One Nation, Under Lunacy

And how a strange book by Nick Cave restored my sanity (this week, anyway)

I don’t know if you’ve noticed — and I don’t wish to alarm you if you haven’t — but our country has gone mental. If you yourself are a crazy person who takes umbrage at my use of “mental” as a pejorative, I’m not trying to gratuitously insult you. I’m merely observing that you happen to have a lot of company these days.

Why, just this week, I logged on to the trusty Drudge Report, as I’ve done for the last three decades. Not because Matt Drudge occasionally links to our humble little site, but because he selflessly brings The Apocalypse to me on a daily basis so I don’t have to waste time looking for it. Instead, I can dedicate the bulk of my hours to worthier pursuits like procuring weaponry, hoarding survival food kits off of paranoid Patriot sites (I can’t wait to dig in to “Ma’s Homestyle Chili Mac” – which allegedly won’t spoil for the next 25 years), and training my fists of fury to become maiming machines. Which I will likely employ on behalf of whichever side I choose to sign on with in the coming civil war — most likely, the winning one. (Everybody loves a winner.)

But back to us having gone collectively insane………I learned this week, in my readings, that some demented maniac beheaded his own father in their mutual home while still having the presence of mind to perform an anti-Biden rant on YouTube. (If he hadn’t been taken into custody, he’d probably already have a primetime Newsmax show.) Meanwhile, online world is presently arguing — as is their 24/7 custom —whether he was a Trump supporter. (There’s some evidence he wasn’t — fingers crossed, RFK Jr. stalwarts!) But even ISIS-like domestic snuff films might not be as troubling as MAGA rap battles, broader crimes against both music and humanity. A country that makes Ben Shapiro’s hip-hop single the number one song on iTunes can no longer claim sanity with a straight face.

Also, I learned that my old rightist homeyz have now declared war on……..Taylor Swift? And her NFL boyfriend? And on the Super Bowl, which used to be the one television event that could still unite America, but which is now purportedly a PSYOP to make Trump lose the election? This, according to people who’ve gone nuttier than a Stuckey’s log, or who are cynically pretending to be in order to appeal to all their viewers/social media followers whose cheese has truly slid off their crackers.

And then of course, Sesame Street’s own Elmo made the mistake of Xittering, Instagramming, Threadsing and Facebooking (social media is exhausting, even for hand puppets) the following innocuous question: “Elmo is just checking in! How is everybody doing?” For which Elmo garnered 205 million views on Elon’s Conspiracy Emporium alone. With many pouring their hearts out to a furry red Muppet who — spoiler alert — isn’t technically a living being. But why should that stop anyone? Nothing seems real these days. Need our confessors be?

My personal favorite reply came from “7/11 Truther”:

Wife left me

Daughters don’t respect me

My job is a joke

Any more questions, Elmo??? Jesus, man

It’s all kind of dispiriting. Making you pretty much want to drop life and go fishing. Which is admittedly my default reaction to most unpleasant stimuli. But which isn’t the best option during the frigid days of February. When I show up at ye olde bass pond, fly rod in hand, I can almost hear the fish saying, as they sulk on the bottom, uninterested in expending feeding energy: “Why are you here? Have you been reading the Internet again? Come back in mid-March, then maybe we can talk.”

So instead, I’ve been steaming lately as a sanity-saver. Not “steaming” as in ferociously brooding after being insulted in my comments section. But as in hitting my new portable steam room, trying to sweat out all the toxins, physical and otherwise. After sending Jeff Bezos a few hundred ducats (poor guy could use the money, his Washington Post is falling apart), this handy contraption arrived at my door. It might look a little ghetto, and the yoga-pant’ed model does not come with it, nor is she sold separately. (Probably just as well, my wife would’ve made me return her.)

But after heating it up for 20 minutes or so, it gets as hot as any resort hotel steam room I’ve ever been in, with the added benefit of there not being any naked Germans in it. Not that I have anything against naked Germans. At least not the ones who look like Heidi Klum. But they never, ever do. It’s usually an old prune named Gunther whose only hobbies — besides going on perpetual vacation — include carb-loading and manspreading, as he puts the giblets on display while you’re innocently trying to work up a shvitz.

But for me, it’s become a purifying near-everyday interlude, a ritual embraced by everyone from the Finns (who regularly score highest in national happiness surveys, no doubt because so many of them subscribe to regular saunas), to our Native American friends, who believe in the healing properties of the sweat lodge, and think of it is a window on the divine. I don’t know about all that, in my case. But within five minutes of entering — with the 100 percent humidity enveloping me — I sweat harder than Nancy Mace when someone gets between her and a television camera.

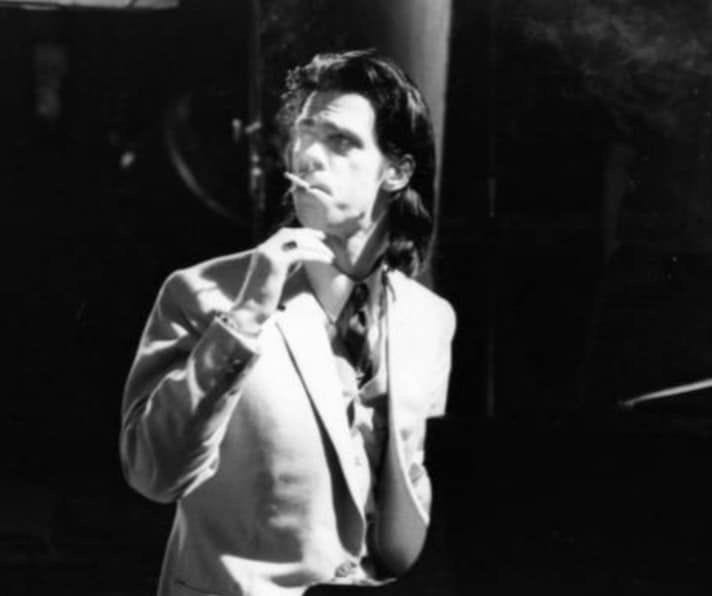

I’d like to say I use my time in the sweat box productively, to commune with my thoughts. But hell with that. I have a hard enough time getting away from those stalkers when I’m not steaming. Instead, I will often listen to books on audio. And one book in particular has captured me lately. Faith, Hope and Carnage, by the Australian rocker Nick Cave, who has done more for black suits than anyone since Johnny Cash, with whom he collaborated in Cash’s twilight. It’s a book that is essentially a protracted conversation with his interlocutor, the Irish writer Sean O’Hagan, conducted mostly during the time-stilling thick of the pandemic, which plenty, including Cave and I, thought might be the shared crisis that finally brought us all together. (Boy, were we wrong.)

Even for those of us who fancy ourselves believers — a label I’ve never shrunk away from in these pages — it is easy to wonder during these constantly chaotic times whether God has taken a powder, or maybe an extended steam. In contravention of the Scriptures I had drilled into my head as a boy, the righteous often seem forsaken. The wicked prosper. The Just Judge seems to be gummed up by procedural delays.

What’s going on? I’d be lying if I said I knew, because I don’t. I’m not God, even if I sometimes do bad impersonations of him in Substack columns. But one thing that bucks me up in my own uncertainty is to watch other believers struggle with theirs’. And Nick Cave, God bless him, is one of those.

Though I’ve played Cave tunes in these pages before, I’ve never been a true aficionado of his music. I take some songs, leave others, and have never been a close student. His music has been described as everything from post-punk to goth rock to “skeletal blues,” none of which really capture all or even most of the incarnations he has perpetually evolved through over the years. Pinning a genre on him feels like a grave disservice. He is his own thing. And I’m happy to let him be. Contain him at your own dorkish rock-crit reductive peril.

And his book is much like his music, all sorts of un-peggable grand themes running through it. His publisher’s dust-jacket copy serves as one of the rare examples in the trade of not being guilty of overstatement. Cave’s is indeed a “profoundly thoughtful exploration” of “belief, art, music, freedom, grief and love.” All words that ring my bells (with the exception maybe of “grief”), and should yours’, too. Though grief, one gets the sense, is the white-hot forge that shapes the metal of his reflection. For the book was hatched shortly after Cave’s 15-year-old-son, Arthur, fell off a cliff in the British seaside town of Brighton, near the Caves’ home. It was an accidental death that an inquest determined came after young Arthur took LSD. After the book’s completion, Cave likewise lost an older adult son to a drug overdose in a seedy Melbourne motor inn. And considering Cave’s father was killed in a car accident when the former was just 19, if you want to read someone whose faith is hard-won, and came in spite of paying lots of loss tolls, Cave’s your man.

As I infrequently do in these pages when I have a burning enthusiasm, I’m going to quote-dump. And I am not going to try to artfully set up excerpts, nor adorn them with pretty writing on my end. I just want you to have something of the same experience I did in the steam box, minus all the sweating. So I’ll give Cave and his buddy O’Hagan the floor, and then some. Real room to work. I just so happen to think Cave, a conflicted Christian himself, is a man worth listening to on the often symbiotic subjects of faith’n’doubt. The second often serving as an integral part of the first, as anyone who has read those great Old Testament books of struggle and rude questions — Job, Habakkuk, Ecclesiastes — well knows. All quotes are in italics, set off by speaker designation between Cave and his interviewer, O’Hagan. Most of the quotes I’m pulling come from two chapters, titled “The Utility of Belief” and “Doubt and Wonder,” which I’m mixing and matching just a little out of order. With ellipses tagged on to the end of comments when there’s a break in the conversation and they pick up elsewhere. Here goes:

O’Hagan: I sense that you are actively attending that yearning now. {A longing for belief in the face of the impossibility of belief.}

Cave: Well, yes, mainly because I’ve gotten older, I have also come to see that maybe the search is the religious experience — the desire to believe and the longing for meaning, the moving towards the ineffable. Maybe that is what is essentially important, despite the absurdity of it. Or, indeed, because of the absurdity of it. When it comes down to it, maybe faith is just a decision like any other. And perhaps God is the search itself.

O’Hagan: But doubt is still part of your belief system, if I can call it that?

Cave: Doubt is an energy, for sure, and perhaps I’ll never be the person who completely surrenders to the idea of God, but increasingly I think maybe I could be, or rather that I was that person all along.

O’Hagan: It’s intrinsically human to doubt, though, don’t you think?

Cave: Yes, I do. And the rigid and self-righteous certainty of some religious people — and some atheists, for that matter — is something I find disagreeable. The hubris of it. The sanctimoniousness. It leaves me cold. The more overtly unshakeable someone’s beliefs are, the more diminished they seem to become, because they have stopped questioning, and the not-questioning can sometimes be accompanied by an attitude of moral superiority. The belligerent dogmatism of the current cultural moment is a case in point. A bit of humility wouldn’t go astray.

O’Hagan: So just to make sure I’ve got this right: you would like to get past your doubt and just believe wholeheartedly in God, but your rational self is telling you otherwise.

Cave: Well, my rational self seems less assured these days, less confident. Things happen in your life, terrible things, great obliterating events, where the need for spiritual consolation can be immense, and your sense of what is rational is less coherent and can suddenly find itself on very shaky ground. We are supposed to put faith in the rational world, yet when the world stops making sense, perhaps your need for some greater meaning can override reason. And, in fact, it can suddenly seem the least interesting, most predictable and least rewarding aspect of yourself. That is my experience, anyway. I think of late I’ve grown increasingly impatient with my own skepticism; it feels obtuse and counter-productive, something that’s simply standing in the way of a better-lived life. I feel it would be good for me to get beyond it. I think I would be happier if I stopped window-shopping and just stepped through the door.

O’Hagan: I’d say, be careful what you wish for; certitude is seldom good for creativity.

Cave: I guess not, but who says creativity is the be all and end all? Who says that our accomplishments are the only true measure of what is important in our lives? Perhaps there are other lives worth living, other ways of being in the world………….

O’Hagan: A lot of people…..have endured a religious upbringing and are now particularly resistant to it — I include myself, to a degree.

Cave (who grew up singing in his Anglican church choir, and who still goes to church, even as he sometimes did during his two-decade-long heroin addiction): Yes, sadly, organized religion can be atheism’s greatest gift……..

O’Hagan: Could you talk a bit more about the tension between doubt and faith that you allude to earlier? I know it’s something you have grappled with for a while.

Cave: There is something about that dynamic that interests me, not least because I have to accept that part of the fire and energy of my life comes from the fact that I devote a significant portion of my time to thinking about and agonizing over something that may well not exist! So, in a way, it may actually be the doubt, the uncertainty and the mystery that animates the whole thing……So for me personally, having a religious dimension in my life is highly beneficial. It makes me happier, it makes my relationships with people more agreeable, and it makes me a better writer — in my opinion…….I think there is more going on than we can see or understand, and we need to find a way to lean into the mystery of things — the impossibility of things — and recognize the evident value in doing that, and summon the courage it requires to not always shrink back into the known mind…….

{On recording his 2019 album, Ghosteen, in the aftermath of his son’s death}:

O’Hagan: …..Do you think you created that music in the presence of something or someone divine?

Cave: That’s a big question, Sean. What I will say is that, from where I’m standing, an explicit rejection of the divine has to be bad for the business of songwriting. Atheism has to be bad for the business of making music. It has to put you at a distinct disadvantage of the fundamentally sacred dimension of music. It’s just very limiting, in my experience. Many people will, of course, disagree, although I tend to think most musicians have more time for these spiritual considerations, because when they make music, when they lose themselves in music, fall deep inside it, they encounter such strong intimations of the divine. Of all things, music can lift us closer to the sacred……..

O’Hagan: And yet there are many great songs and pieces of music that don’t reach into the divine. You’ve written some of them……A song like ‘Breathless,’ for instance, seems to me to exalt the luminous beauty of the everyday. Is that not a wondrous subject in and of itself?

Cave: Yes, and the luminous and shocking beauty of the everyday is something I try to remain alert to, if only as an antidote to the chronic cynicism and disenchantment that seems to surround everything, these days. It tells me that, despite how debased or corrupt we are told humanity is and how degraded the world has become, it just keeps on being beautiful. It can’t help it. But ‘Breathless’ is, in fact, an explicitly religious song. A love song to God…….I mean that all my songs are written from a place of spiritual yearning, because that is the place that I permanently inhabit. To me, personally, this place feels charged, creative and full of potential. …….Ghosteen certainly is a record that feels as if it came from a place beyond me and is expressing something ineffable. I don’t know quite how to explain this, Sean, except that perhaps God is the trauma itself.

O’Hagan: You’re going to have to try to explain that one. What do you mean by ‘God is the trauma itself?’

Cave: That perhaps grief can be seen as a kind of exalted state where the person who is grieving is the closest they will ever be to the fundamental essence of things. Because, in grief, you become deeply acquainted with the idea of human mortality. You go to a very dark place and experience the extremities of your own pain — you are taken to the very limits of suffering. As far as I can see, there is a transformative aspect to this place of suffering. We are essentially altered or remade by it. Now, this process is terrifying, but in time you return to the world with some kind of knowledge that has something to do with our vulnerability as participants in this human drama. Everything seems so fragile and precious and heightened, and the world and the people in it seem so endangered, and yet so beautiful. To me it feels that, in this dark place, the idea of a God feels more present or maybe more essential. It actually feels like grief and God are somehow intertwined. It feels that, in grief, you draw closer to the veil that separates this world from the next. I allow myself to believe such things, because it is good for me to do so……

O’Hagan: ……Just to stay with the ‘what if’ question, does it not in itself leave room for doubt as well as wonder?

Cave: Yes, doubt and wonder. Well put.

O’Hagan: That’s quite a dynamic, though — almost contradictory.

Cave: Well, I think the only way I can fully give myself over to the idea of God is to have the room to question. To me, the great gift of God is that He provides us with the space to doubt. For me at least, doubt becomes the energy of belief.

O’Hagan: That’s fair enough, I guess, but it’s starting from the premise that God exists and allows us to doubt, which an atheist would argue is essentially flawed logic. What would you say to that?

Cave: Well, Sean, since when has belief in God had anything to do with logic? For me, personally, it is the unreasonableness of the notion, its counterfactual aspect that makes the experience of belief compelling. I find that leaning into these intimations of the divine, that for me do exist, as subtle, softly spoken and momentary as they may be, expands my relationship with the world — especially creatively. Why would I deny myself something that is clearly beneficial because it doesn’t make sense? That in itself would be illogical………

O’Hagan: Do you think this precarious moment we are living through could be collectively transformative in any lasting way?

Cave: Yes. I remain cautiously optimistic. I think if we can move beyond the anxiety and dread and despair, there is a promise of something shifting not just culturally, but spiritually, too. I feel that potential in the air, or maybe a sort of subterranean undertow of concern and connectivity, a radical and collective move towards a more empathetic and enhanced existence. I may be completely off the mark here, but it does seem possible — even against the criminal incompetence of our governments, the planet’s ailing health, the divisiveness that exists everywhere, the shocking lack of mercy and forgiveness, where so many people seem to harbor such an irreparable animosity towards the world and each other — even still, I have hope. Collective grief can bring extraordinary change, a kind of conversion of the spirit, and with it a great opportunity. We can seize this opportunity, or we can squander it and let it pass us by. I hope it is the former. I feel there is a readiness for that, despite what we are led to believe. I have a hope that, in time, we can come together, even though, right now, we could not be further apart.

Bonus Tracks: While this sounds nothing like the angry-young-man version of Nick Cave back in his post-punk days fronting The Birthday Party in the early eighties, this song slays me. It’s called “Lavender Fields,” off his 2021 album Carnage, recorded with his frequent collaborator and member of The Bad Seeds (Cave’s band), the multi-instrumentalist wizard, Warren Ellis. The song came to Cave as a result of his conversations with Sean O’Hagan (excerpted above), which he has said “fell out of the sky, almost complete, like a gift,” as he was sitting on his sofa, where he never writes. (“I watch TV on my sofa.”) Makes sense that it came from another world, because it sounds like it, as well.

This clip is from the compelling 2016 Andrew Dominik-directed documentary, One More Time With Feeling, which documented Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds making their sixteenth studio album, and happened to coincide with the death of Cave’s son, Arthur. The album’s title song, “Skeleton Tree,” was the only one written after his son had perished.

And because it’s one of my favorite Pogues’ songs, here’s Cave performing “A Rainy Night In Soho” at the funeral of his longtime friend and Pogues’ lead singer, Shane MacGowan, back in December. I played MacGowan’s version here two months ago, but Cave’s cover makes it worth a repeat:

Terrific column - thank you. There are few - and maybe no - parts of our lives where having some humility is a bad idea. The entire premise of faith is having the humility to believe in something that you cannot see. Even the irreligious could benefit from some humility: if you look at what science or medicine were 100% certain of 100 years ago that is now incontrovertibly wrong, you can pretty easily see where they could benefit from some humility, too.

Mr. Cave has gone through some awful tragedies and is searching for Answers. I applaud the wide net he is casting as he searches.

"I sweat harder than Nancy Mace when someone gets between her and a television camera."

Great line. Thank you, as always, Matt.