Our Lying Problem

And how George Orwell can stop it

Editor’s Note: Have a question about how to erase history if you don’t like how it unfolded? Ask hostage-in-chief Kevin McCarthy and his herd of feral cats who are literally trying to expunge the record, pretending as though their Orange Odin wasn’t impeached twice. Note to future MAGA historians: he was! Bookmark this so you don’t get confused when some mouth-breathing Hillsdale professor tells you, “Well, actually, the Congressional Record, as revised by MTG and Elise Stefanik, indicates that Trump wasn’t impeached…..” For questions concerning the reality-based world, ask Matt at askmattlabash@gmail.com

Dear Matt,

Why is everybody in public life lying so much these days, and how can they be stopped?

Kind regards,

Elisabeth G.

Well, I’d be lying if I said I always tell the truth. According to one college study (college studies/social science being a bastion of habitual lying), even the most honest among us tell up to two lies per day. I myself might tell little white ones here or there – on account of the truth hurting and me not wanting to cause any more pain in this world. Which is not to disparage white people, who are most of my readers. (Where are you, minority subscribers? Be the change you want to see.) Though I like to think my little white lies have an emotional truth to them. “Dramatic legerdemain,” we in the polysyllabic, word-magician business like to call it. Writers, being self-deceivers by nature (how else could they live with themselves?), like to convince themselves they’re lying to you for your own good. Or maybe because they have a deadline, and need to crank something/anything out. Desperation is a jealous mistress.

But truth is a stubborn bugger, and has a way of revealing itself no matter how many confidence men try to suppress it or shell-game it around the table for their own diabolical advantage. I’m no fashion expert, even if I like to look elegantly turned out when accepting prestigious literary awards. But for my most important fashion cues, I turn not to Alan Flusser, but to the apostle Paul, who when writing his letter to the Ephesians while kitting his ideal church up in what he called “The Armor of God,” stipulated that one should gird oneself with the “belt of truth buckled around your waist, with the breastplate of righteousness in place.” Belts of truth? Breastplates of righteousness? Remind you of anyone you know in public life? Probably not. Elise Stefanik sure as hell isn’t wearing those. They’d clash with her shoes/purse, made from the supple hides of gutted fact-checkers.

Which is why I don’t take my truth antidotes from public self-servants. I take them from one of the rare men whose words I steadily trust.

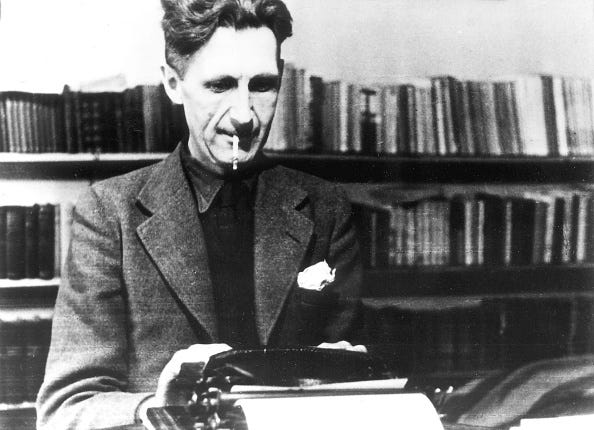

That would be Eric Arthur Blair, better known as George Orwell, even if he’s been dead for 73 years. Is it a writerly cliché to love Orwell? If so, who cares? Clichés become clichés because they have usually arrived at some sort of widely recognized truth: “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.” I still have no actual idea what that means. Eat too much pasta alla gricia? Take long naps? But it sounds true, which is good enough for me. (“Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good” – another cliché truth bomb.)

This is why, a few years ago, I settled on a new Bible – even if I’m still perfectly fine with the old one. It’s something the Gideons should place in motel rooms if they ever run out of King Jameses: a slim volume called Orwell On Truth, which contains, all in one place, the very best pulls from Orwell’s prodigious output. He committed a considerable amount of words to print in his relatively short 46 years in essay, journalistic, and fictive forms. But this book’s snippets are loosely grouped on the single subject of telling the truth, minus all the dead elephants and talking pigs and other (often wondrous) architecture that was erected around what Orwell really wanted you to know, which is: the truth is a valuable enough thing that we should relentlessly tell it, despite our national origins or political orientations or whatever else colors our worldview.

A creature of political enthusiasms (he’d described himself as everything from a democratic socialist to a “Tory-anarchist”), Orwell didn’t let those enthusiasms get in the way of seeing clearly once he got up close and personal enough to understand the downsides of any side he initially chose. And he did get close. Sometimes, too close: whether serving as a British imperial police officer in Burma, or catching a sniper’s bullet through his throat – living to write about it – when fighting against the fascists in the Spanish Civil War. Or whether spending just as much time, if not more, bucking up against the Stalinist thugs who overtook his own side in that war, which eventually led to his great anti-totalitarian works, 1984 and Animal Farm. And which is also maybe why my late friend Christopher Hitchens (author of Why Orwell Matters) said of Orwell, he was “someone who never stopped testing and adjusting his intelligence.” As Adam Hochschild wrote in his introduction to Orwell On Truth: “As the critic Christopher Hitchens once said, Orwell personally encountered the three great malevolent movements of the twentieth century – European imperialism, fascism, and communism – and took the right stand on all three.”

Orwell On Truth leaves us with a roadmap of his hard-won insights. Which prompts me to do that thing I ordinarily hate to do – quote-bludgeoning – unless the quotes are so recommendable, they’re worth abusing the reader with. (Not for nothing do I hand copies of this book out like candy to my sons’ young friends, hoping their brains aren’t yet addled by too much dorm weed or by that Fear Factor guy’s podcast that they all seem to like.)

Here is Orwell, writing in 1941, on the consistency of intellectual inconsistency:

There are concentration camps in Germany; but then there are concentration camps in India. Jews are persecuted wherever fascism reigns; but what about the colour laws in South Africa? Intellectual honesty is a crime in any totalitarian country; but even in England it is not exactly profitable to speak and write the truth.

And here he is in the same year, writing about the wrong-headedness that often camouflages nationalistic fervor:

As I write, highly civilized human beings are flying overhead, trying to kill me. They do not feel any enmity against me as {an} individual, nor I against them. They are ‘only doing their duty,’ as the saying goes. Most of them, I have no doubt, are kind-hearted law-abiding men who would never dream of committing murder in private life. On the other hand, if one of them succeeds in blowing me to pieces with a well-placed bomb, he will never sleep any the worst for it. He is serving his country, which has the power to absolve him from evil.

Any totalitarian state, Orwell held, even ones that don’t at all think of themselves as totalitarian, all tend to operate the same way:

The peculiarity of the totalitarian state is that though it controls thought, it doesn’t fix it. It sets up unquestionable dogmas, and it alters them from day to day. It needs the dogmas, because it needs absolute obedience from its subjects, but it can’t avoid the changes, which are dictated by the needs of power politics. It declares itself infallible, and at the same time it attacks the very concept of objective truth.

This is easily done, because as Orwell wrote in “Looking Back on the Spanish War” (1943):

But what impressed me then, and has impressed me ever since, is that atrocities are believed in or disbelieved in solely on grounds of political predilection. Everyone believes in the atrocities of the enemy and disbelieves in those of his own side, without ever bothering to examine the evidence. Recently I drew up a table of atrocities during the period between 1918 and the present; there was never a year when atrocities were not occurring somewhere or other, and there was hardly a single case when the Left or the Right believed in the same stories simultaneously. And stranger yet, at any moment the situation can suddenly reverse itself and yesterday’s proved-to-the-hilt atrocity story can become a ridiculous lie, merely because the political landscape has changed.

Remind you of anything? Like everything that’s happening now? If it scares you, have no fear, it scared Orwell in his time, too. And he wasn’t just a kneejerk cynic. As he wrote: “This kind of thing is frightening to me, because it often gives me the feeling that the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world. After all, the chances are that those lies, or at any rate similar lies, will pass into history.”

From the same 1943 essay:

I know it is the fashion to say that most of recorded history is lies anyway. I am willing to believe that history is for the most part inaccurate and biased, but what is peculiar to our own age is the abandonment of the idea that history could be truthfully written. In the past people deliberately lied, or they unconsciously coloured what they wrote, or they struggled after the truth, well knowing that they must make many mistakes; but in each case they believed that ‘the facts’ existed and were more or less discoverable. And in practice there was always a considerable body of fact which would have been agreed to by almost everyone. If you look up the history of the last war in, for instance, the Encyclopedia Britannica, you will find that a respectable amount of the material is drawn from German sources. A British and a German historian would disagree deeply on many things, even on fundamentals, but there would still be that body of, as it were, neutral fact on which neither would seriously challenge the other. It is just this common basis of agreement, with its implication that human beings are all one species of animal, that totalitarianism destroys. Nazi theory indeed specifically denies that such a thing as ‘the truth’ exists. There is, for instance, no such thing as ‘science.’ There is only ‘German science’, ‘Jewish science’, etc. The implied objective of this line of thought is a nightmare world in which the Leader, or some ruling clique, controls not only the future but the past. If the Leader says of such and such an event, ‘It never happened’ – well, it never happened. If he says two and two are five – well, two and two are five. This prospect frightens me much more than bombs – and after our experiences of the last few years that is not a frivolous statement.

Subsequently, all crimes against truth or humanity become forgivable ones if committed by the right side for the right reason. As Orwell wrote in his 1945 essay, “Notes on Nationalism”:

A British Tory will defend self-determination in Europe and oppose it in India with no feeling of inconsistency. Actions are held to be good or bad, not on their own merits but according to who does them, and there is almost no kind of outrage – torture, the use of hostages, forced labour, mass deportations, imprisonment without trial, forgery, assassination, the bombing of civilians – which does not change its moral colour when it is committed by ‘our’ side…..The nationalist not only does not disapprove of atrocities committed by his own side, but has a remarkable capacity for not even hearing about them. For quite six years the English admirers of Hitler contrived not to learn of the existence of Dachau and Buchenwald. And those who are loudest in denouncing the German concentration camps are often quite unaware, or only very dimly aware, that there are also concentration camps in Russia. Huge events like the Ukraine famine of 1933, involving the deaths of millions of people, have actually escaped the attention of the majority of English Russophiles. Many English people have heard almost nothing about the extermination of German and Polish Jews during the present war. Their own antisemitism has caused this vast crime to bounce off their consciousness. In nationalist thought there are facts which are both true and untrue, known and unknown. A known fact may be so unbearable that it is habitually pushed aside and not allowed to enter into logical processes, or on the other hand it may enter into every calculation and yet never be admitted as a fact, even in one’s own mind.

I could go on and on. As Orwell did - thank God - so we have that much more of him to go on with. But ultimately, putting a stop to the incessant public lying, I suspect, comes down to something as simple as not rewarding it. For people in public life are frequently there in the first place as the beneficiaries of a spoils system – a spoils system that has become deeply, perhaps irreparably spoiled. Too many of their constituents or audiences not only tolerate being lied to, but prefer to be. Just as babies need pacifiers.

Which is why so often these days, our run-of-the-mill headlines feel purloined from Orwell’s own novelistic dystopias. As Orwell wrote in Nineteen Eighty-Four – a songbook that is cracked open so often by so many self-dealing pundits and politicians that they have ceased to hear its music, or to recognize the moral clarity that condemns what they themselves are doing:

Oceanic society rests ultimately on the belief that Big Brother is omnipotent and that the Party is infallible. But since in reality Big Brother is not omnipotent and the Party is not infallible, there is need for an unwearying, moment-to-moment flexibility in the treatment of facts. The key-word here is blackwhite. Like so many Newspeak words, this word has two mutually contradictory meanings. Applied to an opponent, it means the habit of impudently claiming that black is white, in contradiction of the plain facts. Applied to a Party member, it means a loyal willingness to say that black is white when Party discipline demands this. But it also means the ability to believe that black is white, and to forget that one has ever believed to the contrary.

I’ve read enough Orwell to think of him less as a writer than as a doctor. A doctor who might not have the cure for what’s still ailing us nearly a century after he did the bulk of his writing, but who can at least unblinkingly diagnose the disease. Which is the start of a cure if we’re ever to find one. If there’s any hope of doing so, we have to think as independently and freely as he did. For as he once wrote: “The imagination, like certain wild animals, will not breed in captivity.”

Bonus Tracks: A good lying song, The Replacements’ “Asking Me Lies.”

Though I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that’s not even my third or fourth favorite song off that 1989 Replacements album, Don’t Tell A Soul. My favorite being “Talent Show,” which is in my nighttime driving-songs hall of fame.

Politicians lie to us because we want to be lied to, demand to be lied to. Truth is a bitch. Illusion (not to say delusion) is often a much more comfortable wear.

Truth requires objective evidence. Everything else is merely belief no matter how intensely we might believe it.

In many cultures we are taught from an early age to embrace belief, to accept it as equally valid as fact. Various gods for instance, may or may not exist. Objective evidence is not to be found. And yet many of us are taught to embrace the family gods(s), virtually from the cradle. The problem is that once we blur the line between evidence and belief on one matter it becomes very much easier to blur it on any number of others, so long as the belief is for whatever reason attractive to us.

To quote the prophet Simon the Short:

"I have squandered my resistance

For a pocketful of mumbles

Such are promises

All lies and jest

Still a man hears what he wants to hear

And disregards the rest"

And so we find ourselves where are today. We vote for those who tell us what we want to hear, not for those who speak the truth. Just ask Liz Cheney.

Loved this piece almost as much as your posts on bluebirds. It connected with me on many levels, but for the sake of brevity, I'll respond with only one. When I taught high school English, I was passionate about two areas of the curriculum: grammar (yes, I was one of those English teachers) and the unit I taught on Animal Farm. I think I found that little book fascinating because it taught me so much about the nature of politics and the power of language and how it can be abused. I tried very hard to communicate these ideas to my students, not always with success. Once on a test, I asked the question: What is one major theme of Animal Farm? In spite of all the time and effort I'd put into that unit, a student, who showed greater aptitude for sports than English, wrote: To show us that animals have feelings, too. I fear my response on his paper was not one of my finer teaching moments.