The Man You Should Be Reading

How a dead Trappist monk keeps dropping truth bombs on us today

Swimming in the news stream all day – as too many of us tend to do – can be a bit like swimming in the East River. If you form your body into a buoyantly-shaped object, the water can keep you afloat. But don’t be surprised when you emerge from it slicked with industrial runoff, human waste, and cadaver juice. It’s not that the news today is any worse than it ever was. War, pestilence, greed, dishonesty, cruelty – these are not new stories. There’s just more messengers delivering the bad news with ruthless efficiency than ever before.

Sometimes, the only remedy is a scalding shower for the insides. And when I need one, I often turn to a dead Trappist monk, which is weird, because I’m not even Catholic. The Baptist minders of my youth wouldn’t hear of me regarding a papist as a spiritual lodestar, elsewise, I might get fancy ideas about worshiping Mary or about the broken Saltines in the communion tray turning into Jesus’s actual flesh. “Cannibalism is un-Christian,” I can almost hear them tutting. And wine turning into J.C.’s blood was a non-starter too. Not so much on anti-vampirism grounds. But on anti-wine grounds. All good Baptists of my upbringing knew that Jesus’s blood should be represented by Welch’s grape juice. Upgrade it to a nice Syrah, and you’re not only promoting drunkenness, but really cutting into the tithes and offerings.

But this offering isn’t about my Baptist flashbacks. It’s about a man whose words throw me a lifeline with great regularity.

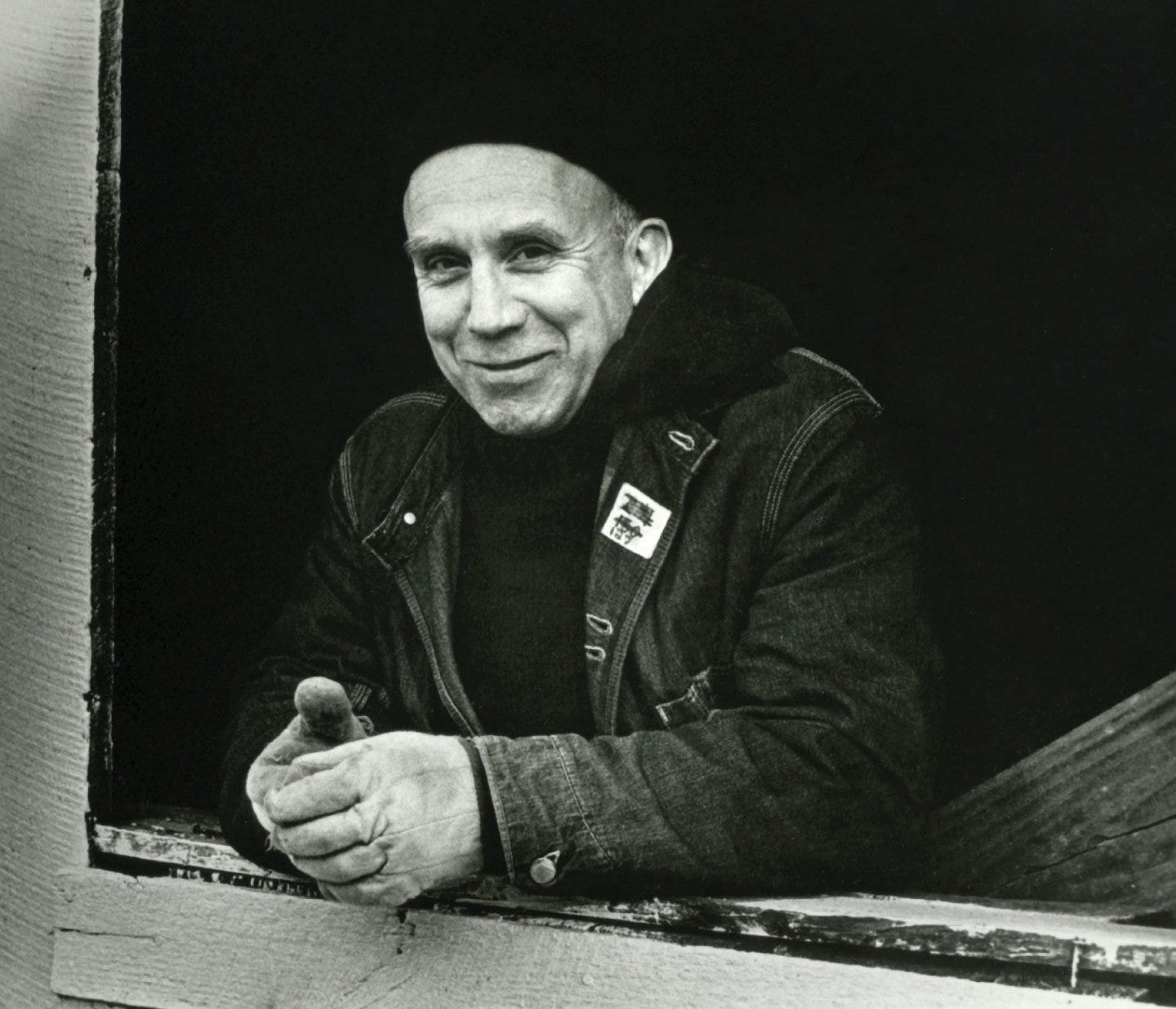

I’ll spare you most of the details of Thomas Merton’s fascinating biography – that’s why God invented Wikipedia. But the SparkNotes version is that he was born in France in 1915 to a New Zealand painter (his father) and an American Quaker/artist (his mother), who’d met at a Paris art school. Neither of his parents stuck around terribly long. Merton’s mom died of stomach cancer when he was six years old, and his father of a brain tumor when he was 15, firing Merton’s spiritual search since so much in his life had gone missing.

Precocious, social, forever intellectually-curious - Merton was educated first at Cambridge, and then at Columbia University in Manhattan, where he minored in boozing, womanizing, and going to jazz clubs. Right around this time, as Merton was becoming acutely conscious of his own emptiness, God caught his attention and never lost it. Once harboring pretensions of being a literary grandee, Merton instead became a made member of Our Lady of Gethsemani, a Trappist monastery near Bardstown, Kentucky, where he lived cloistered for the rest of his relatively short days. (At one point, he was only allowed to receive letters four times per year.) Merton expired in 1968 at the age of 53. He was found dead in his room at a Red Cross retreat center near Bangkok - where he was lecturing at a monastic conference - with a short-circuited Hitachi floor fan strewn across his body which some think he grabbed for after stepping out of the shower.

Along the way, Merton made his bones as a monk and a mystic, as a teacher, a theologian, a social commentator (he was aggressively antiwar), and even as an appreciator, if not an adherent, of eastern spiritual traditions. This had plenty of his own suggesting he was a heretic, while the likes of the Dalai Lama and Thich Nhat Hanh regarded him as a friend and a true-blue exemplar of Christianity. Merton’s literary ambitions were also realized. He became a publishing sensation after his abbot prodded him to write his life story. The Seven Storey Mountain was published in 1948 – a book Merton himself later held in low regard for being too immature and rigid. Then he never looked back. If you’re a Merton completist – and I’m not – you could be at it for a long time. Merton wrote over 50 books in 27 years, and that doesn’t account for all his essays, poems, letters, and voluminous journals. It turns out, living like a monk can be good for word-slinging output. (I’ve had impatient editors who wished I’d have become one, too.)

While I often dip into individual titles of Merton’s, my dipping-instrument-of-choice has become a little-circulated book, published in the early ‘80s, called Through the Year with Thomas Merton: Daily Meditations from His Writings, selected and edited by Thomas P. McDonnell. The literary equivalent of a greatest hits album, Through the Year doles out choice passages over a calendar year (they’re so good, that I tend to gobble down many days at once, even in re-reading) that pull from many of Merton’s works such as The Sign of Jonas, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, and New Seeds of Contemplation. When I love a book, I tend to love it to death – and of Through the Year’s 226 pages, roughly four-fifths of them contain my dog-ears and/or underlines. (Henceforth, I will use italics instead of quotation marks to set off Merton’s writing, except when I don’t.)

Merton both gloried in nature and jealously guarded his solitude – without which, he held, you couldn’t hear the voice of God or even your own. He did so to the point that he carved out a hermitage even within the monastery, living many years alone in a shack on the grounds. And yet, as McDonnell writes, he still had ample gifts for society, a ready wit, and relished conversation with visitors to the Abbey of Gethsemani, “especially when they were thoughtful enough to have brought beer along with them.” As Merton’s renown grew, everyone from Joan Baez to Wendell Berry sought out his company.

Yet for a guy who didn’t watch television, Merton seemed to be exhausted by the omnipresence of the world pressing in even as he labored to make sense of the tumult of his times: We are like a bunch of drunken men at the last end of a long stupid party, falling over the furniture in the twilight of dawn…..Hell is where no one has anything in common with anybody else except the fact that they all hate one another and cannot get away from one another and from themselves. Or were those our present times he was anticipating? It can be hard to tell.

People are eating their hearts out with fury and self-hate, just when they have all the money and all the leisure and all the opportunity, apparently, to really live. They find that the kind of life everyone dreams of is in fact impossible. They cannot face leisure. They cannot handle prosperity. I think we would be happier in a real crisis, instead of in a constant series of imaginary ones that we cannot possibly live with. Perhaps this unconscious sense of unreality will finally drive us all into a real cataclysm, just to have the relief of getting away from fictions and imaginations!

And so, Merton, while keeping an engaged hand in the world, taking hard stands against everything from war-mongering (during early Vietnam days) to racial injustice, also understood the necessity for self-preservation by holding it at arm’s length in passages that seem to presage, say, Twitter: Do everything you can to avoid the noise and the business of men. Keep as far away as you can from the places where they gather to cheat and insult one another, to exploit one another, to laugh at one another, or to mock one another with their false gestures of friendship…...Those who love their own noise are impatient of everything else.

Merton’s paradox was that he took frequent breaks from humanity to see it more clearly, as well as to not resent it: It is in deep solitude that I find the gentleness with which I can truly love my brothers. The more solitary I am, the more affection I have for them. It is pure affection, and filled with reverence for the solitude of others. Solitude and silence teach me to love my brothers for what they are, not for what they say. Because what they say is often untrue. From our politics to our punditry, he had our number:

How is it that our comfortable society has lost its sense of the value of truthfulness? Life has become so easy that we think we can get along without telling the truth. A liar no longer needs to feel that his lies may involve him in starvation. If living were a little more precarious, and if a person who could not be trusted found it more difficult to get along with other men, we would not deceive ourselves and one another so carelessly. But the whole world has learned to deride veracity or to ignore it. Half the civilized world makes a living by telling lies. Advertising, propaganda, and all other forms of publicity that have taken the place of truth have taught men to take it for granted that they can tell other people whatever they like, provided that it sounds plausible and evokes some kind of shallow emotional response.

Yet Merton’s truth flame-thrower wasn’t just directed outward. He took it to himself, as well, since self-deception often serves as the headwaters from which the lies we tell others flow downstream. The monsters we loathe in others, and are often able to see more clearly, are sometimes just as present in our mirrors as on our screens:

We must be wary of ourselves when the worst that is in man becomes objectified in society, approved, acclaimed and deified, when hatred becomes patriotism and murder a holy duty, when spying and delation are called love of truth and the stool pigeon is a public benefactor, when the gnawing and prurient resentments of frustrated bureaucrats become the conscience of the people and the gangster is enthroned in power, then we must fear the voice of our own heart, even when it denounces them. For are we all not tainted with the same poison?

This, perhaps, is why the monk who couldn’t stop writing had to wrestle with himself about the importance of leavening his prodigious output with silence. Not that words don’t matter. Merton understood that for both good and ill, they shape the world we live in. Which is why we should strive to make them count: If our life is poured out in useless words, we will never hear anything, will never become anything; and, in the end, because we have said everything before we had anything to say, we shall be left speechless at the moment of our greatest decision.

We return to Merton – or at least I do, over and over again – because even if he doesn’t solve the world’s problems, he at least gets under the problem skin, and correctly diagnoses what’s causing it. Too often, it is a lack of wisdom and humility. They tend to be tag-team partners. And neither are evidenced much in our public square, or even in our private spheres. This is perhaps why Merton himself prayed: Teach me to bear a humility which shows me, without ceasing, that I am a liar and a fraud and that, even though this is so, I have an obligation to strive after truth, to be as true as I can, even though I will inevitably find all my truth half poisoned with deceit.

For despite his turns as an angry prophet, he also knew that as a man who spent his whole life serving Christ, “Christ is found not in loud and pompous declarations, but in humble and fraternal dialogue. ” He knew that “in humility is the greatest freedom” since “as long as you have to defend the imaginary self that you think is important, you lose your peace of heart. As soon as you compare that shadow with the shadows of other people, you lose all joy, because you have begun to trade in unrealities, and there is no joy in things that do not exist.” Merton told himself the hard truths he told others, such as:

As soon as you begin to take yourself seriously and imagine that your virtues are important because they are yours, you become the prisoner of your own vanity, and even your best works will blind and deceive you. Then, in order to defend yourself, you will begin to see sins and faults everywhere in the actions of other men. And the more unreasonable importance you attach to yourself and to your works, the more you will tend to build up your own idea of yourself by condemning other people. Sometimes virtuous men are also bitter and unhappy, because they have unconsciously come to believe that all their happiness depends on their being more virtuous than others…….The greatest need of our time is to clean out the enormous mass of mental and emotional rubbish that clutters our minds and makes of all political and social life a mass illness. Without this housecleaning we cannot begin to see. Unless we see, we cannot think.

And so, even an old Baptist like me is left with little choice but to love and treasure Merton. For more than just about any other writer in my library, he saw clearly. And what he saw most clearly of all is that we’re badly in need of turning the lights on: We are supposed to be the light of the world. We are supposed to be a light to ourselves and to others. That may well be what accounts for the fact that the world is in darkness!

Bonus track: Though Merton loved music, I don’t have a Merton-themed musical tie-in today. But sticking with the seeing-clearly motif, this seems as good an opportunity as any to spring one of my favorites on you: Susan Tedeschi and her guitar-hero husband, Derek Trucks, along with Warren Haynes, singing Etta James’s “I’d Rather Go Blind” at the White House. Love Obama or hate him (I was never a fan), but at least he has good taste in music. Pay special attention around the 2:40 mark, where Trucks makes his slide guitar sing like heavenly hosts.

Everyone has there personal strategy for coping with the issues identified in this wonderful piece. Many of these comments communicate some successful approaches. For me, I simply manage my information/communication diet very closely. I do not use twitter, facebook, etc. as I find more noise than signal in those channels. I also severely limit my intake of "opinion" outlets to those that do not appear to be rage pornographers. I rarely post comments, on-line, as most of these "communities" serve as outlets for the embittered and illogical. I see very little value added. I spend almost no time in the "virtual" world. I share this information in the spirit of one who has learned from each of you and Matt. I also want to assert that it is possible to find happiness, as some others of you have. Maybe, one of you might find something of value in what I have posted. Or not. I could be the biblical banging gong. I am happy either way.

Yes Matt, love, mercy and grace. God extends to us these precious gifts if we will only humble ourselves. In turn we are to extend to others these same gifts. Others may not deserve them but neither do I.