By habit and preference, I spend a lot of time in the company of dogs. We tend to understand each other, as our Maslovian Hierarchies Of Need bear strong resemblance: We both like salty meat, indiscriminate naps, and being overpraised for minor accomplishments, like taking our muddy boots off before entering the house, or shaking on command.

Therefore, I spend a lot of time walking my dog. Whether at high noon or after midnight, we don’t really discriminate. We go when we feel like it. Or when I feel like it, since he always feels like it. Even when he’s in a dead sleep, and he hears my exaggerated high-pitched register, rousing, “You wanna go for a walk?!!!!” he shakes off his drowsiness, heads for the door, and does a spin or three, ever the groggy/graceful dancer anticipating our next adventure. Solomon, who is not just a good Pyrenees, but a great one, as his breed’s name suggests, spends many hours per week walking side-by-side with me in pleasing muteness. He can’t speak, and I don’t have to. I don’t know if that’s a relief to him, but it is to me. Even if he had been endowed with the gift/curse of language, and was compelled, as we humans are, to form vowels and consonants around affection that runs deeper than anything that impotent words can articulate, there’s no conversation we could have that would bind us like our companionable silence as we move through the world together.

My favorite time of year to walk him is right now – winter. Don’t get me wrong, pumpkin-spiced nerds. Fall is the most beautiful season. I have sung its hymnody in these pages. But in autumn, you’re forever reminded of fading beauty - one that can’t last, and will die any day. With winter, the death is already done. Those technicolor leaves have fallen to their graves. So the stillness and spare beauty you find feel like they will last indefinitely. When you’re attuned to nature’s cycles – and as a year-round fly fisherman and kayaker, I have no choice but to be – winter gives you an excuse to lower expectations. Stuck indoors working, you no longer feel like you’re missing out on much. But when you bundle up and venture out into the frigid world, you don’t have to register all its motion, which has mostly come to a stop. Anything that halts the world for a while – even as it seems to spin ever faster– is a hard thing to be against. Winter is a keen reminder that nature rests, even when our minds refuse to.

The other day, I took Sol-balls, as we often jokingly call him (a rescue dog, he came to us as a eunuch), for a walk in one of our favorite Maryland nature reserves. It contains my favorite kind of beauty - the kind right under your nose. Ten minutes from my house, it’s a place my family has a lot of history with. In the only populated corner of it – unpopulated this year since they weren’t able to staff lifeguards during the Great Resignation – it contains the pool that my wife and her sisters swam in as children. Along the trails that trek through miles of marshland, there are the cattails we clipped for my oldest son’s middle-school project many years ago. The Indians who once lived here used them as absorbent material in their papoose carriers. Sometimes called “Cossack Asparagus,” you could eat cattails in an emergency situation. Looking at the price of food these days, now might qualify.

At a wooden bench overlooking the sluggish Patuxent River, which features some of the most glorious sunsets in the sunset business, there used to be a notebook stashed beneath it in a Plexiglass-covered slot, where reflective types could go full Jack Handey, airing out their deep thoughts. Over a decade ago, my youngest son Dean took hold of the book, documenting his inappropriate eight-year-old observations (mostly poop and snot jokes, as I recall), amidst all the try-hard adult reflections on love and nature and beauty. The book molded over several years ago, and some soul-calloused ranger removed it. But for years afterward, I’d occasionally stop by and read Dino’s elementary-school chickenscratch – cave paintings from a world that no longer exists.

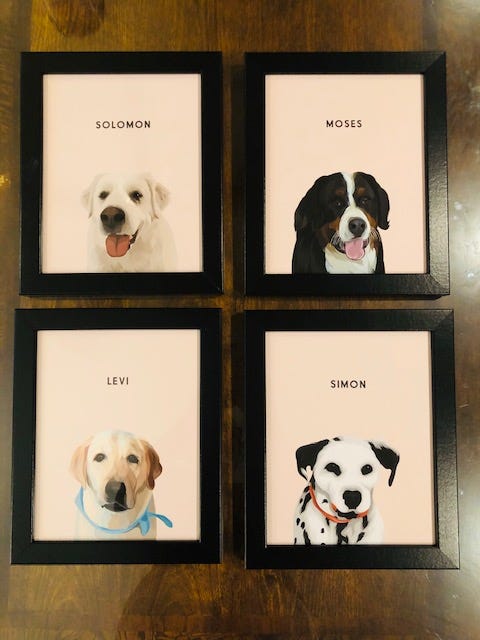

The one constant in this park is that it is the place where I walk my dogs. Not as though I have multiple dogs. When I have a dog – and I always have a dog – I am a one-dog-at-a-time man, as I don’t like dividing affection. But it’s as though each dog has passed the baton to the next, like runners in a relay who can’t last as long as I do, but who know I need one beside me on our endless walk. Simon the Dalmatian Sensation (1991-1998) giving way to Levi The Yellow Lab (1999-2008) giving way to Moses the Bernese Mountain Dog (2007-2015) giving way to the Great Pyrenees Solomon (2014-TBD). The last of whom’s original name was “General,” because his foster family found him abandoned in a Dollar General parking lot. His thick fur was matted with burrs and brambles, as he tried to nudge his way into strangers’ cars in the middle of a thunderstorm. (Solomon’s not afraid of much, but he will climb onto the couch and sit on my chest when he hears thunder – all 120 lbs of him.)

I don’t like the fact that I have to change dogs, who expire well before we do. But going dogless is not an option. And besides, as the writer Sydney Lea wrote in a collection of hunting-dog essays called Afield, when reflecting on his own dog procession:

It’s not only that I can summon grand old days with each, but I also recognize that if one of those adored dogs had in fact lived as long as I have, there’d be only the one to adore. Death is the mother of beauty, as poet Wallace Stevens famously put it, and true enough, the athleticism, the grace, the quirky personality of every one of my dogs burned themselves into my consciousness, and at length into my remembrance, not least because in my soul I understood how briefly I’d get to treasure him or her.

We renamed our dog “Solomon,” in keeping with my preference for Old Testament handles. Because just look at him in the photo that leads this piece. It’s the very photo my wife spied on a dog-finder site under a mid-sized dog category when I was looking for large ones (my favorites). Not because he isn’t a very large dog – he often gets called a polar bear by strangers - but because he was about 40 lbs underweight when we found him. I usually choose our dogs. But Alana fell so in love with his face, that she said, “If we can’t get him, I have to stop looking.” Solomon is regal and judicious, generally the portrait of calm. Unless he’s stalking the perimeter outside – she nicknamed him “Perimeter Pete” - barking at imaginary predators. (His breed was bred to guard flocks in the Pyrenees mountains. A recent Great Pyrenees story had one fighting off 11 coyotes when they threatened sheep on his Georgia farm, killing eight of them.) Or unless he’s showering affection on us. Alana couldn’t resist that mug, and I couldn’t either. Even if he had a little divot under his left eye. We don’t know what from. A thorn bush? A cigarette burn from his former owner? He’s never bothered to tell us. I like it, personally – it gives his face even more character than it already has. Still, it’s weird when you seem to be your dog’s whole world, knowing that he had a life before you: other owners, unexplained scars, a past.

But here I am now with him, on a recent gray winter’s day, walking through the woods. We pass by bat boxes and bluebird houses. Past the places where I collect fallen pine cones for kindling. Past the marshes where in warmer months, pickerel weed and arrow arum (also known as “duck corn”) bloom, and red-winged blackbirds and blue herons man their stations.

Historically, I have walked all of my dogs without a leash. But with Solomon, that’s not an option. He’s a runner. The second day I had him, and walked him leash-less, he dove off a boardwalk, ran me through mud-sucking marsh, swam across a creek, and disappeared into the woods for hours, making me think I lost him forever before he nonchalantly returned when he was good and ready. This story repeated itself a few times, until I learned my lesson, understanding that my dog-whisperer talents held no sway over him. He has a mind of his own, making it all the more rewarding when our minds meld.

As we meander through a meadow and come over a rise, Solomon leads his leash about ten feet ahead, makes a sharp right, pulls my dead weight like I’m a child’s sled, and violently dives into a stand of brush, grabbing some creature by the neck, then shaking it until it looks like that neck is snapped. I yell “no,” and pull Solomon off, as his blood’s still up, and he wants back at it. Though the possum is done for. Unless he’s just playing possum, which they’re known to do.

I have a natural affinity with most of God’s creatures, except for maybe spiders (which are creepy) and ticks (little disease factories with no personality). But I can’t say I’ve given much thought to possums, who I’ve always regarded, when I think of them at all, as albino rats - a cross between Chuck E. Cheese and Johnny Winter. Though of course, they aren’t even rodents, they’re marsupials – like kangaroos and koalas, who get much better press.

The extent of my experience with them includes watching the Possible Possum cartoon when I was a kid – featuring a dill-pickle-loving hillbilly possum who lived in a swamp, and whose catchphrase, triggered whenever other creatures asked it a question, was to say, “It’s possible.” (Pronounced in a drawl: “poss-i-boooool.”) Then there was the time I found one lying still behind my car. Figuring I must’ve clipped it, I decided to run it over, in order to make sure it wasn’t suffering. As I got out of the car and sized it up, it wasn’t suffering anymore, that’s for sure. It was as flat as rolled dough with fur. My mother-in-law, a nature-lover who has done everything from raising injured blue jays to feeding vultures in her back yard (they sometimes hop up on her patio and peck on her door if she hasn’t put out any leftovers), came up on the scene and shook her head, surveying the possum pancake. “He was probably just playing possum” she gently admonished. “Oh, crap,” I said.

But study them a bit, and they’re fascinating creatures. As the sustainability site, Treehugger, tells it, they outscore rats, rabbits, cats, and dogs when remembering where they’ve stored food. They have the equivalent of opposable thumbs. Their young often ride on their mother’s back for months. They have natural immunity to snake venom, and are incessant groomers (as in cleaning themselves, not picking up children at drag-queen story hours). They consequently eat those god-awful ticks by the hundreds, without getting Lyme disease. Anything that kills that many ticks should be a friend to both man and canine alike.

And yet, I can’t help but feel they got the shit-end-of-the-stick when God was handing out defense mechanisms. Playing dead while waiting to see if the thing that already tried to kill you finishes the job doesn’t seem like a Grade A survival strategy. As Treehugger explains it:

An opossum,when confronted with a threat, will often hiss or bare its teeth. Or more likely, run. But if it is surprised by a predator, it will enter a catatonic state. It basically faints and is in a state of unconsciousness. The opossum has no control over this; it’s involuntary. It does indeed appear {as} if the opossum is dead. Its teeth are visible, as if in a death grimace. It emits a foul substance from its anus, the smell described as corpse-like. A predator is confronted with what appears to be dead, unhealthy prey, and may leave the opossum alone. This death-feigning strategy, as some sources note, is not without its risks. The opossum is unconscious. So if the predator decides to gnaw on the opossum anyway, there’s no escape….The opossum will remain in this unconscious state for minutes to hours.

I didn’t smell any anal cologne, but the possum was wearing its death grimace. Maybe because he was playing possum, maybe because with puncture wounds and his neck twisted at an angle not seen in nature, he was actually worm bait. I ushered my bloodthirsty beast to the truck, then went back to see if there was any detectable movement, even giving the possum a poke. Nothing. If the possum was still alive, he should win an Oscar for acting, or at least a Golden Globe.

I don’t enjoy extinguishing life, neither do I take any pleasure in seeing it extinguished in front of me for no good reason. Though I spend half my life stalking animals – or at least fish – I let each and every one go. I know it’s hypocritical, but as I’ve written in fishing pieces, hypocrisy is what separates us from the animals. And even though I’m a committed meat-eater (if God didn’t want us eating mammals, he would’ve made them out of broccoli), I don’t hunt. I refuse to. Not because I wouldn’t enjoy it, but because I worry that I might. Yet the last thing I want to do when seeing a deer or a duck is to drop it in the woods or peg it out of the sky. I like to touch wildness, not snuff it out. So until they come up with catch-and-release hunting, I won’t become a member of the club.

Yet my dog is not plagued with any such reticence. We kid ourselves that they’re domesticated, yet they possess wildness, too. One night, Alana and I were watching a documentary on wolves. In the middle of it, I paused it to go out and see my own. He was up to no good. Solomon had burrowed into our yard – his nose was filthy from backhoeing – and he had retrieved a bunch of moles, which he’d proceeded to kill. With them sitting in a short stack, he was chomping them down like ladyfingers when I walked up on him. Sometimes, at his gentlest, I think the wolf in him is dead. And other times, as during the mole massacre, I realize his inner wolf is just playing possum.

When my kids were young, instead of reading them traditional children’s books, I’d fire their imaginations by reading Jack London’s Call of the Wild, the story of Buck, a St. Bernard-Scotch Shepherd mix who is stolen from his idyllic home in California’s Santa Clara Valley and sold to cruel French-Canadian dispatchers who put him to work as a sled dog in the Yukon. From there, high adventure ensues.

But I’ve always been struck by this passage when considering my own dogs:

And not only did he learn by experience, but instincts long dead became alive again. The domesticated generations fell from him. In vague ways he remembered back to the youth of the breed, to the time the wild dogs ranged in packs through the primeval forest and killed their meat as they ran it down. It was no task for him to learn to fight with cut and slash and the quick wolf snap. In this manner had fought forgotten ancestors. They quickened the old life within him, and the old tricks which they had stamped into the heredity of the breed were his tricks. They came to him without effort or discovery, as though they had been his always. And when, on the still cold nights, he pointed his nose at a star and howled long and wolflike, it was his ancestors, dead and dust, pointing nose at star and howling down through the centuries and through him. And his cadences were their cadences, the cadences which voiced their woe and what to them was the meaning of the stiffness, and the cold, and dark. Thus, as token of what a puppet thing life is, the ancient song surged through him and he came into his own again……

The night of the possum murder, my wife and I sat in front of a fire in our living room. Solomon took his post by the love seat, resting his large, smooth head on the cushion right beside me as I stroked him. He batted his white eyelashes, innocent as a baby. When I told Alana what Solomon had gotten up to that afternoon, she lightly scolded him, genuinely disappointed. “Solomon!” she said with disbelief, the same way she always disbelieves that these gentle creatures we take into our home are capable of the baby-bird’n’bunny genocides they sometimes pull off in the yard when we’re not looking. All of my dogs have tasted blood at one point or another, and they don’t seem to mind it.

Solomon took her admonition in stride, looking as regally unperturbed as ever. He nosed his muzzle under my hand after a petting pause, and threw it up in the air, as if to say, “I ain’t done yet. Keep it coming.” How could I be mad at him? I realized then and there that I love this beast not because he’s domesticated, but because at heart, he’s still wild. He tames himself for me. His behavior isn’t just instinct, but choice.

The next day, during a light drizzle, Solomon and I returned to the park/scene of the crime. He has the memory of an elephant. One time, a few years back, a fat groundhog (I called him “Phil,” after his Punxsutawney cousin), was sunning himself in the middle of a field in this same park, and we happened upon him, to his surprise. Solomon started pulling toward Phil, ready to tear him to bits. The groundhog did the calculus of how fast he could book it to the woods, and after an unsteady pause, with the help of me putting brakes on the dog, Phil made a clean getaway to his hole. For at least a year afterward, every time we came within 50 yards of that hole, and as I teased, “Where’s Phil?”, Solomon would quicken his step and furiously start sniffing the ground, reading the dog newspaper, ready to reconnect with his old pal.

On this afternoon, as we come over the same rise where Possible Possum met his untimely demise, my lumbering dog breaks into a canter. His ears perk up. His dog senses sharpen, shifting to high alert. He looks expectant. His optimism rises. He wants to see his new possum pal again. But I remind Solomon, “You offed him, Buck-o. No play date today.” But as we come up on the stand of brush, still matted from the weight of their struggle, the cadaver is gone. Maybe a fox dragged him off to the woods, or a ranger disposed of the evidence. Or maybe the possum had been playing possum all along, and he might live to see Solomon another day. I’m starting to think with dog-optimism, the best kind there is. It’s possible.

Lots of bonuses today:

Bonus Video: Speaking of dogs and bears, here’s a dog/bear video I can’t stop watching. I can’t figure out how to embed it, but it’s worth the click.

Bonus Poem: This is a poem about fathers and sons and dogs and life and death. (You know, the small stuff.) It was written by Timothy Murphy, collected in a wonderful volume called Hunter’s Log. Murphy was a longtime email correspondent of mine – he once dedicated a fishing poem to me in Gray’s Sporting Journal (one of the true honors of my life) - and he died after a short bout with bone cancer in 2018. His presence in my inbox is greatly missed. A creature of the Dakotas, he was mentored at Yale by Robert Penn Warren, and was born in Minnesota. (Bob Dylan was his childhood babysitter.) The excellent nature writer and friend of Murphy’s, Stephen Bodio, called him “not just our best hunting poet . . . he is also our bard of all things North, with the blood of the Irish and Vikings in his veins.” His poem is called “The Blind”:

Gunners a decade dead

wing through my father’s mind

as he limps out to the blind

bundled against the wind.

By some ancestral code

fathers and sons don’t break,

we each carry a load

of which we cannot speak.

Here we commit our dead

to the unyielding land

where broken windmills creak

and stricken ganders cry.

Father, the dog, and I

are learning how to die

with our feet stuck in the muck

and our eyes trained on the sky.

Bonus Track: Here’s a song I’ve listened to for years from the Boston-based band, Dispatch, filmed right in their lead singer’s living room: “Only The Wild Ones.” It starts off slow and acoustic, but stay tuned for the double-percussive show of force. It also sounds very Paul Simonesque:

"Companionable silence" pretty much says it all about my own affinity for dogs (and horses). Would probably be more open to and seek more companionship with people if they'd learn to shut their mouths a little more often.

Could go on at length about this, as you and others here well know. But so as to not have to issue a mea culpa (and God knows I owe a few), I'll shut my own now. But not before saying props on this one, Matt. Nicely done. Quite.

I loved this, Matt. It was beautiful and such a nice alternative to reading the news these days. A self-professed news junkie, I have suddenly become so sick of reading about George Santos and his pals in the House and where the latest classified docs have been found that I'm just skipping right to the Crossword Puzzle and the Spelling Bee. This piece was a breath of fresh air--kind of literally; I could almost smell the fresh air on your walk with your dog.