did not welcome me.”

And

If your country is getting booed by the nicest and most polite people on earth, maybe you should consider not being the kind of country that gets booed by the nicest people on earth.

I have a busy day so I'll have to leave "Love Among the Ruins" for tonight. I don't believe in gods but I do believe in the importance of serving our fellow man. So before I jump into my day this stone cold atheist will first send some coin to Frechette.

It occurred to me this morning that our nation faces a total absence of actual leadership. Most of our 435 congresspersons and 100 senators know right from wrong, have at least a rough understanding of American history, and are aware of their role as defined in the Constitution. Unfortunately, rather than leading their constituencies they choose instead to either pander to their basest passions or shrink away in cowardice and revulsion. Go along to get along. And to get reelected. The oligarchs are going to run things now so best to cling to their coat tails, the better to pick up any loose change that might fall from their pockets.

How quickly they flocked to this anti-Christ and without even a hint of embarrassment. Clearly these men and women are the cream of the American crop, the embodiment of American exceptionalism.

Compare and contrast this pool of pathetic mediocrity with Rick Frechette or Jose Andres or, for that matter, Volodymyr Zelensky.