Author’s Intro: The photo above is a bit of a head fake. This column is not supposed to be about Franco Harris, the Steeler great who just died at age 72. As promised right before Christmas, I’m running a New Year’s Day piece that I wrote seven years ago, one about the famous dead who won’t be coming along into the new year – what they mean to us, and the void that their clocking out leaves.

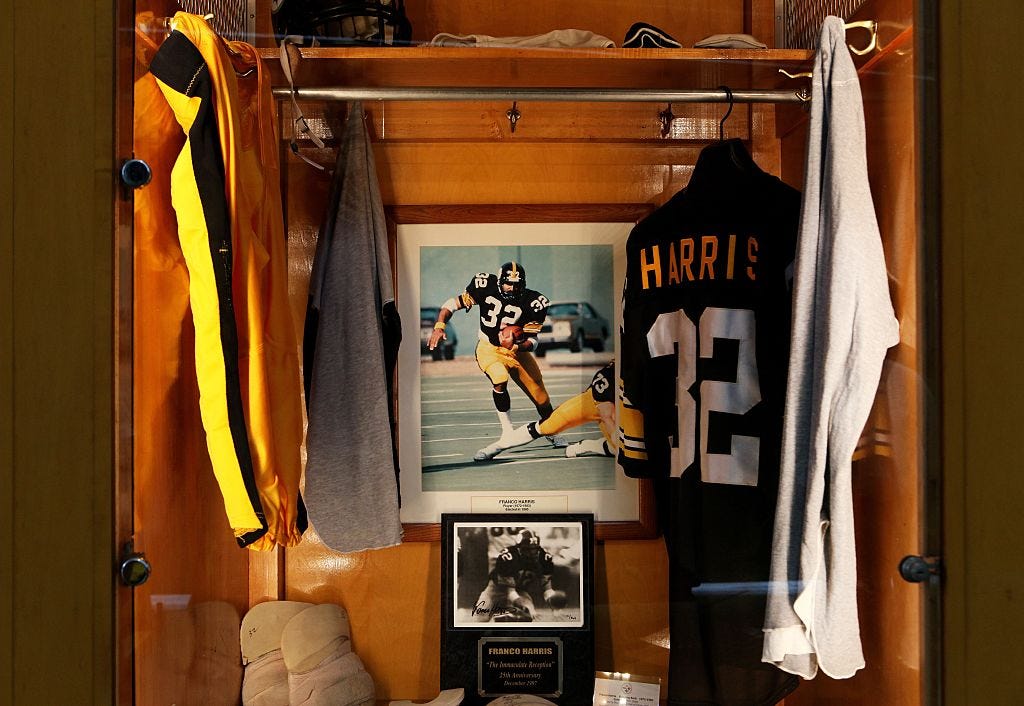

So though it’s a yesteryear piece, it felt appropriate to kick it off with a photo of Franco’s locker, since his loss is still fresh. As an Air Force brat who spent a large chunk of childhood in San Antonio, Texas, I grew up a Dallas Cowboys cultist. Though my parents – both born and raised in Pittsburgh – were diehard Steelers fans. So though we enjoyed resenting each other, I had a grudging affection for the Steelers, who were an easy team to love as you pretended to hate them for appearance’s sake. Truly hating the Steelers would be like hating my parents, which I wasn’t prepared to do, at least not until my teens.

One of the happiest days of childhood, in fact, came after my dad had moved us to Germany on a three-year assignment. As we were shipping out, we stopped off at my grandfather’s house in Pittsburgh. He let it be known that he lived across the street from an equipment manager for the Steelers. Though I barely watch football these days, I was an utter fanatic back then. I lived and breathed it. It was all I really cared about besides collecting swimsuit photos of Farrah Fawcett Majors. And so I was shameless in begging him to hit up his neighbor to secure me Steeler autographs. I gave him a wish list. My PapPap, as we called him, was noncommittal – he seemed somewhat embarrassed by the request. And then we moved to Germany, and I didn’t think much more of it.

One afternoon, several months later, a large box arrived, expertly packed. PapPap was an ex-Navy man – he’d dropped off the troops who stormed the beaches at Normandy - and he packed a box as meanly and cleanly as he made a bed or tied a clove hitch, all tucked corners and squared-away orderliness. My fourth grade hands opened that box, practically spasming with excitement, as I separated the individualized cardboard dividers lined with tissue paper to keep the signatures from smudging. There was one autographed photo after another of every meaningful Steeler legend from the era when they were most legendary, winning four Super Bowls in six years (and beating my beloved Cowboys in two of them). Both then and now, it was the very best gift I’ve ever received.

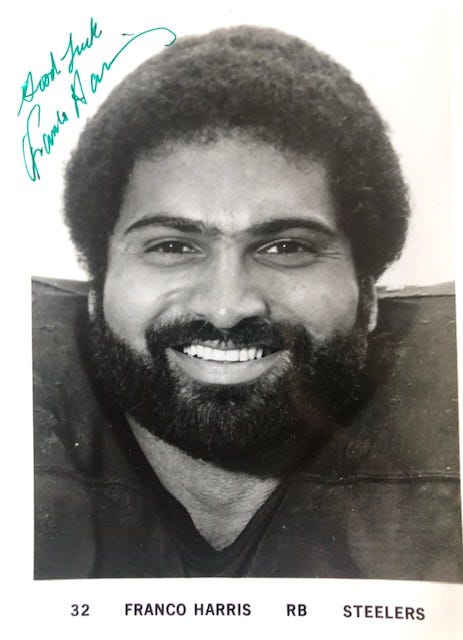

There was Mean Joe Greene, and the Jacks, both Lambert and Ham. There was Terry Bradshaw and Rocky Bleier and John Stallworth and my second favorite player of all-time, Lynn Swann, the Baryshnikov of aerial acrobatics, who ranked only behind my other favorite wide receiver, the Cowboys’ Mr. Clutch, Drew Pearson. (Both Swann and Pearson, fittingly, shared a number – #88.) And then there was the great Franco Harris. At the time I received this package, he was the career rushing leader among active players. (He’s currently 15th, but when he retired in 1984, he ranked third place all-time, behind only Walter Payton and Jim Brown.) I’d always heard Franco was the nicest of guys, something his obituary pieces validate in one anecdote after another. But back then, my nine-year-old self could actually smell the niceness on him. All the other legends just signed their names. But Franco signed his, “Good Luck, Franco Harris.”

I didn’t mind telling the snot-nosed punks I played sandlot football with that Franco Harris had just wished me good luck. Which felt like pretty good luck in and of itself. As someone who by disposition and for professional reasons, can often see the dark side of anything, I kick a lot of gift-horses in the teeth. But I try to leave good luck alone when it shines itself in my direction.

My grandfather is long gone. So, of course, is childhood. And now Franco Harris, a part of that childhood and my grandfather’s connection to it, has left the building as well. These are easy things to miss. But at least I’m not missing good luck. Not yet, anyway.

So maybe this intro was a not-so-mini piece about Franco Harris. Below is the photo I received in the mail that memorable day back in 1979. I still keep it in a folder on a bookshelf, instead of in a box in the basement, so that it doesn’t get nibbled by mice. And beyond that is the piece I promised/threatened to run, followed by some New Year’s musical picks you might want to listen to as life enricher/hangover remedy.

.

I've never been one for elaborate New Year’s rituals. I don't thump the walls with bread to rid the house of evil spirits, as some do in Ireland. Nor swing caged fireballs around my head to torch last year's misfortune, as they do in Stonehaven, Scotland. I don't make hollow resolutions, since I might fail not in expected ways, but in spectacular new ways yet to be imagined.

If Christmas is about giving, New Year's is about taking. So come New Year's Day, I take a fistful of ibuprofen and a nap. Then, after coming to, I take mental inventory of the old year's final moments, praying it was my wife I goosed as the ball dropped, since a sour-mash fog leaves me easily confused, and all white people start bearing strong resemblance.

There is one sacred ritual, however, that I observe every new year: I read about dead celebrities who didn't manage to escape the old one. In memoriam columns and slideshows make great clickbait, so by January 1, they're featured by every other news outlet. I read them all, to see who I missed and will be missing. It's not that I'm a celebrity worshipper; far from it. It's more that I can truly appreciate them once they've taken leave, much as watching an obnoxious child sleeping endears him. We all become innocent when we dream or die. And whatever you envy celebrities for in life—their fame, their fortune—you wouldn't switch places with them now. Death is the ultimate democratizer.

We lost many last year, too many to name, since even as the herd-of-the-famous is culled, they seem to multiply faster than they subtract. The Onion once ran a headline that nicely captured the faux-celebrity produced by wall-to-wall reality shows and YouTube suckerfish: "32 Percent of U.S. Citizens Still Not Famous." Decades from now, it is not hard to imagine entire memorial columns being taken up solely by Kardashian offshoots—their sex-tape costars, their baby-daddies, their collagenists.

And yet we lost some real stars as well. The replaceable irreplaceables. It was a bad year for musical Kings, as we lost B.B. and Ben E. It was a bad year for the sports/animal kingdom, as we lost Jerry "Tark the Shark" Tarkanian, Ernie "Mr. Cub" Banks, and Ken "The Snake" Stabler. I likewise seemed to have lost half my childhood television family: no more Dick Van Patten (Eight Is Enough) or Al Molinaro (Happy Days) or Wayne "Trapper John" Rogers (M*A*S*H).

On a more personal note, I lost NBA great/Chairman of the Boards Moses Malone. When I was a ballboy for the then-Washington Bullets in the '80s, Malone once gave me a surly look, then threw a bloody Band-Aid at my head—or "passed the torch," as I related to my high school basketball team, where I played twelfth man. And there went Jethro Pugh, who was not the most famous member of the Doomsday Defense. He wasn't even the most famous Jethro—he was no Cousin Jethro or Jethro Tull. And yet, when I was a second-grader growing up in Texas, I looked at his face every single day, since he adorned my wall when my world seemed no bigger than the 1977 Dallas Cowboys.

And while I wasn't looking, there went the New York Times's David Carr, one of my earliest editors and friends in Washington. An eccentric parade-float of a man, Carr, who had given up the sauce years ago out of necessity, was one of the rare souls who could blow into town, sit at the bar all night, and nurse Diet Cokes while still seeming to be two drinks ahead of you.

We lost a lot more. There will be no more Anita Ekberg seducing Marcello Mastroianni in the Trevi Fountain. There will be no more Cynthia Robinson, Sly Stone's funky horn player, imploring, as she did in "Dance to the Music," that "all the squares, go home." There will be no more Rowdy Roddy Piper, the most entertaining wrestler of all time. He lost partial hearing after his eardrum was ruptured in a dog-collar match. But he never lost his ear for perfect dialogue: "I came here to chew bubblegum and kick ass. And I'm all out of bubblegum."

These people weren't the poles of my life, just the random stars who briefly illuminated it. Which is what stars do, helping us pass the time, until our own time has passed. Noting their endpoint is the least we can do, a favor returned. For as Yogi Berra said, before we lost him last year at age 90, "You should always go to other people's funerals. Otherwise, they won't come to yours."

New Year’s Bonus Tracks: Those in the musical know might have detected that I lifted the headline of this piece from The Mountain Goats song, “This Year.” Here’s a live rendition of it that I particularly like. While watching it, I key in on the drummer. The drums are too loud here, as they should be. The drummer, Jon Wurster, is a comedy writer/performer in his spare time. As he should be. Life is dark comedy, and Wurster looks and plays like he’s in on the joke. The song’s lyrics, of course, help that along: I am going to make it through this year/ If it kills me. Even if the story ends as most things do (badly), for my money, it’s one of the more joyous and defiant statements of pessimistic optimism ever recorded.

This is Otis Redding and the Queen of Memphis Soul, Carla Thomas, dueting on “New Year’s Resolution,” recorded the same year Redding died in a plane crash (1967). It’s a song about putting things right. And it’s hard for things to go wrong when you have Booker T. Jones, Isaac Hayes, Steve Cropper, and The Memphis Horns playing behind you.

Happy New Year Matt - thanks for building this neat little community. I’ve slowed up on the commenting but still read most of what other people write.

While just about every other site eventually becomes infested with various species of online discourse mosquitoes, Slack Tide remains a beautiful screened porch on a cool evening. The mosquitoes rarely make it in, but on the rare occasions where they do I love the satisfying crackle as you jump into the comments to guide them towards the bug zapper.

Prose poet Matt,

I'm laughing and crying,

grieving and celebrating.

Ready now to launch my new year,

blessed and fortified

by your powerful remembrances.

Your heart holds the dead

and the living

with equal tenderness.