It’s that time of year again. No, not time to pick out my sexy Halloween costume. That’s already done. I’ve decided to forego Stripper Pirate and Pete Buttigieg in Trendy Work Boots to instead appear as Handsy Matt Schlapp. If homeowners don’t offer me a Nutty Buddy as I trick-or-treat, I’ll just grab for one, then direct them to call my attorney if they have a problem with that.

Rather, it’s birthday time. Two years ago, on this very day, I launched this thing we call Slack Tide, where our marquee subhead reads: “Taking life as it comes, not necessarily in that order.” If you’re confused, you’re not alone. I’m a little hazy on what that means, as well, and I wrote it. But it seemed like a good place-holder when my art guy was designing my logo, and he refused, out of trademark-infringement concerns, to go with my first choice: “Nationwide is on your side.”

Since I’m all about transparency, let’s speak honestly, shall we? When you get into this racket, the old Substack hands tell you that birthdays should not go unobserved. They tell you that you should use the occasion to thank paid subscribers and remind them to keep paying. To goad free subscribers into becoming paid subscribers, since your mortgage company and kids’ college accounting offices don’t accept shares and likes and view-counts as legal tender. And to beckon future readers by…..how, I’m not exactly sure. Since they’re not reading this yet. So feel free to talk smack about them amongst yourselves behind their backs, until they show up. Make them pay! A karmic toll, if not my actual subscription fee, which to kindly remind you, is $5 per month, or $50 per year (a $10-per-year savings over the monthly fee – basically, like getting two months free). If you want to change your subscription plan, this tells you how. Or you can opt in to the founder’s tier - which earns you my undying gratitude and/or a trapezius massage if you catch me in a rare personal appearance – which is $250. Though you can write in your preferred amount if you like me more than 50-dollars’-worth, but less than $250. Likewise, if you like me more than 250-bucks’-worth – say, $500 - don’t let me sell your hedonistic excess short. Better you splurge on Slack Tide than on your deadly fentanyl habit. If you look at it that way, I’m actually saving your life. Maybe it’s time to ask yourself some hard questions, like how much is your life worth?

The monthly and annual fees, I don’t mind telling you, are still among the lowest on Substack. While bad-faith price-gouging is clearly happening everywhere, I realize that your take-home pay is probably not increasing in commensurate fashion. So let’s make it easier on each other by leaving prices steady, in good faith. My ideas-supply chain has not been interrupted. No more than it usually is, anyway. (Especially during shad season.) So why punish you just because everyone else has elected to?

This is typically the part, in birthday posts, where Substack writers wax purple about the journey they’ve been on as they celebrate themselves while making lots of faux self-effacing noises about how they couldn’t have done it without their readers. Lucky for you, I respect you enough to spare you most of that ickiness. Since I promised in my inaugural essay to never use the word “journey” unless I was tracking snow leopards across the Tibetan Plateau, or discussing Steve Perry and Neal Schon getting the band back together. And since, yes, I could’ve written most of these pieces without you. Did you stay up until 2 am, banging your head against Sisyphus’s rock, looking for something new to say? You didn’t, and you shouldn’t. You have enough to worry about. Like feeding your family and hitting my subscribe button. It’s up to me to do the rest.

And what have we written over the last year? Well, plenty. If you missed it, or if you’re new, or if you’re a free subscriber who keeps risking cranial injury by running into paywalls, or if you’re a paid subscriber who is too lazy to open their emails, or if you’re a Gmail user (sadly, Gmail frequently diverts Substack offerings to their promotions folder – check yours or the archive if you’re missing pieces), what follows is a very incomplete recap of the last year.

I know that when I launched this thing, I vowed it wouldn’t merely be some axe-grinding political burn book. And it largely hasn’t been. Okay, some. Because a lot of charlatans are on the loose these days – more than ever – and occasionally need to be dealt with. With a smile and/or extreme prejudice. (It’s my country, too, and I will defend it with fangs bared, when called for.) And as everything in our entire world gets increasingly polarized and politicized, the subject of politics does arise a fair amount. So as promised from the beginning, we reserve the right to take scalps here, and take them without apology. Therefore, we took Vivek Ramasmarmy to the woodshed for being a cynical conspiracy theorist who knows better, but pretends he doesn’t - a smart guy pretending to be a dumb guy. We took on the Twidiot-in-Chief, Elon Musk, the chaos-creating Narcissus of our age, next to you-know-who. Though we handle all manner of subjects around here, we also rank in the Top Ten on Substack’s “Faith and Spirituality” leader board. So in that spirit, we considered whether Jesus was woke. As a good Christian, or at least a lukewarm one, I tried to remind readers – in what ended up being my most highly-viewed piece of all-time - that Donald J. Trump was not Jesus H. Christ – no matter how many people have turned politics into their religion, and no matter what a recent book claimed about Trump being the literal Mango Messiah.

There were plenty more political essays (this is not a complete list) on every subject from the importance of distrusting your own side, to the Duhhh-Santis fizzle, to the January 6 Prison Choir committing crimes against music and their country, to me shadowing my former brother-in-law in a local election, as he tried to sort out what it means to be an honest politician in a climate of rampant dishonesty.

But there was much, much more. Because as also initially promised, we try to measure life in its entirety – the Big Ball Of Everything, I call it. Show me a man who is only defined by his politics, and I will show you one not worth knowing. The world is a lot bigger – thank God! – than our small-minded politics would suggest. And so here is a tasting menu of some of my near-and-dear subjects, with one-paragraph excerpts from each.

Last October, I offered a Neo-Luddite’s Lament:

…..Thoreau had it about right when he observed that “men have become the tools of their tools.” Tools which, after some great technological leaps forward, have largely stalled in the genuine innovation department, while still yielding up an endless array of elective contrivances. These are tools that we kid ourselves into thinking allow us to ingest life as quickly as possible, while practically guaranteeing that we don’t truly taste much of it. Our own lives are now often reduced to naked exhibitionism or vicarious voyeurism on Facebook and Instagram. I’m liked, therefore I am.

We tackled the nagging temptation of trying too hard to be young, when we’re not all that young anymore, in the form of Martha Stewart serving as cover-girl for the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue:

Martha Stewart is still a very attractive woman who looks better than all of the aforementioned. (Except maybe for Ronald Isley – because “black don’t crack” as my esthetician friends like to say.) And I don’t say any of this to age-shame. Quite the opposite. There is something wondrous and beautiful about aging. And it’s not about being wily enough to fool young people into thinking you’re one of them. Trust me, you’re not fooling anyone if you’re attempting that, except yourself. As a fiftysomething man, this is why I don’t wear “skinny” suit pants, cut four inches above my ankle, as an expression of my individuality, which would actually just be an expression of conformity – trying to fit in with people who won’t think of me as one of them no matter how hard I try.

And we tackled aging once more when I went to the Amalfi Coast for a wedding with my family, and found myself not only writing about Italy – the world’s most glorious country. But also caring for my rapidly-aging, once-robust father-in-law – now often hauling around an oxygen tank - after a comedy-of-errors that saw us slogging our way through cancelled flights, health travails, and all-around general travel hell. A trip in which I was just relieved to get him back alive:

I’ve always liked to picture Vic on the move. A man of the world. A man of action. The man who fixes things around my house when I can’t. The man who gave me my wife, who herself gave me my life, not to mention my children. Though after our endurance test, I’ve become quite all right with picturing him as a man of inaction. By necessity, if not by choice. We ride him back from Dulles, and deposit him in his easy chair in Southern Maryland. We all feel relief. He seems nearly energized by the prospect of returning to his old routine. He can now get back to triangulating the news between Fox-CNN-MSNBC, in order for him to figure out who is lying about what. He is breathing easier. Back to watching the world collapse virtually, instead of having it collapse physically around him in real time, in 95 degree heat, with steep walks that his lungs can no longer make.

But we don’t just cover negativity, here. Why does your own personal Substack exist, if not to inflict your enthusiasms on others? And I have a lot of those. Here is me covering the glories of brook trout fishing through bad-news Armageddon with my youngest son, Dean:

I’m a competitive fisherman – which is why I usually prefer to fish alone, to mute that tendency in myself – but I can’t help but be overjoyed when I fish with my sons, and they succeed, even when I don’t. Since their success is mine, too. Watching them get a piece of what brings me peace…….well, only a monster could begrudge that. As Dean and I adjourn for Mexican food afterwards, I look at this “kid,” who just a few years ago, I was double-knotting his wading boots and clinch-knotting his flies so they didn’t come off when the branches ate them, and he now has a full beard, and employs words like “nihilistic” correctly, and he downs a tall Modelo draft over enchiladas before I’m halfway done with mine. And he outfished me 7-to-1. And I somehow feel complete. Like I have something more important than a son. I have a fishing buddy for life, who will know when and how the world needs escaping, the same as I do.

Or there’s the glorious screwball short films of a Scandinavian jazz-playing/fly fishing troupe, called Jazz & Fly Fishing, that I’ve been watching for over a decade:

And of course, northern Scandinavia (they are often fishing above the Arctic Circle) is itself a character in their shorts. I’m not necessarily a Scandinavian fetishist – I can do without their exorbitant tax rates, their pickled fish, and their Norwegian death metal. Even though I love Viking shows, Northern Lights, Swedish meatballs, hot saunas, and Ingrid Bergman. (Taking a sauna with Ingrid Bergman in a horned Viking helmet, feeding me Swedish meatballs, would pretty much be an ideal afternoon.) But the landscapes in their films are utterly beautiful, possessing that peculiar Nordic mix of lush barrenness, with the light adjusted just right – luminousness with the shades drawn. It’s the kind of light the Swedish artist Carl Larsson called “a painter's dream, it transforms the ordinary into the extraordinary." Or what the Nobel laureate writer, Par Lagerkvist, described as possessing “a tender quality, it embraces the landscape and whispers secrets to the trees and the seas."

Or there’s my musical heroes, like The Band, which I took 9,000-word stock of on the occasion of Robbie Robertson’s recent death:

The musically-nimble Beatle knew what anyone with ears to hear could readily spot: that this remarkable ensemble served up a strangeness that was utterly familiar. Much like the British Invasion played our blues back to us, making it new, The Band – four Canadians (Robertson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson) and a yowling, spitfire drummer who grew up on a cotton farm in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas (Levon Helm), took a raw-ingredients pinch from every slot of our rootsy spice rack: from delta blues to Staple-Singers-style gospel to high-lonesome country to Motor-City soul to Appalachian front-porch string bands to Sacred Harp singing to Louisiana swamp rock to a good ten other influences I’ve forgotten or failed to name. They dumped it all in the stockpot, blended it, and cooked up their own unwritten recipe (none of them besides their organ-genius Garth - who honed his chops playing his uncle’s funeral parlor, and who used to charge the rest of The Band for music lessons in their early days - could even read music). They made us feel like we were hearing old songs that we’d temporarily forgotten, sung by longtime friends we’d just met, helping us to recall what makes us, us. Or, as Bruce Springsteen once put it: “Here come all these voices that sound like you’ve never heard them before, and they’ve always been there forever and ever.” At their best, The Band played something like ancient hymns that don’t change shape with time, but reverberate throughout it. Some say that the best writing reminds us of what we already know, but haven’t yet articulated to ourselves. That was The Band in a nut. Except they didn’t just articulate words. They set America to music, the purest language that exists. Music being the world where words alone peter out, and something otherworldly takes over.

Or there’s my literary heroes, of which there are not too many, but just enough. Like George Orwell, who tells us how not to lie:

I’ve read enough Orwell to think of him less as a writer than as a doctor. A doctor who might not have the cure for what’s still ailing us nearly a century after he did the bulk of his writing, but who can at least unblinkingly diagnose the disease. Which is the start of a cure if we’re ever to find one. If there’s any hope of doing so, we have to think as independently and freely as he did. For as he once wrote: “The imagination, like certain wild animals, will not breed in captivity.”

Or Wendell Berry, who instructs us how to hate less:

Calling out such hypocrisy across-the-board as our tribes have grown increasingly tribal can get you accused of bothsidesism or worse by the kind of people who employ Twitter neologisms to foreclose real conversation instead of actually participating in one. Which is why Berry generally resists “movements,” as those too often require binary answers, either/or’s. “It may be that actual thought about a problem requires more than two opinions,” Berry writes. Failing to succumb to the New Dumbness that has become our discourse, such as it is – with the language gazpacho often policing what we can or can’t say instead of us having free reign to explore any idea - is why Berry often feels anachronistic. Besides, having fled the spoils of blue-chip academe and literary-lionhood early in his life to return to an existence as a humble Kentucky farmer, even as humble farmers were getting planted six feet under by corporate bigfoots, Berry has never had an aversion to swimming against the current. As he told The New Yorker in a sprawling profile last year: “I seem to have been born with an aptitude for a way of life that was doomed.”

Or here’s one of my very favorites, the great Jim Harrison, who instructs us how to live, generally-speaking, in a piece I wrote last February titled “Holy Books”:

We tend to love the people who love (and hate) the same things we do. And in that department, Harrison ticked most of my boxes: he loved dogs and birds, walking through woods and fly fishing the rivers that run through them. He had large appetites. He loved food, perhaps too much. (He once wrote a piece for The New Yorker in which he consumed a 37-course, 11-hour meal in a restaurant in Burgundy, which, as a professional poet, he did not pick up the tab for.) He thought the cure for every ill was more red wine and fresh garlic. (Not in the same glass.) He loved words, and writers who weren’t afraid to use them in full-bodied fashion. While he appreciated Hemingway’s craft, he once regarded him as “a wood stove that doesn’t give off much heat.” Give him writers whose offerings had stronger circulatory systems: Rimbaud and Lorca and Henry Miller, the last of whom Harrison said “saved my neck” when he was young, by offering “more abundance – mental heat, experience, jubilance.”

I was exaggerating when I called Harrison’s output “holy books,” but then, of course, there are the things that are holy themselves, like dogs and nature and wildness, which I discussed at some length when contemplating my Great Pyrenees, Solomon, who’d just killed a possum on one of our rambles, in a piece titled “Winter Walk With A Stone-Cold Killer”:

The night of the possum murder, my wife and I sat in front of a fire in our living room. Solomon took his post by the love seat, resting his large, smooth head on the cushion right beside me as I stroked him. He batted his white eyelashes, innocent as a baby. When I told Alana what Solomon had gotten up to that afternoon, she lightly scolded him, genuinely disappointed. “Solomon!” she said with disbelief, the same way she always disbelieves that these gentle creatures we take into our home are capable of the baby-bird’n’bunny genocides they sometimes pull off in the yard when we’re not looking. All of my dogs have tasted blood at one point or another, and they don’t seem to mind it. Solomon took her admonition in stride, looking as regally unperturbed as ever. He nosed his muzzle under my hand after a petting pause, and threw it up in the air, as if to say, “I ain’t done yet. Keep it coming.” How could I be mad at him? I realized then and there that I love this beast not because he’s domesticated, but because at heart, he’s still wild. He tames himself for me. His behavior isn’t just instinct, but choice.

That’s some of what we did here in the last year. And so I hope if you’re with us, you’ll stick. And if you’re not, that you’ll come to think of this place as somewhere you want to loiter, too. For while I earlier made sport of Substack writers who praise their readers, that was disingenuous on my part. Because I can’t praise mine enough. They’ve restored my faith, in some ways. Not only have they proved thoughtful, reasonable, and generous – characteristics which aren’t in abundant supply nowadays on the internet. But they demonstrate how to be so regularly in our comments section, which I wall off to paid subscribers, to make sure it stays civilized. (Trolls don’t often pay for the privilege of trolling, and if they do, I bounce them anyway.) Though I’ve always been opposed to comments sections – as I’ve written before, I wouldn’t typically go near one without a rabies shot – our comments section here is a place where I frequently jump in and mix it up with commenters, even when they disagree with me, which they often do. But they do so with grace and respect, for the most part. You can’t have too much of either when dealing with intimate strangers.

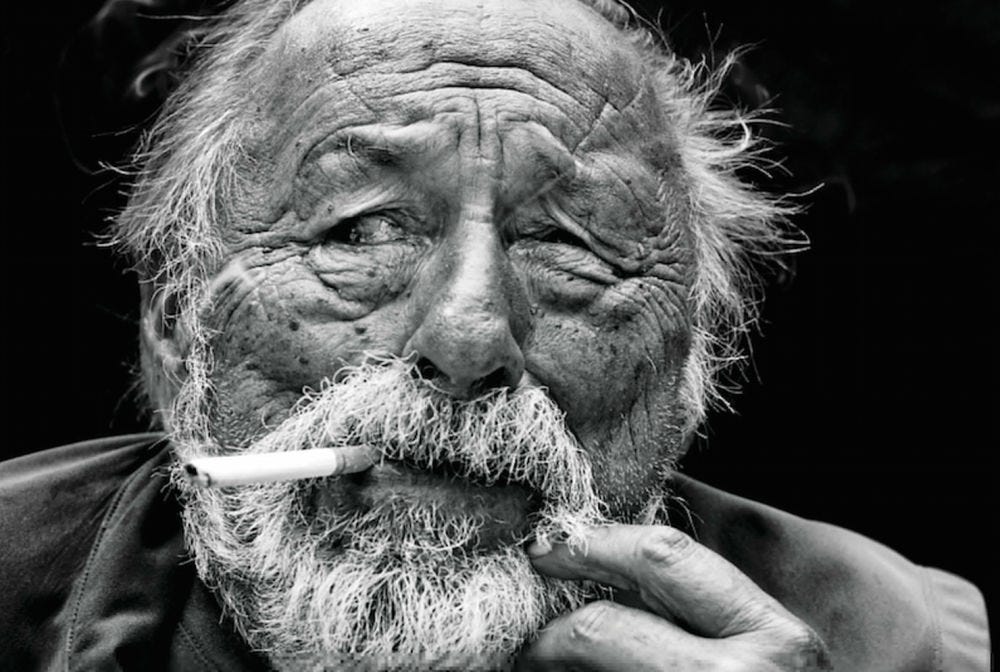

I have even written about said readers numerous times. Including, last November, after a hardened atheist named Tom Missler, who joined our Slack Tide band, quarreled with me over God, even as he was about to meet his Maker (in my book), or to meet the void (in his). Tom joined up when he was already near death, with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He asked me if he could buy a six-month subscription, since he figured he didn’t have long. And he didn’t. We tussled a decent amount, good-naturedly – I catalogued our tussle in a piece called “Doubting Thomas,” in the summer of 2022. Then we moved on to other important things. Like life itself - what we had in common - until he left his life behind. Which he did, last fall. Around Thanksgiving, I wrote a second long piece about him after he died, titled “Enjoy Every Sandwich,” which shared double-billing with the late, great singer Warren Zevon (coiner of the headline I used), who Tom reminded me of in all kinds of ways. Me, giving thanks to the God Tom didn’t believe in for enriching my life with such a magical, mystical stranger such as him:

I started calling Tom “The Ice Cream Man.” I’d mentioned his favorite ice cream in “Doubting Thomas,” one of the small pleasures he was always on the hunt for as his body was irretrievably breaking down. Specifically, the Black Raspberry Chocolate Chip made by Graeter’s, the ice cream company that is the pride of Cincinnati. After the piece was published, Tom asked me for my address without specifying why. I thought he might send me a book or something. He was always forwarding articles he found interesting, on every subject from why fog was disappearing in the Bay Area, to the latest misadventures of Trump, who Tom disparagingly called “the ferret wearer” to his MAGA-inclined relatives. He never stopped being interested in the world that he still inhabited. But a week or so after his address inquiry, a large Styrofoam cooler packed with dry ice and about a dozen pints of Graeter’s Black Raspberry arrived on my doorstep. It had to set this dying man in hospice back a good 150 bucks. He could’ve spent it on a new driver, which he’d need if he could gain enough lung power back to swing a golf club. (A fantasy he repeatedly voiced, that was not to be.) “I can now watch golf and think about my swing in my head,” he wrote. “Not as much fun as standing in a trout stream, but one day that will be a memory for you.”

Tom, for me, didn’t just become an instant old friend, but became one of the weird life turns I treasure. Because if you’re open, life always takes some of those. Years ago, well before the magazine I worked for for 23 ½ years was murdered by its owners, my wife, who is sometimes subject to prophetic insights, told me, “I think a change is gonna come. You’re still going to write. But you’re going to be writing about things like politics and God and fly fishing and music.” I thought she was drunk, even if I like to do most of the drinking around these parts. That would be a great job, I told her, if it existed. But it doesn’t. I patted her on the head, and thanked her for her fantastical visions, while quietly thinking she was crazy, then going about my business. I hadn’t even heard of Substack yet, probably because it didn’t exist. But now, I find myself writing about all those things – sometimes in the very same piece. Which is nothing I ever expected. Maybe that’s what grace looks like up close. When things come to us that are better than what we deserve.

And you make that possible. (Not to flatter you.)

So thank God life takes weird turns that we don’t always initially want and can’t always anticipate. Here’s hoping others will take those turns with us. (Don’t be shy about conscripting your friends and relatives.) For you being here, and reading this, and helping me discover new ways to do this thing I’ve done my entire adult life, I extend my genuine thanks, as we head into our Terrible Twos. And I have but one simple request: be more like Tom. If you try a little harder, I might get a few pieces out of you, too. The empty page is a hungry one that forever needs fed.

Bonus Track(s): I don’t have a good birthday song. So I’ll just play one that makes me happy whenever I hear it. Jack Johnson and the wonderfully soulful Hawaiian singer Paula Fuga doing “Better Together.”

And since my wife name-checked Sam Cooke’s song upstairs, let’s work that in, too. So you can understand what a truly brilliant singer Cooke was, here’s an isolated vocal – no instrumentation - of “A Change Is Gonna Come.”

I missed your 23 1/2 year stint at your last gig and didn’t stumble on your writing until it was referred to by Bill Kristol in some tweet or other, I think in 2022 sometime. The Substack model reminds me of streaming to some extent: there are a million people whose work I’d like to read but they’re all on different “streaming services” that you have to pay separately for. So I have to pick my spots for which Substacks I’ll subscribe to and pay for and which ones I’ll view with my nose pressed against the window. Yours is one of the former, as I very much appreciate your writing. I hope you enjoy many more years of success with Slack Tide - I promise to keep reading if you keep writing.

To freeriders:

I've written and talked about Matt L. Tide to friends and relatives. I read his stuff aloud to my wife every week. His writing is never vicious or acrimonious, but he can give a thousand paper cuts to those that deserve an ole fashioned butt whoopin'. Like he said, he shares observations about fishing, dogs, music, religion (sort of), an Italian crazy vacation with a loving bow to his kith and kin and they are are brilliant. The variety of ageless music, at the end of each, is always there.

It's not healthy to envy others. It's best to "Be Thankful for What You Got," https://youtu.be/Pvtlt-p7vB4?si=3U-lh6L45toMxBb7

But if I could have a super power, other than throwing a MLB no-hitter, I'd be over the moon if I could write like Matt. Laugh, cry, smile, and not end up feeling like we're at the end of things is worth the price of admission. I wish I could compare him to other authors, but I can't. He is a mad, brilliant, clear eyed, romantic who loves the weirdest of us. The weirder the better. Many people write. Matt composes.

https://youtu.be/-W8Jdh9vjtQ?si=-zSErXwG2Gm5X7-q