I’ve never claimed to be the brightest bulb on the tree. I graduated from a mediocre state school where I lived up to its mediocre standards, studying journalism and film, if “studying” isn’t too strong a word for padding your GPA by intermittently showing up to class to jaw with wizened professors and nose-pierced coeds in Doc Martens about whether Citizen Kane’s “Rosebud” symbolized a clitoris, or just a sled. My parents paid actual money for this.

But I was reminded of my own iffy candlepower the other night when checking on the Christmas tree. We’d bought it a couple days after Thanksgiving. And while I was in favor of letting the branches settle after they’d been bound on the tree-truck, my wife couldn’t wait. After all, according to the Hallmark Channel/retail industrial complex, Christmas season was already three or four months old. Time was a’wasting.

Alana immediately strung it with lights and decorated it with tasteful ornaments, not with the garish homemade jobs we used to feel obligated to showcase when the kids were young, featuring their paintings of Blitzen taking a Christmas dump before his all-night ride, or a Popsicle-stick likeness of Judas Iscariot, who’d go on to distinguish himself as the babe-in-the-manger’s least favorite disciple. (My kids liked antiheroes.) We impaled the tree’s trunk by tightening the stand screws into it, a tree crucifixion — Christmas has almost as much symbolism as Citizen Kane — and I filled the stand with water. But just ten hours later, I hit the deck and slid under the tree to dip my fingers into the stand, double-checking the water level. The tree had slurped it up and drunk it dry, like Shane MacGowan at a Tipperary happy hour. (Though every hour was MacGowan’s happy hour. RIP, old friend.)

My dry fingers caused me to exclaim to nobody in particular, “Holy hell, this thing is still alive!” (As mentioned, I majored in journalism, not forestry.) Of course, I knew it was alive, but it was fun to be surprised by this in such immediate fashion. Since it being alive is the whole reason I still buy real trees, and have not gone over to the dark side like the 80 percent or so of the citizenry who the American Christmas Tree Association says now settle for artificial. The latter are tidier, less expensive over time, and tend to have a perfect shape, if you’re into that sort of thing. Still, I’m about as interested in artificial trees as I am in artificial intelligence or artificial breasts. When I see, smell, taste, and touch things, I like them to possess their original character. (No offense to readers with breast augmentation — after all, the outside is still real, and I’m forbidden from touching them, in any case.)

I still treasure the ceremony of tree procurement, though it’s changed over time. Once, when we lived in Germany, my military father marched us off to the woods of the small farm village we lived in to chop down a perfect looking specimen in the wild. He didn’t have a chainsaw, and his hacksaw was dull, so I think it only took about three hours. We could’ve probably gnawed it down faster. But most years, when we lived in Texas, we’d leave in early morning to comb the Christmas tree lots — my dad was a Christmas-tree perfectionist — and wouldn’t get back until after dark. By then, I’d be so exhausted, I seriously considered converting to Judaism. But I was riding shotgun with my pop, and he was serious about it, so I tried to be, too.

He’d inevitably buy a bushy Scots pine, which I prefer, but can no longer find these days. Most tree lots now only feature firs of the Fraser or Douglas variety — with their prim needles and clean-cut profiles, perhaps an effort to ape their artificial brethren. The Scots pine is to Christmas trees what Sam Bankman-Fried is to hairstyles: wild and untamed. It being San Antonio, we never saw snow. But that didn’t stop us from getting our tree flocked with fake snow, trying to deceive the neighbors that our 75-degree living room had been transformed into a winter wonderland. God only knows what that stuff was made of. Google tells me that in the old days, fake snow was manufactured by using every substance from borax to ammonia to asbestos. Whatever our poison, my sister and I will treasure the memory of the light dusting on our Christmas presents when we’re old and bedridden with mesothelioma.

We don’t flock our trees anymore. And unlike my dad, I can find the perfect real tree, or perfect enough, by going to the Optimist Club lot in front of the Safeway, getting in-and-out in 20 minutes or less. It feels kind of like rescuing a dog for a month, only to take it to slaughter in January. Still, I enjoy the rituals: Digging through the closet for my kayak tie-down straps that we use to tether the tree to the roof of the car, praying it doesn’t fly off and through someone’s windshield in a yuletide massacre. Enduring the barbs of my now-grown kids who mock me yet again for measuring how much room we have from the stand to the ceiling, in order to leave enough room for the treetop star. (“The ceiling hasn’t grown, Dad,” says Bastard One. “It’s the same height as it was last year,” says Bastard Two. My threat that nobody, not even Santa, likes a smartass, no longer instills fear.) Alana popping in the go-to Christmas CD, Vincent Guaraldi’s soundtrack to A Charlie Brown Christmas, which my father calls “suicide music,” but which I like. It puts a little blue into Blue Christmas, which can sometimes get too cheery for its own good.

I like the scent of pine resin getting on hands and clothes, making me smell like a Yankee candle. Back when I still bought my tree at a local farm stand, before Farmer Joe got shut out of the business due to a Christmas tree shortage after the last economic downturn, he used to save me a box of the pine heels they’d saw off so the trees could take a clean drink of water when you got them home. They make ideal kindling in your fireplace, assuming you don’t have a gas one. If you do, I’m so sorry. You really are missing out. Winter isn’t winter without woodsmoke.

But it’s not just Christmas trees that bring me pleasure. It’s all trees, really. If you’re lucky, you’re surrounded by them. And if you’re not surrounded by them, you should make your own luck, and go to places where you can be. I spend a lot of time walking through woods. Usually with the dog, who is an ideal companion, since he doesn’t contaminate our sanctuary with idle chitchat.

I’m not some weirdo dendrophile paraphiliac or anything. (People who get wood from being around trees.) Neither am I an expert arborist. My Peterson Field Guide sits on the shelf, mostly unused. I know some basics. I can recognize the softwoods from the hardwoods, the deciduous from the evergreens, the difference between a spruce and a fir. But I mostly don’t worry about tree identification. That’s why God — or our new gods in Silicon Valley — invented apps like LeafSnap. It’d be cool to be able to identify all my forest friends at a glance. But the beauty of being among them is that there’s nobody there to dazzle with such knowledge. The dog doesn’t care. He just likes to sniff and pee on them. And the trees don’t either. Which is why I so often prefer their company. I don’t have to impress them, even if they spend their lives impressing me.

One of my favorites stands next to a dirt path in a geese refuge off my home river. When I ride my bike up from the pier, surveying our Canadian buddies pitching camp for the winter, there stands a magnificent colossus, a southern red oak that the rangers tell me could be cracking 200 years old. Sometimes, at this late date, its branches just seem to break off, like hair relinquishing its grip on an elderly scalp. And yet, after the keepers remove those, it still looks as awe-inspiring as ever, its spread going on for days. Its trunk is so large, that every time I bike up the rise where it appears, I dismount, and hug it. Yes, I am indeed a literal tree-hugger. (A platonic one.) The other day, I measured it off by spreading my arms as far as they’d go, and had to move around it six times to cover its circumference.

I also say a prayer. Not to it, but for it. A prayer of gratitude for laying eyes on something that has seen so much more life than I have. A prayer of saditude, I guess we’ll call it, since my prayer is tinged with sadness that this tree can’t keep standing forever. When it was born along this river I treasure, the internet didn’t exist. Neither did aviation or automobiles. It might’ve very well seen the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla harassing the Brits during the War of 1812, on the latter’s way to burn the Capitol down. We seem hellbent on doing that to ourselves nowadays. I sometimes wonder what the oak would say to that if it could talk. But luckily, it can’t. Unlike the rest of us, forever expressing, trees hold their secrets close.

If you can only buy one Christmas gift for someone this year, and they already have enough merino wool sweaters or dry wick workout wear from the Yuppie Store, you ought to buy them a Slack Tide subscription, of course, to rescue them from their impoverished lives.

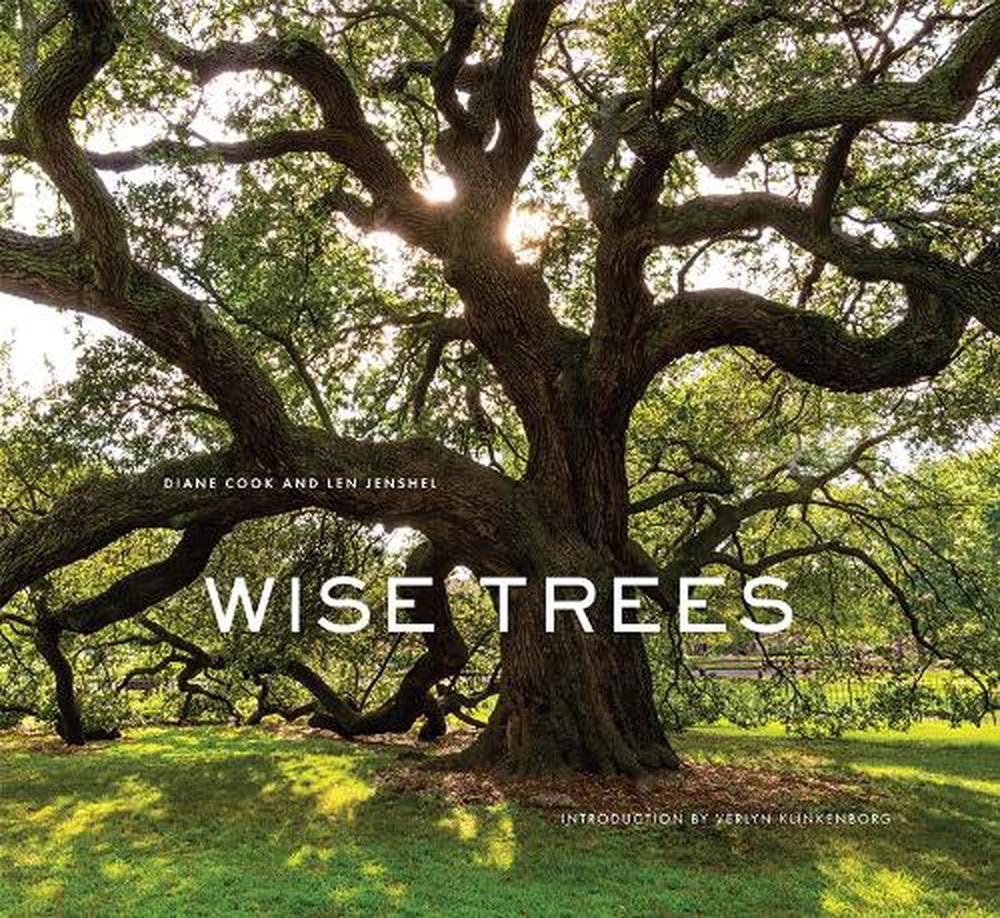

But if you have two gifts to give, you might also consider a photo book I happened on a few years back, Wise Trees. I like everything about it, even its epigraph from William Blake: “A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees.” It features all manner of wonders, with accompanying capsule write-ups: from the gnarled 2,000-year-old Sacred Camphor of Atami, Japan, where Shinto followers believe the kami of the tree — or a hidden spirit that can inhabit natural elements — will extend a person’s life by one year for every lap around its gargantuan trunk that one completes; to Te Aroha (or “The Love”) of Cape Reinga in New Zealand, a pohutukawa tree that is relentlessly battered by wind and sea spray, but which has held on to the edge of a rock for 800 years, in a place the Maori believe is “the leaping-off place of spirits.” From which the spirits travel down the roots of the sacred tree and return to Hawaiki, the land of their ancestors.

In his fine introduction, Verlyn Klinkenborg writes:

Humans have always been framed by trees, from the original savanna onward. As Emerson put it, ‘They nod to me, and I to them.’ So imagine inhabiting a world where the largest trees are only shoulder high and live just a single human generation: twenty to twenty-five years, considerably shorter than the average human lifespan. Suppose too that they decompose after death as swiftly as we do. Picture yourself walking among the forests of that strange arboreal world, gazing across the treetops like a giraffe in an apple orchard. How would it feel? How would it change your conception of who you are? In our world, we’re dwarfed, outlasted, and even humbled by trees. What little modesty we have as a species may depend partly on that fact.

Some of the trees I have the deepest reservoir of affection for are ones that no longer exist. Our house sits on a hill, and we have a pretty good view from the porch, looking down on the neighborhood, especially the canopy of trees that lines our street. But our own magnolia and a dwarf peach both grew out-of-control enough that they completely obstructed our view. My wife insisted we cut them down, to restore the vista. I wanted it back too, and she was right, as is often the case. But I consider it something of a sin to cut down perfectly good trees, unless someone’s giving me theirs so I can split and burn firewood — two additional gifts that trees give us.

The dwarf peach looked more like an electrocuted shrub. It wasn’t pretty. Its tiny fruit was bitter. Not fit for cobbler, let alone, eating raw. And yet, it’s the tree my kids and I used to stand around when we were both a lot younger, and got bored with tee-ball practice. Instead, we’d take the baseball bat, pick those bitter little peaches off the ground, and peg them into the woods, the satisfying splat giving way to peach juice running down the bat grip onto our hands, which the dog seemed to enjoy with the licking sessions that ensued. If it’s a sin to cut down any live tree, it is a mortal sin to cut down a magnolia. But it, too, was an ugly unruly version of one. An overgrown bush, more than a proper tree. Even if my yellow lab, Levi, used to shade himself under its branches. And his successor Moses, a rescue Bernese Mountain dog who took a while to learn his manners, once treed one of my sons up it after ripping off his shirt. When the executioners came to cut it down, and gave me what was left of the wood, I put it next to my woodpile, but couldn’t bring myself to split or burn it. It felt too much like doing violence to my own life.

I have such a soft spot for trees, I find it hard to fell even dead ones. A few years back, a huge white pine that sat smack on the border of my neighbor’s and my yard died right in front of our eyes. It was the favored perch of my bluebirds, who used to man their watchtower trying to spy crickets and grubs in the yard to assassinate. Its needles turned brown, and became as dry as straw. Its overgrown limbs — many themselves as thick as standalone trees — started collapsing under their own weight. My neighbor came over and cautioned me: “We’ve got to take that thing down, or it’s gonna come down on one of our roofs.” I knew he was right. So I gave in reluctantly. But when the hitmen came, cutting my old friend up into small pieces, giving me the rounds, then offering to take out the stump, I told them to leave it. And not just because I’m cheap, and didn’t feel like forking over the extra 500 bucks. I needed something to remember that tree by, even if I’d spend the rest of my days smacking my lawnmower deck into what was left of it.

But the hardest tree I’ve had to say goodbye to — which has also been the longest goodbye — is to the weeping willow on my in-laws’ land. It has a lot of memories for me. It was the tree that overlooks the clearing next to a creek where we got married. It’s the tree where I used to tie up the late Levi, who was too rambunctious to sit in a kayak with us when we made our way out to the river. We had to leave him behind after first trying to exhaust him by making him swim for fetching sticks before we departed. No matter. We could hear his barks of displeasure all the way down the creek.

It’s a tree that holds even more memories for my in-laws, because it is the tree they planted after their daughter, my wife’s little sister, died in a car accident. She was hit while riding her bike not a mile away from home, two weeks shy of turning ten-years-old. It happened years before I came on the scene. But I’m told that my father-in-law, Vic, a man not given to overt displays of emotion, didn’t cry. He merely spent hours walking in silence in the woods behind his house, his hands in his pockets. Waiting for…….I don’t know what. I’ve never managed to ask him. But I’m guessing he was waiting for his world to come back together, after it had been blown to pieces.

By tree standards, weeping willows don’t last long. They grow fast, but die young. The average lifespan is about 30-50 years, give or take. I thought this one would likely last much longer, since it took root right along a creek, enjoying an endless supply of the water of life. Which turns out, might’ve been the water of death. An arborist told me since the creek water there is slightly brackish, the tree might’ve been drinking slow poison, taking salt into its system.

We noticed the willow started falling apart. At first gradually, then swiftly. Initially, its bark began flaking off. Then you could walk up to it, and literally grab a hunk of wood out of its trunk, like you were tearing off the edge of a sponge. Vic used to run his own construction company, and still had a few big machines at his disposal. One day, without telling anyone he was going to do so — perhaps no longer willing to watch the tree’s accelerating death — he took his front-end loader to it, knocked it down, and pushed it off into the marsh.

It seemed an abrupt move, but maybe a necessary one. We thought that was the end of the tree. And then a strange thing happened. And has kept happening since. Its top, poking out over the marsh, is still sprouting. Every spring, its leaves come back, and it blooms more brilliantly than before. I don’t know how or why. The undergrowth it sits in is so thick, I can’t make out if it’s still rooted, or what’s going on. I suppose with enough determined shoveling, and marsh-plant clearing, I could figure it out. And yet, I don’t want to. The way you’re never quite sure about looking behind the curtain whenever a minor miracle decides to present itself. I don’t want the magician to show me his trick. I just want to believe in magic.

And magic is indeed what it feels like, when I see that once-majestic weeping willow refusing to go down for the count. Sometimes, when I pull my kayak out of the water there, and am rolling it back to the garage, I stop in front of that willow, and drop my boat. I pay my respects to the not-quite-fallen tree, taking in its glorious buds. I have even asked God, “How did this happen? What does it mean?” He hasn’t told me yet. Or if he tried to, I can’t hear him. Maybe the voices in my head trying to assign it meaning are too loud. Sometimes, in my experience, God doesn’t shout, he whispers. Gives you a gentle nudge. And says to you, if you can manage to hear it: “Here’s something beautiful and unexpected. Just take it in. And give your tiny brain that strives to make sense of it all the day off.”

And so whether God is saying that to me or not, that’s what I do. I take it in. Something beautiful, raising its head while lying on its death bed. But it’s not dead yet. It saddens me that it can’t live forever. But what can? And so, I take stock in the saditude, that this magnificent fallen tree has graced me with its beauty as long as it has. Long after I had any reason to expect it to.

Bonus Tracks: As I hinted above, the great songwriter, Shane MacGowan of The Pogues, died two weeks ago, at the age of 65. As anyone who has studied him and his drinking habits — MacGowan has basically been drunk since the early seventies, perhaps even the mid-sixties when he was a pre-adolescent — the question is: what took him so long? He’s looked to be at death’s door for a good 30 years or so, as was evident in the 2020 documentary on him, Crock of Gold. The obvious lesson here for the kids: drink more water. And the obvious move here would be for me to link to his wonderful Christmas duet with the also-late Kirsty MacColl, Fairytale of New York. As nearly everyone has in the retrospectives. But I’ve featured it before in these pages. So I’ll only hyperlink to it now. Though MacGowan once called the tune “our Bohemian Rhapsody,” he claims to have hated it. But I suspect that was just for show, since it’s truly great, and he had to know it.

The song I will feature, however, is one of my favorite Pogues songs, A Rainy Night in Soho. Elvis Costello produced it, and the story goes that he and MacGowan had a terrible dust-up over whether it should feature an oboe (Costello’s preference) or a cornet (MacGowan’s). It being MacGowan’s band, he won the argument. (And though I greatly respect Costello, Shane was correct, in my opinion.) As MacGowan described the row in Crock of Gold: “I blew my top. I kicked him out, I told him to get his fat arse out of the studio and never come back.”

And while we’re at it, what the hell? Let’s throw this cover of Fairytale of New York in from my favorite Christmas special of all-time, the 2015 A Very Murray Christmas, featuring Bill Murray, Paul Shaffer, Jenny Lewis, David Johansen, and a host of others.

"my sister and I will treasure the memory of the light dusting on our Christmas presents when we’re old and bedridden with mesothelioma."

and

"Vincent Guaraldi’s soundtrack to A Charlie Brown Christmas, which my father calls 'suicide music.'"

Literally laughed out loud. But then you tricked us, veering into tree territory without fair warning (to go grab a handful of Kleenexes for the next part).

Because I have to confess to weeping through the rest of it, being a hopeless tree-lover myself. (I've spent the last two beautiful sunny days walking around outside taking pictures of all the trees dressed up in their finest orange, red, and yellow party-wear, an explosion of color we haven't seen in Dallas in years.)

I fully understand the emotional pain of cutting down a live tree (on par with putting a dog down), because I'm a Good Samaritan of trees. My wife and I have planted hundreds and have saved trees that were condemned for the bulldozer. When we were renovating our first house together, and were foresting our lot with magnolias and Nelly R Stevens hollies, our landscaper let us know that there were three large live oaks near the local hospital that were going to be cut down to expand its parking lot. (!) We could have them for free if we paid to have them removed. So we hired a tree specialist with a giant flatbed truck and a crane to have them moved to our yard.

The live oak we planted in front was the one in which we hung a swing, and I pushed both my boys as babies for hours in it (and they would scream for more when I tried to stop). Moving, it was harder for me to leave that tree than it was our house.

We had a giant weeping willow at the house I grew up in Rockford, IL, literally, the largest I've ever seen (at least a six-foot diameter), and my dad let us build a fort in it. Nothing better than sitting in a tree. I fell out of it once, probably a 12-foot drop, and landed on my back. It was the first time I had ever had the wind knocked out me, and I didn't understand what was happening. I thought I was dying and it was terrifying, but I was somewhat comforted by the fact I was lying next to my favorite tree.

(The old pecan outside my window says 'hi.')

Thanks for your courteous response.